Perched atop the gigantic granite boulders that form the backbone of Montague Island the lighthouse has stood watch over the treacherous waters of the Tasman Sea for almost 150 years.

The island, 9km off the coast from Narooma, was known to the Yuin people as Barunguba and deeply connected to their Dreaming as the “eldest son” of Gulaga (Mount Dromedary), was first spotted by European eyes when Captain James Cook sighted it in 1770, mistaking it for mainland and naming it “Cape Dromedary.” It wasn’t until 1790 that a master of one of the Second Fleet’s convict ships recognized it as an island and renamed it “Montagu” after George Montagu Dunk, Earl of Halifax.

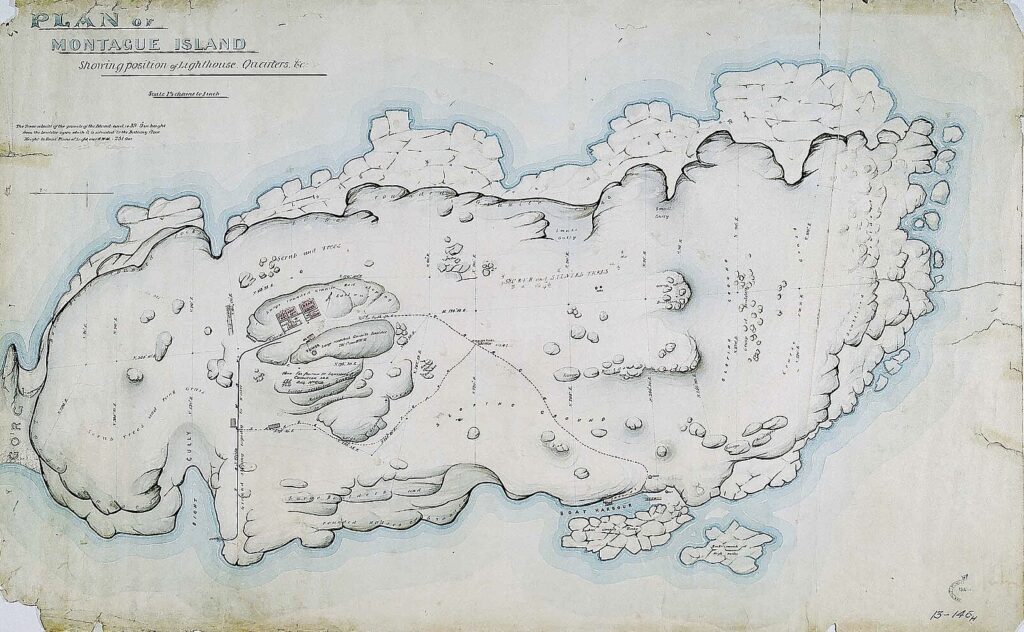

As shipping traffic increased along New South Wales’s south coast in the 19th century, so did the tragic toll of shipwrecks. Recognising the urgent need to improve navigation in these dangerous waters the NSW government commissioned Colonial Architect James Barnet to design and oversee the construction of a lighthouse on Montague Island. This was to be the second of fourteen lighthouses along the NSW cost to bear his distinctive architectural style, perfectly balancing aesthetics with functionality.

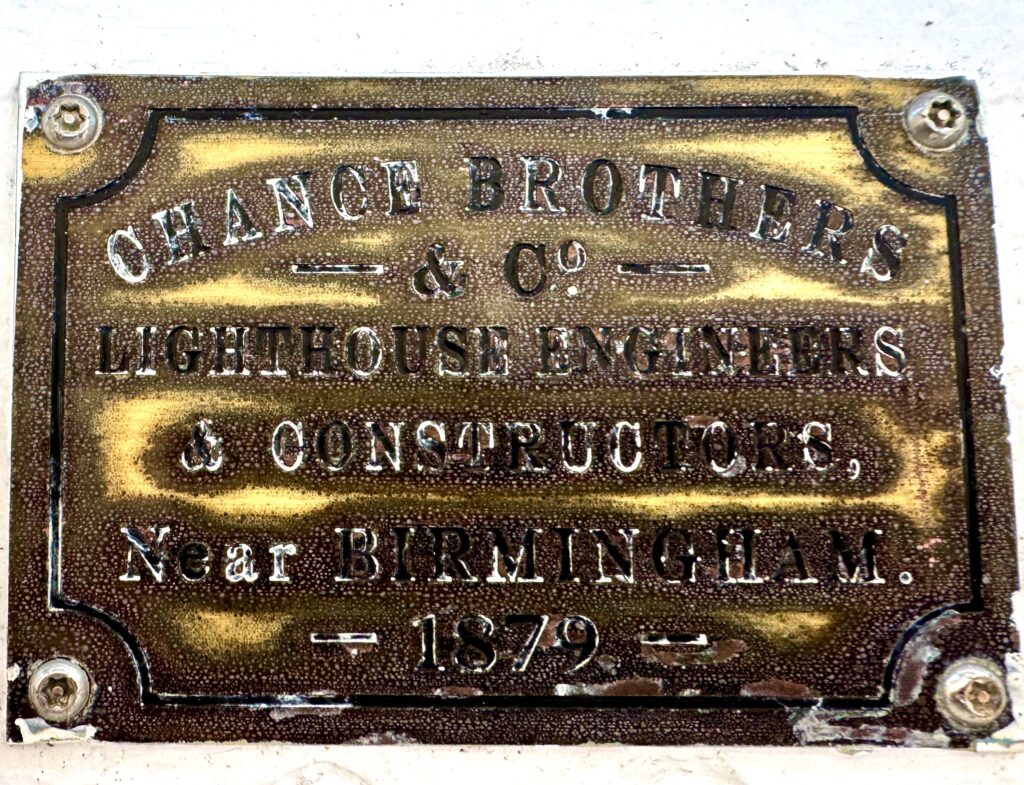

Constructed from granite quarried directly from the island—the same material Barnet used in other colonial landmarks including Sydney’s GPO—the tower stands 12 meters tall. Positioned strategically at the island’s highest point, the light beams from 80 meters above sea level. Completed in 1881 at a cost of £7,000 which, in those days, was regarded as a major investment by the colony in its maritime safety.

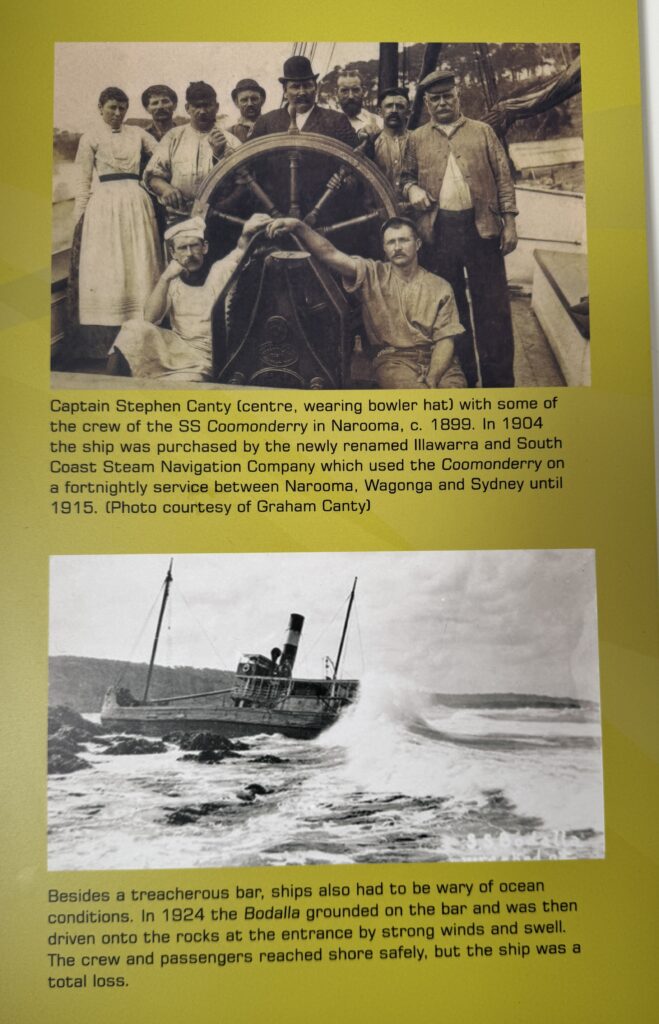

The lighthouse came too late for the ill-fated Lady Darling, a 400-ton steamer that ran aground and was wrecked on a nearby reef off Mystery Bay in 1880, just months before the lighthouse’s operation. While the lighthouse’s presence significantly reduced maritime disasters the sea continued to take its toll including the steamer Bega sank in 1907 during a fierce gale near Tathra, 50 km to the south, claiming 63 lives from its 73 passengers and crew.

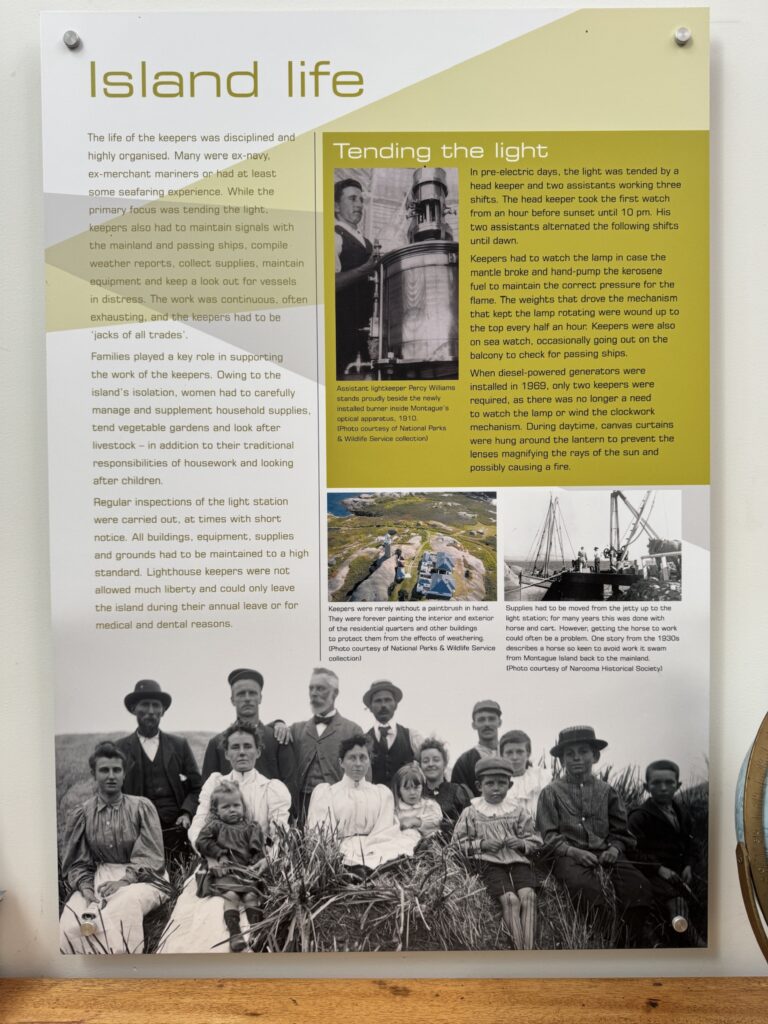

Life for the lighthouse keepers and their families embodied isolation in its purest form. The head keeper and two assistants maintained the light and lived on the island with their families, their only communication with the mainland through signal flags. Supply ships visited merely twice a year, forcing a life of self-sufficiency. The keepers grew vegetables, fished the surrounding waters, and introduced domestic animals for food and as work horses. This intervention, however well-intentioned, unleashed an ecological catastrophe as rats, mice, rabbits, and goats multiplied unchecked, devastating the island’s native vegetation and wildlife.

For 106 years, keepers maintained their lonely vigil until automation arrived in 1987. Management transferred to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, marking the beginning of environmental restoration. Through dedicated conservation efforts, all non-native animals have been eradicated, native flora replanted, and the island once again teems with migratory seabirds, little penguins, and fur seals. Today, Montague Island stands protected as a nature reserve with stringent biosecurity measures and controlled access.

Like many remote lighthouses, Montague holds its share of mysteries and sorrows. Yuin oral tradition speaks of a devastating tragedy when 150 people perished in a sudden squall while attempting to cross to the mainland in bark canoes centuries ago. During storms, some locals claim to glimpse unexplained lights or shapes offshore, attributed to these lost souls.

A small, poignant cemetery near the lighthouse tells its own tales of isolation’s cruel cost. Assistant Keeper Charles Townsend rests there after dying from a horse kick to the head in the 1880s. Nearby lie two children of Head Keeper James Burgess—little John, just two years old, and Isabella, aged four, who succumbed to meningitis in 1888 and 1894 respectively. Rough seas prevented medical help from reaching them, forcing their heartbroken parents to bury them on the island.

The waters surrounding Montague continue to claim lives occasionally. In the 1970s, a tourist boat capsized nearby, killing two people, and maritime emergencies remain a regular occurrence in these waters.

Among the lighthouse’s more peculiar legends are tales of horses that despised island life, becoming notoriously ill-tempered—as poor Charles Townsend discovered fatally. One determined horse reportedly escaped and swam through shark-infested waters to the mainland not once but twice. Another curious horse-related myth involves a horse skeleton and debris from the Yongala, which sank near Townsville in 1911, washing ashore on Montague Island three years after the vessel’s disappearance.

A more recent mystery relates to the apparent loss of the original Fresnel lens which was removed in 1986, but which went missing without trace until 1990 when it reappeared in pride of place at the newly constructed Narooma Lighthouse Museum.

Now heritage-listed and maintained by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, the Montague Island Lighthouse continues its watch while NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service keep watch over the island, its natural beauty and historical significance preserved for future generations as a testament to Australia’s maritime heritage.