For me Point Perpendicular has always had a special place in my heart. This goes back to the fact that when my mother was a young girl her family had a holiday house at Huskisson and she told me how she use to go to sleep at night comforted by the flashing light at the edge of the World (very similar to my childhood recollections of Barrenjoey and possibly the origin of my own lighthouse fascination).

Apart from this family connection it’s easy to understand why this lighthouse has such universal appeal, perched atop precipitous sandstone cliffs it guards entrance to Jervis Bay one of the deepest natural harbors on Australia’s eastern seaboard. Point Perpendicular has guided mariners through these challenging waters since 1899, its powerful beam visible from over 26 nautical miles at sea.

The dramatic headland upon which the lighthouse stands holds deep significance for the Jerrinja people of the Dharawal nation, who knew this place as “Beecroft” and for generations they maintained a deep connection to these lands and waters predating European arrival by millennia.

The strategic importance of Jervis Bay was recognised soon after European settlement began in Australia. The bay was first charted by Lieutenant Richard Bowen in 1791 and subsequently named after Admiral Sir John Jervis by Matthew Flinders. As colonial shipping increased along the coast, the treacherous entrance to this otherwise sheltered harbor claimed numerous victims. The jagged rocks and unpredictable currents around Point Perpendicular proved particularly hazardous during storms or poor visibility.

and the Tasman Sea on the other

Among the most tragic shipwrecks was the loss of the passenger steamer Wandra in 1870, which struck rocks near the point during a thick fog. Of the 83 souls aboard, only 14 survived the initial impact and freezing waters. The absence of any navigational aid to warn of the approaching headland was cited as a contributing factor in the subsequent marine inquiry, adding weight to growing calls for a lighthouse at this perilous location.

Despite the clear need, bureaucratic delays meant it would be nearly three decades before construction began. The catalyst came in 1895 when the Walter Hood, a three-masted iron clipper returning from London laden with valuable cargo, was dashed against rocks near Beecroft Head during a violent storm. Of the 24 crew members, only 9 survived, and the ship’s cargo, which ironically included components for another lighthouse being built further north were lot to the deep.

This disaster finally prompted colonial authorities to commission a lighthouse for Point Perpendicular. The design fell to James Barnet’s successor as Colonial Architect, Charles Assinder Harding, who conceived a structure that married function with elegant simplicity. Unlike earlier stone lighthouses along the New South Wales coast, Point Perpendicular marked a transition to more modern construction techniques, built from concrete blocks made on-site using local sand mixed with imported cement.

Construction commenced in 1898 and was completed in 1899 at a cost of £13,550, the light stands 93 meters above sea level thanks to its commanding position atop the cliffs, making it one of the highest in Australia in terms of focal plane elevation.

The lighthouse was equipped with a first-order Chance Brothers dioptric lens assembly—the largest and most powerful category of lighthouse optics. This magnificent piece of precision engineering, comprising hundreds of hand-ground glass prisms arranged in concentric rings, concentrated light from an incandescent kerosene vapor lamp into a beam of exceptional intensity. The distinctive light characteristic—one white flash every 10 seconds—soon became familiar to generations of seafarers navigating these waters.

Life for the three keepers and their families assigned to Point Perpendicular embodied isolation in its purest form. The lighthouse station, though not as remote as some, remained cut off from civilization by the rugged terrain of Beecroft Peninsula. A rough track provided the only land access, becoming virtually impassable during heavy rains. Supplies arrived by sea every three months, weather permitting, and were hauled up the steep cliff face on a flying fox—a precarious operation even in calm conditions.

The keeper’s cottages, constructed from the same concrete blocks as the tower, provided sturdy if basic accommodation. Each family maintained vegetable gardens and kept livestock to supplement the limited provisions delivered by the supply vessel. Children received education through correspondence courses, with the head keeper often serving as de facto teacher. Medical emergencies presented particular challenges, with several lighthouse children born with only the assistance of other keepers’ wives.

Harold Boulton, who served as head keeper from 1911 to 1923, recorded in his journals the profound psychological impact of this isolation. During one particularly fierce winter storm season in 1912, which prevented supply vessels from approaching for nearly five months, Boulton noted how his assistant keeper’s wife became convinced the rest of humanity had perished in some cataclysm, leaving them as the sole survivors. This episode of what would now be recognized as situational psychosis passed once contact with the outside world resumed, but illustrated the mental toll such isolation could take.

The lighthouse witnessed the full fury of nature on countless occasions. Perhaps most dramatic was the “Great Gale” of July 1937, when hurricane-force winds lashed the headland for three consecutive days. Keeper Samuel Jenkins recorded how sea spray was thrown completely over the lighthouse tower—an astonishing feat considering its elevation—while windows in the keeper’s cottages imploded from the sheer atmospheric pressure differential. Throughout this meteorological onslaught, the keepers maintained the light, climbing the tower every three hours to wind the clockwork mechanism that rotated the optical apparatus.

World War II brought strategic significance to the lighthouse and its surrounding peninsula. With Jervis Bay considered a potential target for Japanese naval forces, the lighthouse station was placed under military authority. Blackout restrictions severely limited the light’s operation, and keepers received training in coastal observation techniques. A radar station was established nearby, and gun emplacements constructed along the headland—concrete remnants of which can still be seen today.

By the post-war period, technological advances began transforming lighthouse operations nationwide. In 1964, Point Perpendicular was converted from kerosene to electric power, though keepers remained essential for maintenance and monitoring. The final chapter in manned operation came in 1993, when full automation eliminated the need for resident keepers, ending nearly a century of continuous human presence.

In an unusual twist of fate, the lighthouse precinct was subsequently transferred to the Department of Defence as part of the adjacent Beecroft Weapons Range, limiting public access to the site except on designated open days. This restriction has inadvertently helped preserve the lighthouse station in near-original condition, protected from vandalism and inappropriate development.

Like many remote outposts, Point Perpendicular has accumulated its share of mysteries and legends. Persistent tales speak of unexplained light phenomena within the tower during electrical storms—corona discharges described by some witnesses as resembling human figures. These manifestations, attributed by more superstitious observers to the spirits of those lost in nearby shipwrecks, likely result from the natural electrical properties of the isolated tower during atmospheric disturbances.

More tangible is the curious case of the “Perpendicular Diary,” a leather-bound journal discovered concealed within the lighthouse wall during renovations in 1982. The journal, apparently maintained secretly by an assistant keeper from 1902 to 1904, contained detailed observations of unusual marine activity in Jervis Bay, including what the writer believed to be a previously undocumented species of large marine mammal. Marine biologists who examined the journal suggested the keeper had likely observed orcas, uncommon but not unknown in these waters, though some entries describe behaviors not typically associated with any known cetacean species.

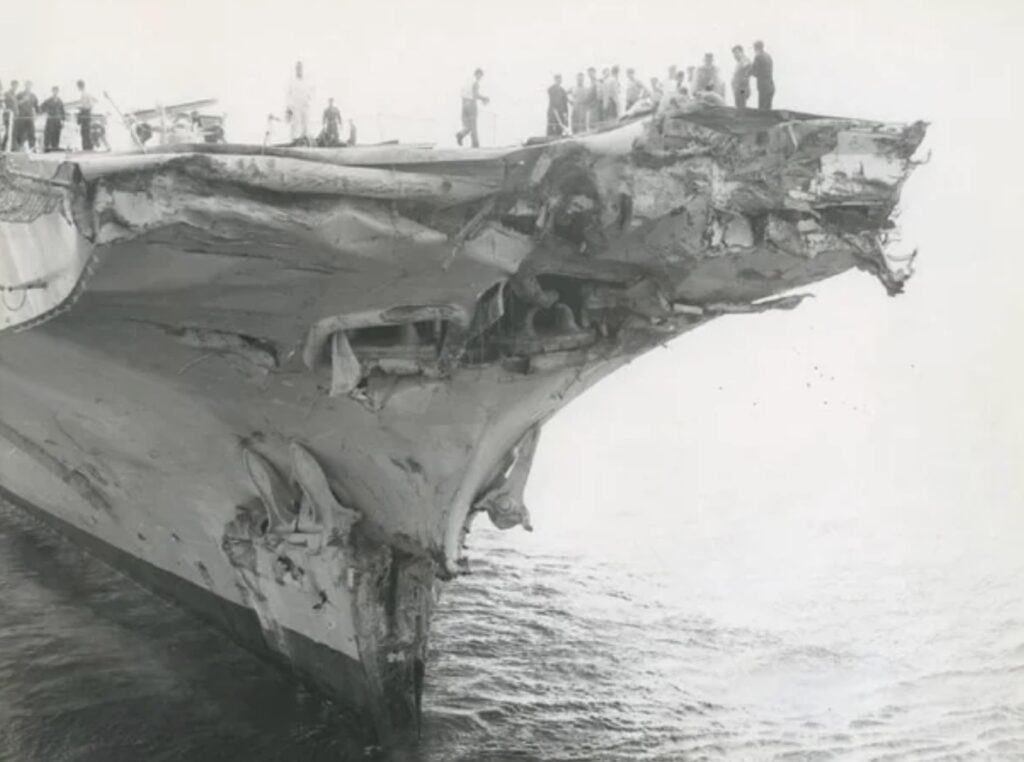

Point Perpendicular has witnessed many maritime emergencies and accidents but none as devastating as the Voyager disaster. This was the worst peacetime loss of life for the Royal Australian Navy and occurred on February 10, 1964, when the destroyer HMAS Voyager was sliced in two by the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne during a routine night exercise. The collision, which killed 82 sailors, happened when Voyager was acting as a plane guard for Melbourne, and a misinterpretation of maneuvers or a communication error likely led to the tragic accident.

The waters surrounding Point Perpendicular continue to claim victims occasionally. In 1973, a pleasure craft with seven aboard disappeared without trace near the headland during seemingly moderate conditions. Despite an extensive search, no wreckage was ever recovered, adding to the peninsula’s reputation for maritime mystery. More recently, in 2008, two rock fishermen were swept from the cliffs below the lighthouse during a sudden swell, highlighting the continuing dangers of this spectacular but treacherous coastline.

Today, the lighthouse stands heritage-listed and maintained by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority as an active aid to navigation, though its importance for maritime safety has diminished in the era of GPS and electronic navigation. The original Chance Brothers lens, removed during automation, has been preserved and placed on display at the Lady Denman Maritime Museum in Huskisson, where visitors can admire the incredible craftsmanship of this 19th-century optical marvel.

On the occasions when Defence Department operations permit public access to Beecroft Peninsula, the Point Perpendicular Lighthouse draws visitors eager to experience its dramatic setting and historical significance. Standing at the edge of the towering cliffs, with the lighthouse gleaming in the sunshine against the deep blue of the Tasman Sea, one gains a profound appreciation for the generations of keepers who maintained this beacon through isolation, storms, and war—a testament to Australia’s rich maritime heritage preserved at the edge of the continent.