Overlooking the picturesque coastline of Wollongong two distinctive lighthouses stand guard to the entrance to the harbour, the stately Wollongong Head Lighthouse commanding the heights of Flagstaff Hill, and its older companion, the charming hexagonal Wollongong Breakwater Lighthouse marking the harbour entrance. Together, these maritime beacons have guided vessels safely through treacherous waters for generations.

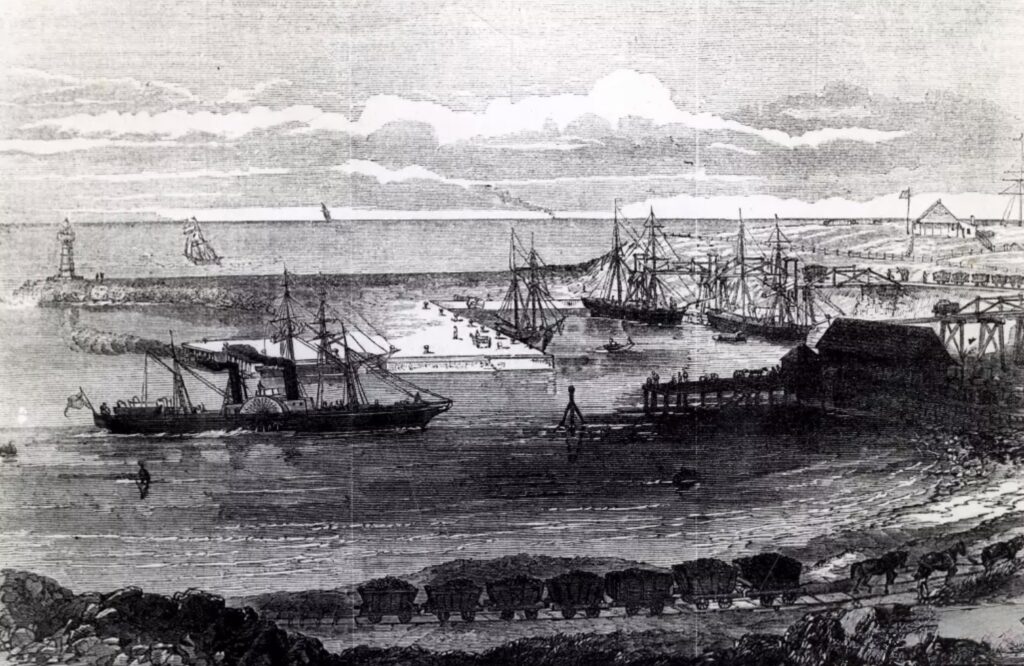

The Wollongong region was known to the Dharawal people as “Woolyungah,” meaning “five islands,” referring to the rocky outcrops visible from the shore. European settlement brought increased maritime traffic to the area, particularly as coal mining boomed in the Illawarra in the mid-19th century. As ships increasingly navigated these waters, the need for reliable navigational aids became painfully apparent through a series of tragic shipwrecks along this rugged coastline.

Responding to these maritime disasters, the colonial government commissioned the Wollongong Breakwater Lighthouse in 1871. This distinctive structure represents a fascinating chapter in Australian lighthouse construction—entirely prefabricated in England from cast iron plates, shipped halfway around the world, and assembled on site at the end of the newly constructed breakwater. Its hexagonal design with a graceful copper dome remains unique among Australian lighthouses, originally painted in striking red and white bands that made it unmistakable to approaching vessels.

The Breakwater Lighthouse stands 12 meters tall, its light positioned 14 meters above sea level. For decades, it served as the primary navigational guide for vessels entering the busy coal port, its light a welcome sight for mariners from near and far.

By the 1930s, however, increased shipping and larger vessels and the transition of commercial shipping to Port Kembla necessitated a more powerful beacon positioned at greater height. In 1936, the Wollongong Head Lighthouse was constructed on Flagstaff Hill, 33 meters above sea level. Built of reinforced concrete in a modernist style typical of interwar lighthouse design, the white tower stands 16 meters tall and projects a powerful beam visible for 19 nautical miles. The light characteristic—one white flash every 10 seconds—has become a familiar rhythm to generations of sailors navigating these waters.

to the harbour and CBD beyond

Life for the keepers of these lighthouses embodied both privilege and hardship. While not as isolated as their counterparts on remote islands like Montague, they nonetheless maintained a constant vigil through wild storms and calm seas alike. The Breakwater Lighthouse required keepers to haul fuel and supplies along the exposed breakwater path—a treacherous journey during heavy seas when waves would crash over the stone barrier. The Head Lighthouse, while more accessible, demanded equal vigilance and responsibility.

With the advent of automation, on station keepers became unnecessary. The Head Lighthouse was automated in 1974, its operations now controlled remotely by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. Meanwhile, the older Breakwater Lighthouse had been decommissioned as the main navigational aid in 1936 but continued to operate as a minor light specifically guiding vessels into the harbour entrance.

Like many Australian lighthouses, Wollongong’s beacons have their share of legends and tragedies. Local folklore tells of a keeper’s wife who, during a violent storm in the late 19th century, maintained the Breakwater light through the night after her husband was injured by falling equipment. Another tale recounts how a catastrophic wave in 1888 completely submerged the Breakwater Lighthouse, smashing its windows and flooding the interior—yet remarkably, the dedicated keeper managed to keep the light burning throughout the tempest.

The Illawarra coastline has a tragic maritime history, with numerous shipwrecks highlighting the treacherous nature of the region’s waters. Some notable maritime disasters include:

The steam collier Kiama ran aground near Wollongong during a severe storm on 5 August 1887. Despite being close to shore, the vessel broke apart in rough seas, resulting in the loss of several crew members. The incident underscored the critical importance of lighthouses in guiding vessels away from the rocky coastline.

The sailing vessel Paton was driven onto the rocks near Flagstaff Point during a violent southeast gale in 1890. The ship’s destruction was witnessed by horrified local residents, who could do little to assist as the vessel was dashed against the rocky shoreline. Only a portion of the crew survived, highlighting the unforgiving nature of the Wollongong coast.

In 1927 the SS Momus, a coastal trader, encountered extreme difficulty near Wollongong during a particularly violent storm. While not directly wrecked in the harbour, the incident resulted in multiple casualties and drew attention to the dangerous maritime conditions of the region.

During the 1930’s multiple coal ships servicing the local mining industry met tragic ends along the Wollongong coast. The narrow harbour entrance and prevailing weather conditions made navigation extremely challenging for vessels carrying coal from the region’s numerous mines.

On 16th May, 1943 during WWII the US fuel supply ship SS Cities Service Boston ran aground and was broken up on Bass Point of Shell Harbour. Of the crew of 62 all but four survived.

In February 1949 the coastal steamer SS Bombo capsized during a gale off Port Kembla, of the twelve crew only eight survived, including the ships dog Brownie who managed to swim to shore.

Long before European settlement, the Dharawal people would have experienced maritime tragedies. Traditional stories speak of dangerous sea journeys and the loss of fishing vessels, though specific documented accounts are limited.

The waters around Wollongong continue to claim lives occasionally. In 1998, a fishing vessel capsized near the harbour entrance despite the guidance of both lighthouses, resulting in the loss of three lives. Marine emergencies remain a regular occurrence in these waters, with the lighthouses playing vital roles in search and rescue operations.

To prove the point on the morning of my visit a recreational boat washed up on the beach below Flagstaff hill, there was no sign of life or indication of what had happened and no reports of missing boats or people. Local police and media were making enquiries and by the time I left it was still an unsolved mystery.

when I was visiting on the 26th March, 2025

After a period of neglect that threatened its very existence, the historic Breakwater Lighthouse underwent comprehensive restoration in the 1970s and again more extensively in 2000-2002. The painstaking work preserved its unique iron structure and distinctive copper dome for future generations, earning heritage protection under the New South Wales State Heritage Register.

The Head Lighthouse remains an active aid to navigation, while the Breakwater Lighthouse serves both as a minor navigational light and a beloved icon of Wollongong’s maritime heritage. Together, they stand as testament to Australia’s seafaring past and the ongoing relationship between a coastal city and the sometimes perilous waters that have shaped its history.