Location:

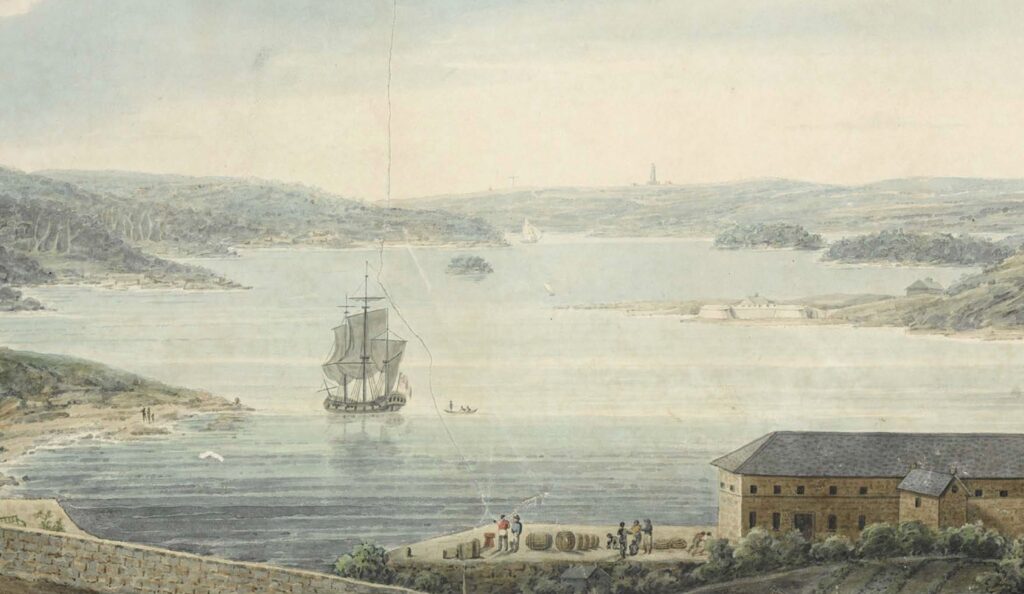

Macquarie Lighthouse is Australia’s oldest lighthouse, first lit in 1818. It’s located at the southern entrance to Sydney Harbour atop sheer sandstone cliffs and stands 105 meters above sea level. The lighthouse occupies a strategic position that allows its beam to be visible far out to sea while also guiding vessels through the critical final approach to Sydney Heads.

The geological formation of the headland consists of Hawkesbury sandstone, the same material used in the lighthouse’s construction. The site offers panoramic views spanning from North Head to Bondi Beach, making it not just a crucial navigation aid but also an important observation point for monitoring shipping movements and weather conditions.

The surrounding area has changed dramatically since the lighthouse’s construction, transitioning from isolated headland to prestigious residential suburb. Despite this urban development, careful planning regulations have ensured the lighthouse maintains its clear lines of sight and operational effectiveness.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 33° 51′ 22″ S Long: 151° 17′ 07″ E

First Lit: 1818 (original), 1883 (current), Automated 1976

Tower height: 21 meters

Focal Height: 105m above MSL

Original Lens: First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens

Range: 25 nautical miles

Characteristic: Flash every 10 seconds [Fl.W. 10s]

Indigenous History:

The Birrabirragal people of the Eora Nation knew this headland intimately long before European ships appeared on the horizon. They called it “Burrabra,” meaning “high point” or “lookout place,” and if you stand here at dawn during whale migration season, you’ll understand why. For countless generations, their lookouts watched from these cliffs, monitoring the movements of fish, tracking whale migrations, and maintaining navigation fires that guided people along the coast.

The archaeological evidence they left behind tells stories of a rich and complex relationship with this landscape. Shell middens hidden in the cliff faces speak of feasts and gatherings, while rock engravings preserve their Dreamtime stories in stone. When you walk these clifftops today, you’re walking paths that have been used for thousands of years.

Colonial History:

The story of Macquarie Lighthouse begins with tragedy. In the early years of the colony, ships would approach Sydney Heads with trepidation, especially at night. The 1803 wreck of the HMS Porpoise served as a brutal reminder of the coast’s dangers, but it would take another decade of lost ships and lives before action was taken.

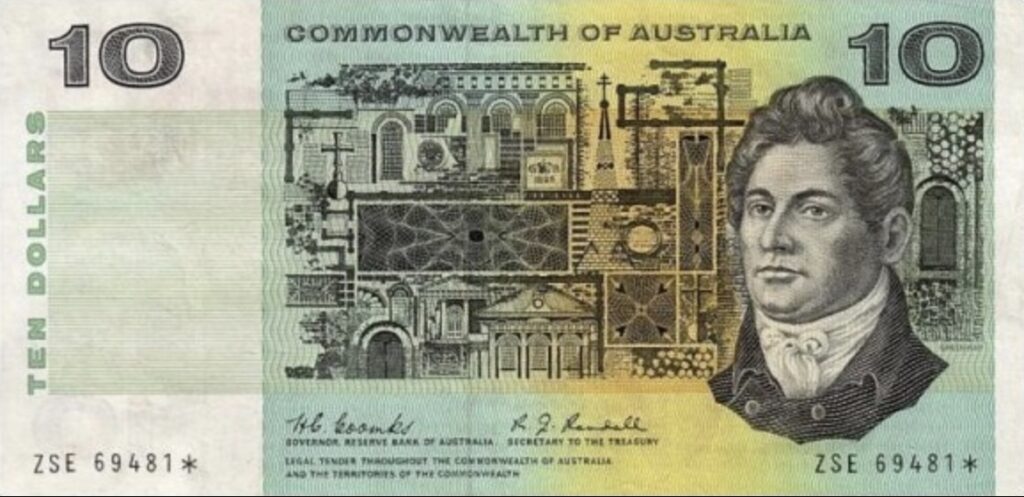

Enter Governor Lachlan Macquarie, a man with vision enough to see past a convict’s chains to the architect within. His choice of Francis Greenway to design Australia’s first lighthouse raised eyebrows among the colony’s free settlers, but Macquarie knew talent when he saw it. The governor’s faith would be repaid in sandstone and light.

Greenway took to the task with the passion of a man with something to prove. His design wasn’t just functional – it was beautiful. As the tower rose from the clifftop in 1816, even his critics had to admit that something remarkable was taking shape. Local sandstone blocks, cut and shaped by convict hands, slowly climbed skyward. Every detail was considered, from the elegant tapering of the tower to the innovative lantern room design that would maximize the light’s reach.

The day the lighthouse first shone in 1818 marked more than just a triumph of engineering – it was a symbol of the colony’s transformation from a penal settlement to a proper maritime nation. Greenway’s reward was his freedom, granted by a governor who understood that true worth isn’t determined by a person’s past.

Greenway’s original design showed remarkable sophistication for its time. The lighthouse incorporated a distinctive tapering tower with external buttressing, an innovative lantern room design that maximized light output, and integrated the keeper’s quarters into the base of the tower.

Construction began in 1816 using local sandstone and convict labor. The project faced numerous challenges including the difficulty in transporting materials to the exposed site, the limited availability of skilled stone masons, technical challenges in creating precision optical equipment locally and financial constraints due to the colony’s limited resources

The lighthouse was completed in 1818 and immediately proved its worth, significantly reducing shipping accidents at the harbour entrance. The original light source was an array of oil lamps with parabolic reflectors, representing the most advanced technology available at the time.

The quality of Greenway’s work impressed Governor Macquarie so much that he granted the architect his emancipation, marking a significant moment in colonial history where convict skills were recognized and rewarded.

The success of Macquarie Lighthouse established important precedents for colonial architecture and engineering. It demonstrated the viability of large-scale public works in the colony, it proved the quality of local sandstone as a building material, it established standards for maritime safety infrastructure and it showed the potential for convict labor in skilled construction work.

However, by the 1870s, serious structural problems became apparent in the original lighthouse. The sandstone used in construction was of variable quality, and some blocks began to deteriorate badly. Despite attempts at repairs, it became clear that a new structure would be needed.

The decision to replace rather than repair the lighthouse sparked considerable debate in the colony. Many argued for preserving Greenway’s historic structure, while others emphasized the critical need for a reliable navigation aid. The compromise solution was to build an exact replica using better materials and incorporating modern technology.

The Lighthouse:

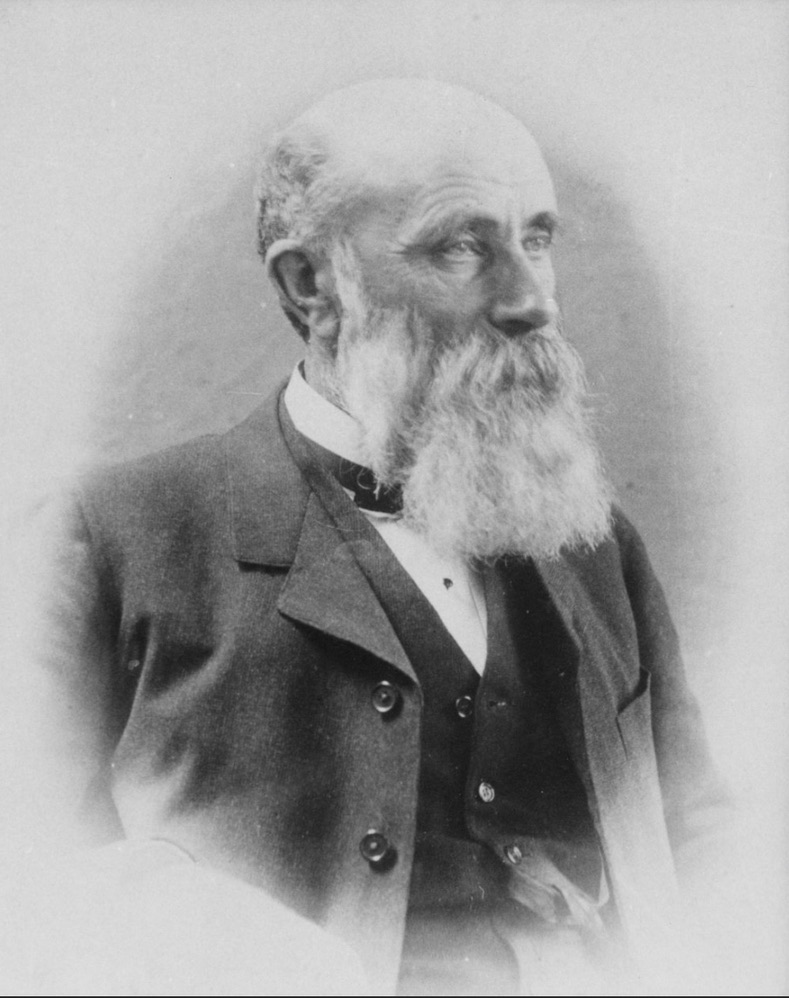

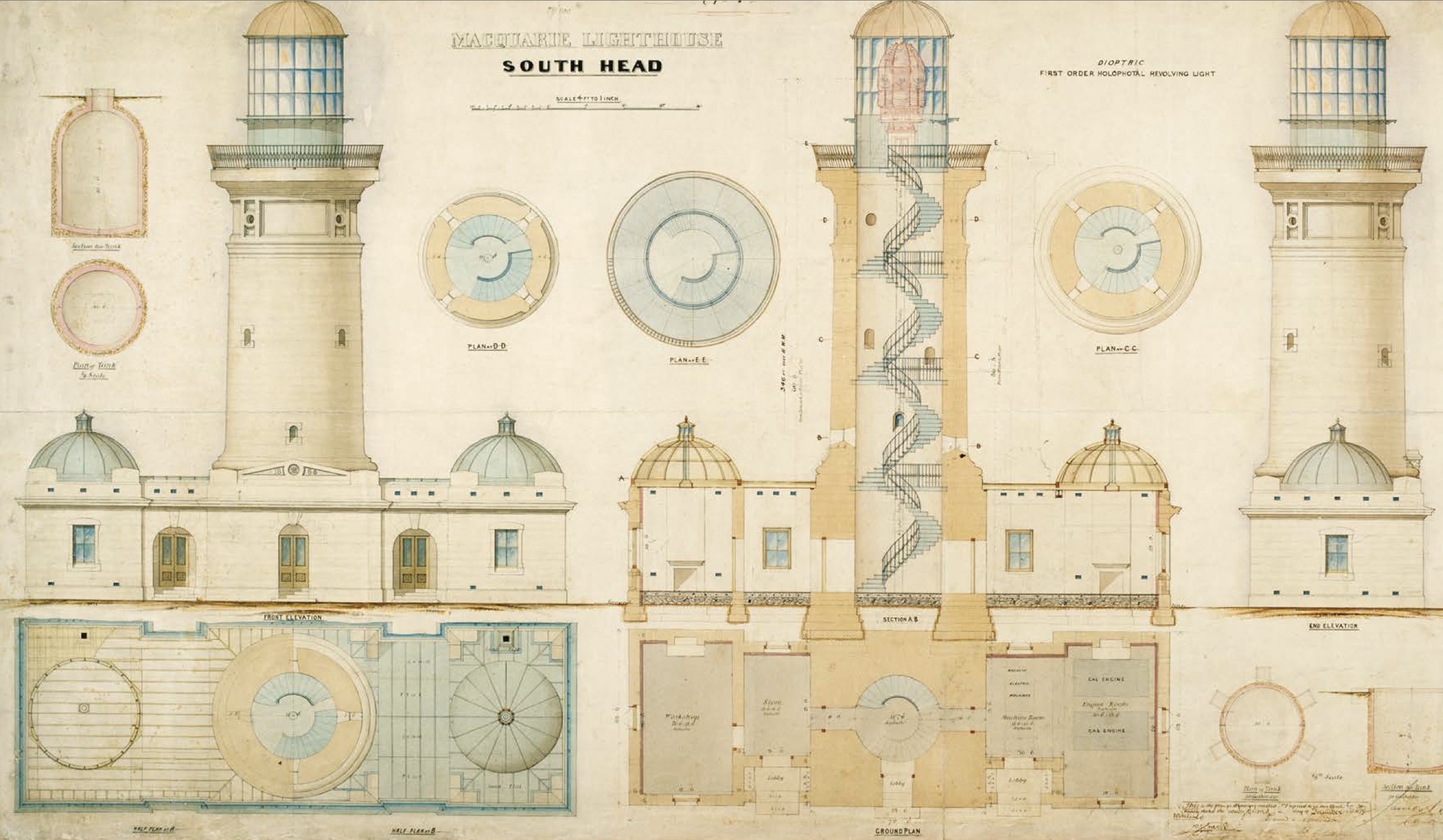

The present Macquarie Lighthouse, completed in 1883, represents a unique moment in Australian architectural history where a significant structure was deliberately replicated to preserve its historic design. Colonial Architect James Barnet was tasked with creating an exact copy of Greenway’s original while incorporating modern improvements and more durable materials.

Barnet’s design maintained Greenway’s classical proportions while making several crucial improvements, including higher quality sydneyite sandstone specially selected for durability, enhanced foundation design incorporating latest engineering principles, improved ventilation system to protect the optical apparatus, more spacious keeper’s quarters with better living conditions, improved drainage systems to prevent water damage and a reinforced lantern room designed for newer optical equipment.

The construction process, which began in 1881, was meticulously documented to ensure it replicated the original design. Stones were quarried from specially selected sites in Pyrmont and each block was cut to exact specifications using steam-powered machinery and a temporary railway was constructed to transport materials up the headland. The new tower was built just 4 meters inland from the original and the construction took 27 months, employing up to 50 workers during peak periods.

Technical Details:

The technical evolution of Macquarie Lighthouse reflects the history of lighthouse illumination technology from the early 19th century to the present day.

Original 1818 Apparatus

The first lighting system consisted of: 16 argand oil lamps with parabolic reflectors, a rotating mechanism powered by clockwork with a manual winding system requiring hourly attention, signal flags and cannon for daylight communication and specially imported optical glass from England.

The 1883 Installation

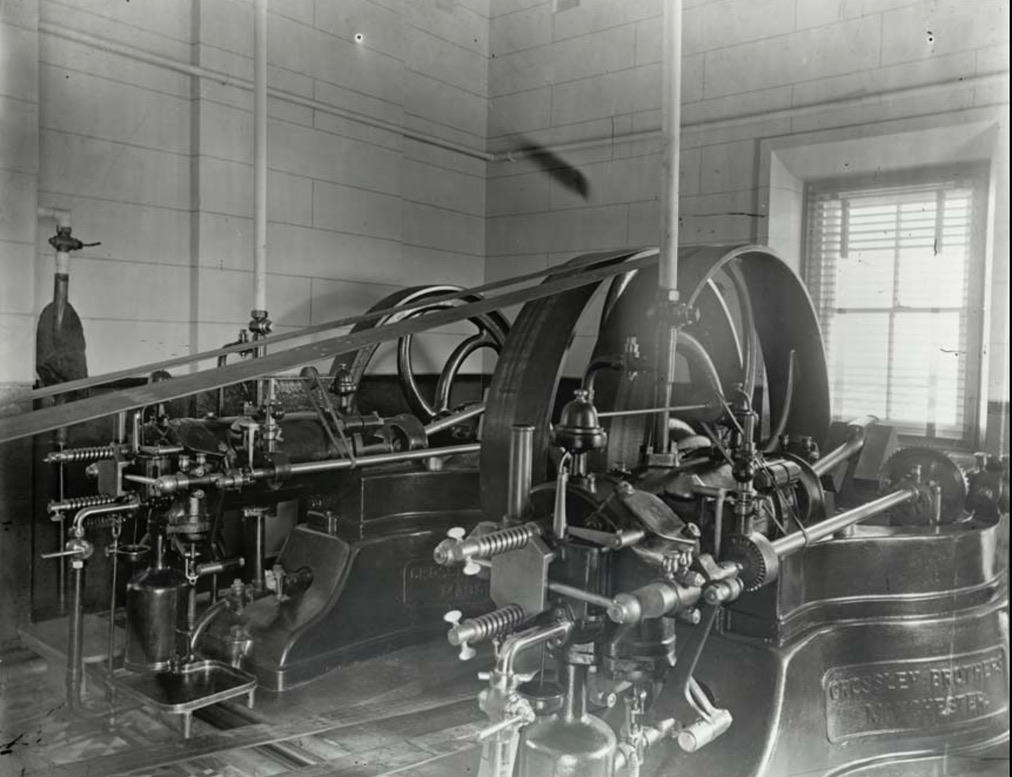

The new lighthouse featured state-of-the-art technology including a First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens seated on a hydraulic mercury float rotation system controlled by a modern clockwork mechanism, advanced ventilation for the optical apparatus, improved fuel delivery systems and electric telegraph communication equipment.

Keepers of the Light:

The position of keeper at Macquarie Lighthouse was one of the most prestigious in the colonial lighthouse service, requiring not just technical skill but also administrative ability and social grace due to the station’s proximity to Sydney. After all, this was no remote outpost; the keeper of Macquarie Light was as likely to entertain government officials as to rescue shipwrecked sailors. To be appointed keeper at Macquarie Lighthouse was to join an elite fraternity. This wasn’t just any lighthouse – this was Australia’s first, standing guard over the nation’s busiest harbor.

Robert Watson, our first keeper, set standards that would guide generations to follow. Every evening, as the sun dipped behind the Blue Mountains, he would climb the tower stairs, trim his lamps, and set in motion the clockwork mechanism that would keep them rotating through the night. His family lived below in the cottage, their lives governed by the rhythm of the light above. Tragically, Watson himself would be claimed by the very waters he worked to protect, lost in a boating accident that left his family to carry on without him.

James Wilshire brought a methodical mind to the position in 1822. His carefully maintained logbooks read like a weather almanac, recording every shift in wind and visibility. The systems he developed for keeper training and weather observation would influence lighthouse practices across the colony. Late at night, he could often be found in the lantern room, using the excellent vantage point to study the stars and weather patterns.

George Mulhall’s tenure from 1848 to 1869 saw the lighthouse through some of its most challenging times. He had an almost supernatural ability to sense approaching storms, often preparing the emergency systems hours before the official weather warnings arrived. His wife Mary became known as something of a folk healer, tending to injured sailors and locals alike with her collection of home remedies.

Herbert Bache witnessed perhaps the most dramatic period in the lighthouse’s history – the transition from old tower to new. For months in 1883, he managed both structures, coordinating the delicate transfer of the optical apparatus while ensuring the light never failed. His diaries provide fascinating insights into this unique moment, when two identical towers stood side by side on the headland.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

Despite the lighthouse’s presence, the approaches to Sydney Harbour have witnessed numerous maritime disasters. The treacherous combination of strong currents, hidden reefs, and severe weather conditions has challenged even the most experienced mariners.

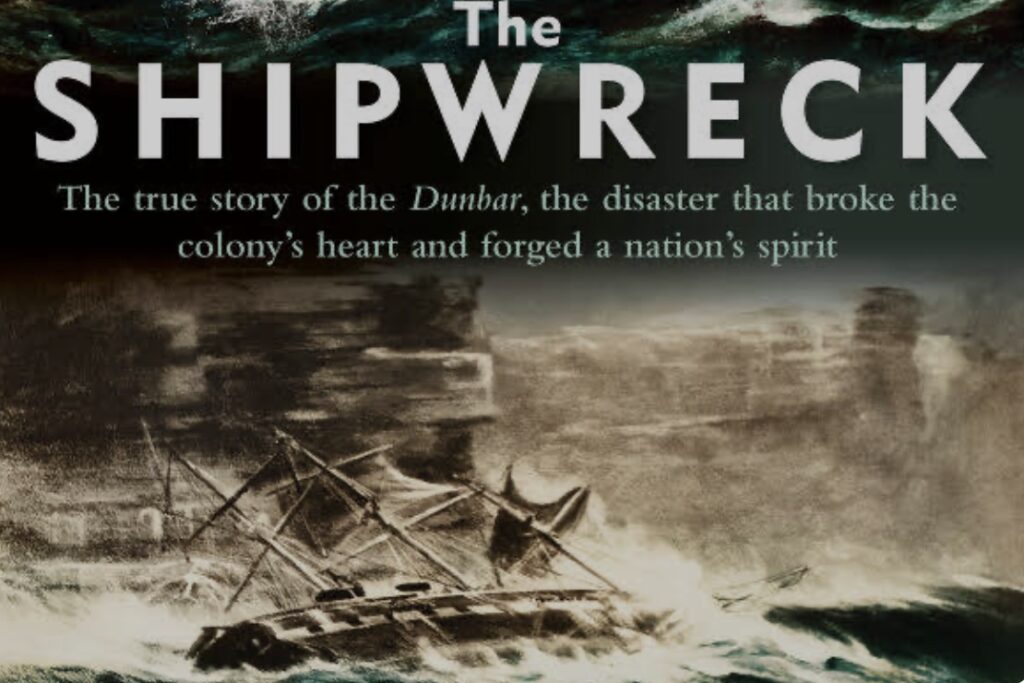

No story of Macquarie Lighthouse would be complete without remembering the Dunbar tragedy of 1857. The night of August 20th began with a howling storm – the kind that made keeper George Mulhall double-check every lamp and fitting. Out in the darkness, the passenger ship Dunbar was approaching after its 81-day journey from England.

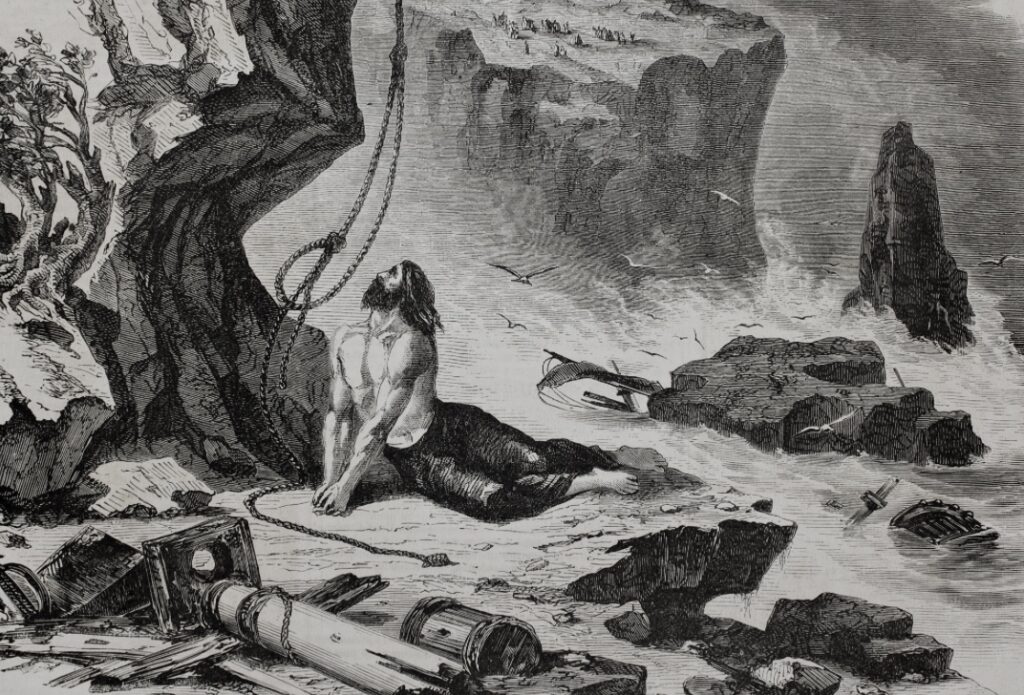

What happened next would haunt Sydney for generations. Perhaps deceived by rain and darkness, the captain mistook the entrance to Sydney Harbour. The Dunbar struck the cliffs directly below the lighthouse, where the waves showed no mercy. Of 122 souls aboard, only one survived – James Johnson, thrown by chance onto a rock ledge where he clung through the night as the lighthouse beam swept overhead, illuminating fragments of the unfolding tragedy.

Barely had the city recovered when the Catherine Adamson went down near North Head, claiming another 21 lives. These twin tragedies of 1857 shocked the colony into a comprehensive review of maritime safety and resulted in the urgent commissioning of the Hornby Light to complement Macquarie and mark the southern entrance to the harbour.

Notwithstanding these improvements and modern navigations aids the treacherous waters at the entrance to Port Jackson continue to claim ships and steal sailors lives, from the earliest recorded loss in 1803 and everyuntil as recently as December, 2024.

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many historic lighthouses, Macquarie Lighthouse has accumulated its share of mysteries and unexplained phenomena over two centuries of operation.

Some of the more unique paranormal activities observed here date back before European settlement and are told in Indigenous oral histories speaking of ancient fires and the spiritual and cultural significance of this highest point on the coast.

There are also numerous reports of people seeing “Greenway’s Ghost” which was first reported during the construction of the second tower and reappears during major maintenance. It’s almost as if he’s still overseeing work on his most prized project.

Similarly, there are reports of “Watsons Ghost” as there are conflicting accounts as to how he met his untimely death, was it an accident or was foul ply involved?

There are also a range of the more usual occurrences such as unexplained footsteps and voices, mysterious lights and a range of technical aberrations such as clock irregularities, power fluctuations and signal interference.

Current Status:

Today’s Macquarie Lighthouse stands as a perfect blend of past and present. Automated since 1976, its operation is now managed by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority with a precision its first keepers could only have dreamed of. Yet step inside the tower, and you’ll find yourself walking through layers of history. The massive Fresnel lens still rotates in its bath of mercury, just as it has since 1883. The keeper’s quarters still echo with the footsteps of generations who lived their lives by the light above.

Each year, thousands of visitors climb the same stairs that Robert Watson first ascended in 1818. They stand in the lantern room where countless keepers maintained their vigilant watch and look out over waters that hold two centuries of stories. The view remains unchanged – the endless horizon, the meeting of sea and sky, the distant ships making their way home.

The lighthouse’s beam still sweeps out across the waters every ten seconds, continuing a tradition of guardianship that stretches back to the first Indigenous fire beacons. In a world of GPS and satellite navigation, there’s something profoundly reassuring about this steady pulse of light cutting through the darkness, a reminder that some things remain constant even as the world changes around them.

Macquarie Lighthouse is more than just Australia’s oldest lighthouse – it’s a living reminder of our maritime heritage, a testament to human ingenuity and dedication, and a continuing guardian of our waters. Its story, like its light, shines on.