Location

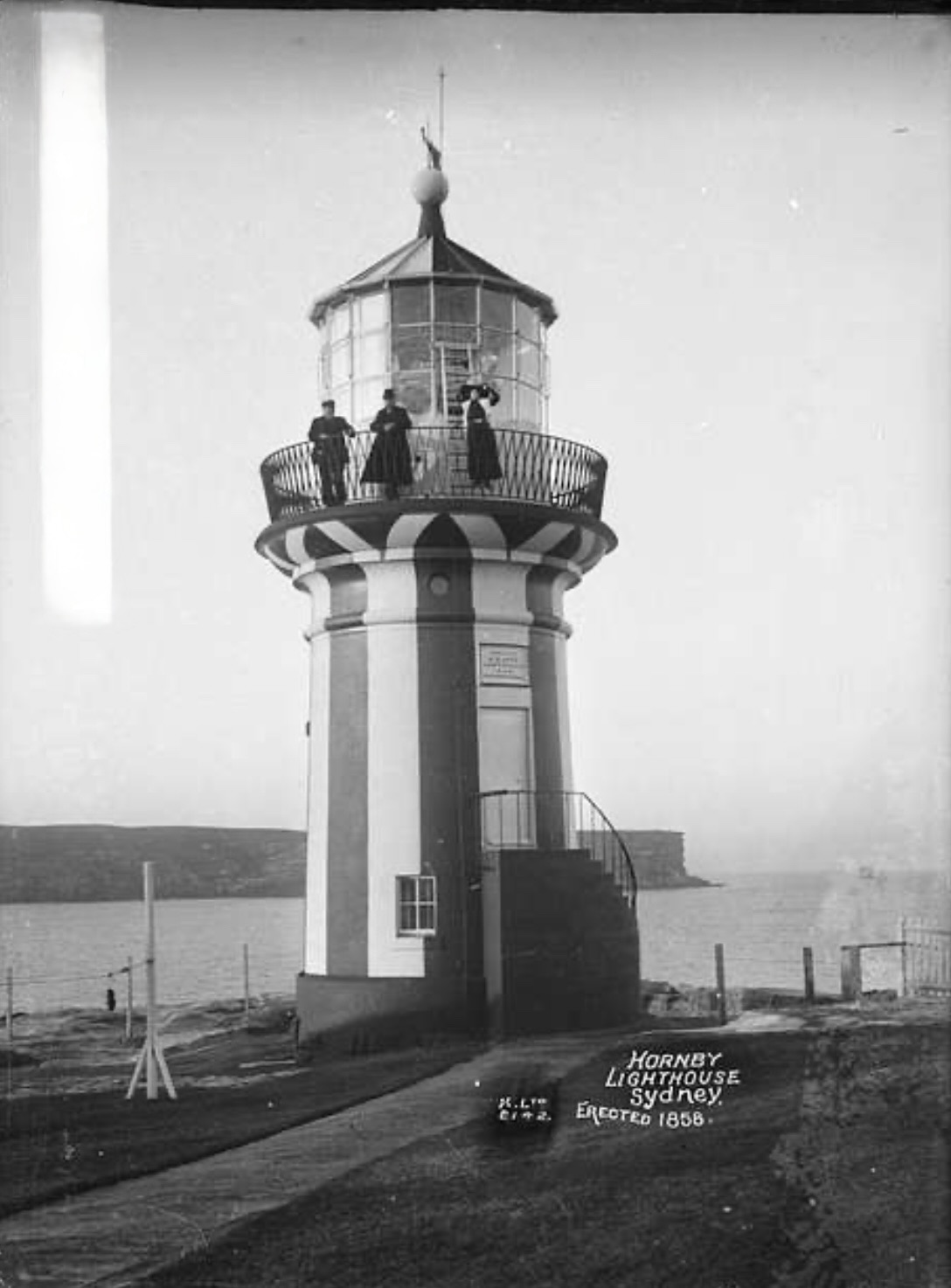

Hornby Lighthouse stands at the tip of South Head, guarding the southern entrance to Sydney Harbour. Perched 27 meters above sea level, it overlooks the confluence of the Pacific Ocean and the sheltered waters of the harbour.

Summary

- GPS: Lat: 33° 50′ 01″ S, Long: 151° 16′ 52″ E

- First Lit: November 2, 1858

- Tower Height: 9 meters

- Focal Height: 27 meters above MSL

- Original Lens: Fixed catoptric lens

- Intensity: ~ 700,000 candela

- Range: 26 nautical miles

- Characteristic: White flash every 10 seconds [Fl.W. 10s]

Indigenous History

The South Head area, including the site of Hornby Lighthouse, falls within the traditional lands of the Birrabirragal people of the Eora Nation. Known as “Car-rang-gel” in their language, this headland was a significant cultural and practical site for millennia. It served as a lookout for spotting fish, whales, and approaching visitors, while its elevated position offered a vantage point for ceremonial activities tied to the sea.

Colonial History

European interest in South Head began with Captain James Cook’s sighting in 1770, followed by Governor Arthur Phillip’s exploration of Sydney Harbour in 1788. The headland’s strategic value was evident as a control point for the harbour’s entrance, leading to early signal stations and fortifications.

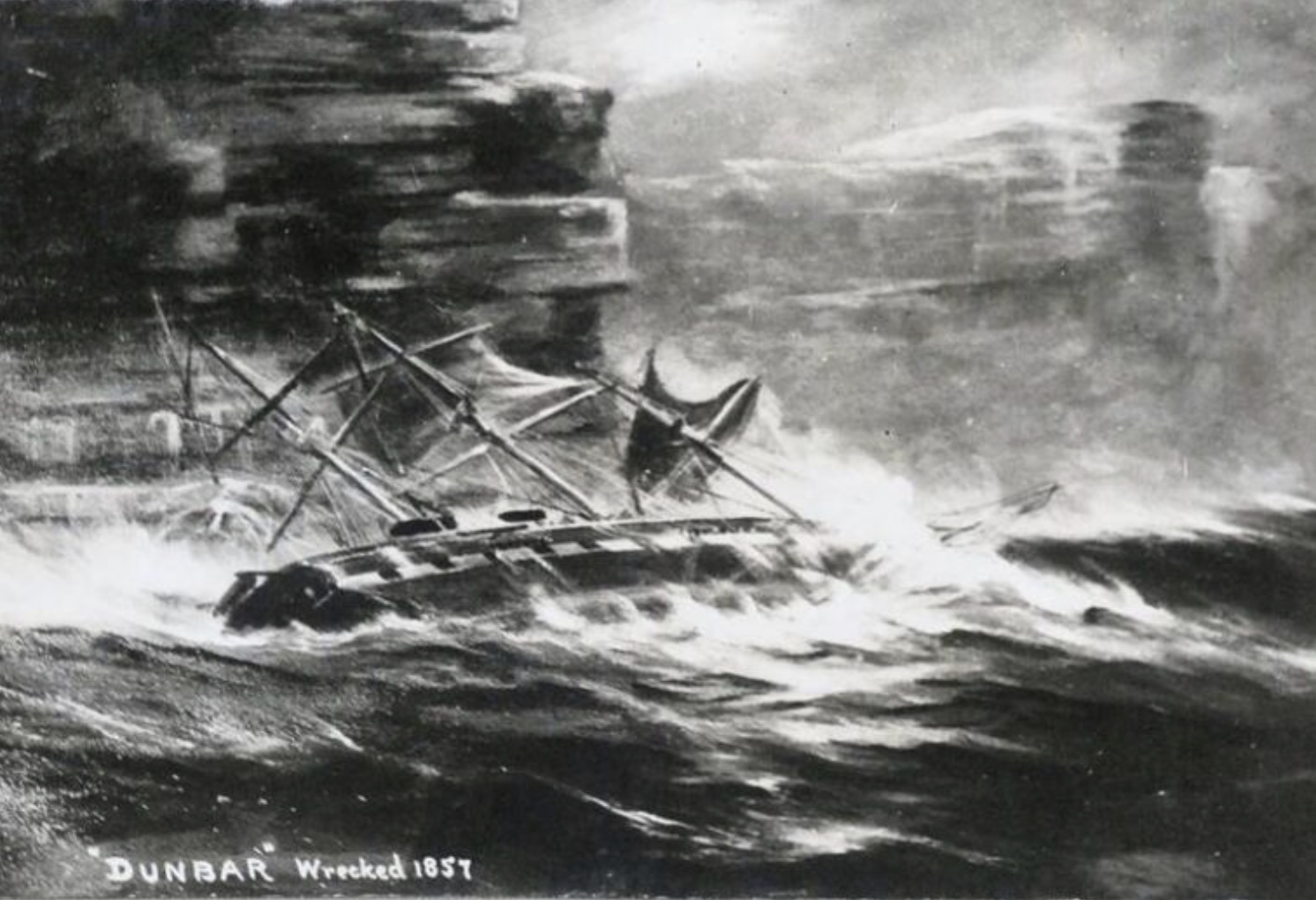

The catalyst for Hornby Lighthouse came with the catastrophic wreck of the Dunbar in 1857, which sank off South Head, claiming 121 lives. This disaster, followed by the loss of the Catherine Adamson later that year, underscored the need for a permanent navigation aid. Designed by colonial architect Mortimer Lewis and supervised by Alexander Dawson, the lighthouse was completed in 1858. Its name honours Admiral Sir Phipps Hornby, a prominent British naval figure, reflecting its maritime significance.

The Lighthouse

Commissioned in response to the Dunbar tragedy, Hornby Lighthouse was designed by Mortimer Lewis in a simple yet striking style. Construction began in 1857 using locally quarried sandstone, transported up the steep cliffs by convict labour and basic pulley systems.

The lighthouse was first lit on November 2, 1858, a mere 15 months after it was fist commissioned in the aftermath of the Dunbar and Catherine Adamson tragedies. O

Its iconic red and white vertical stripes—added later for visibility—distinguish it from other coastal structures, blending practicality with aesthetic charm. The lighthouse’s compact design reflects its role as a harbor marker rather than a long-range coastal light, complementing the nearby Macquarie Lighthouse 3km to the south.

The Buildings

The lighthouse tower, standing 9 meters tall, is built from sandstone blocks with walls nearly a meter thick at the base, tapering upward to support a small lantern room. Its design is utilitarian, with a simple gallery and railing, reflecting Lewis’s pragmatic approach. Adjacent to the tower are two keeper’s cottages, constructed in a modest Victorian style from the same golden sandstone, providing basic accommodation while maintaining clear sightlines to the light. A small oil store, boathouse and jetty completed the complex..

Keepers of the Light

Hornby’s keepers were a dedicated group, living in relative isolation to ensure the safety of Sydney’s maritime traffic.

The first keeper, James Johnson (1858–1870), was ironically the sole survivor from the Dunbar wreck and saw it as his duty to help prevent future maritime disasters. At the end of his 12 year tenure he transferred to be head keeper at Nobbys’ lighthouse at Newcastle and was replaced as head keeper by his son John who continued the family tradition and maintained the routines and detailed record keeping instituted by his father. Edward Watson (1875–1889) is best remembered for his detailed stability weather and sea condition observations which aided local shipping. His tenure saw the addition of the distinctive stripes, a practical enhancement he championed. Later, Thomas Marshall (1900–1915) primary legacy was overseeing the transition to electrification. The final keeper, William Harris (1930–1945), served through World War II, maintaining blackout protocols and coastal watches.

Automation arrived in the 1940s, ending nearly a century of manned operation. Their legacy endures in the preserved cottages and historical records.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies

The waters off South Head have a grim history of maritime disasters, with the Dunbar wreck of 1857 being the most infamous. On the night of August 20, 1857, the clipper ship Dunbar, approaching Sydney after an 81-day journey from England, encountered a fierce storm. Mistaking the entrance to Sydney Harbour in the darkness, the ship struck the cliffs below South Head. Of the 122 people aboard, only one survived – James Johnson, who clung to a cliff face for 36 hours before he was rescued, and who was to become the first keeper at the lighthouse that built to prevent similar

The Dunbar disaster sent shockwaves through colonial Sydney. Many of the passengers were prominent citizens returning home, and the loss of life represented the colony’s worst maritime disaster. The tragedy’s impact was compounded just months later when the Catherine Adamson was wrecked on North Head in similar circumstances, claiming another 21 lives.

These disasters directly led to the construction of Hornby Lighthouse, but even after its construction, incidents persisted. In 1868, the schooner Ellen foundered nearby, though the lighthouse aided rescue efforts. The Queen of Nations was wrecked in 1881 during a severe storm and the Woniora was lost in 1882 with all hands. In1902 the SS Kelloe collided with the Dunmore and sank though quick action by the lighthouse keepers helped prevent loss of life. The MV Malabar’s wreck in 1931 proved another significant incident, with the ship giving its name to the nearby beach where it came to grief.

During World War II, the 1942 Japanese submarine attack on Sydney Harbour saw Hornby’s keepers on high alert, guiding defensive vessels. More recently, the 1985 grounding of the yacht Southern Cross highlighted the ongoing need for vigilance, with the lighthouse coordinating rescue operations.

Myths & Mysteries

Hornby Light has accumulated its share of unexplained phenomena and enduring legends over the past 167 years, many connected to the tragic history of the harbor entrance.

The Birrabirragal people speak of the headland as a place of spiritual significance, with traditional stories of supernatural phenomena predating European settlement. These accounts often reference unusual light phenomena visible from the cliffs, particularly during significant astronomical events. Visitors also report strange mists and lights near the cliffs, especially during whale migrations, echoing Birrabirragal traditions.

Over the years there have been numerous reports of a ghostly figure, believed to be an unidentified keeper lost to the cliffs, seen pacing the tower during storms. Keeper Edward Watson’s logs also note unexplained lantern flickers, blamed on restless spirits from the Dunbar.

The lighthouse complex has generated numerous unexplained occurrences, many centred around the anniversary of the Dunbar tragedy. Multiple keepers documented mysterious phenomena, particularly during storms that mirror historical shipwrecks.

The keeper’s cottages have their own collection of unexplained events, with former residents reporting unusual experiences, particularly in the vicinity of the original head keeper’s quarters. These reports often coincide with significant dates in the lighthouse’s history.

In the 1970s, renovation workers found a hidden cache of 19th-century tools beneath the cottages, their origins a mystery. These tales enhance Hornby’s allure, blending history with the supernatural

Current Status

Hornby Lighthouse remains an active navigation aid, managed by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and maintained by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service within Sydney Harbour National Park. Fully automated since the 1940s, it blends historic design with modern technology. Listed on the State Heritage Register, the site is open to the public via a scenic walk from Watsons Bay, drawing visitors for its history and views.

Hornby stands as both a functional beacon and a cherished piece of Sydney’s maritime heritage.

A Personal Note

Hornby Lighthouse holds a special place as a symbol of resilience and beauty. Its modest stature belies its profound impact, guiding countless vessels through Sydney’s gateway. Visiting its windswept perch, one can’t help but feel connected to the keepers, mariners, and Indigenous custodians who shaped its story—a timeless memorial to those lost at sea.