Location:

Nobby’s Lighthouse stands on top of Nobby’s Head at the entrance to Newcastle Harbour, New South Wales. The lighthouse rises 35 m above sea level and is strategically positioned to guide vessels into what has become one of Australia’s busiest ports. Its location at the mouth of the Hunter River makes it a crucial navigational aid for both commercial shipping and recreational vessels.

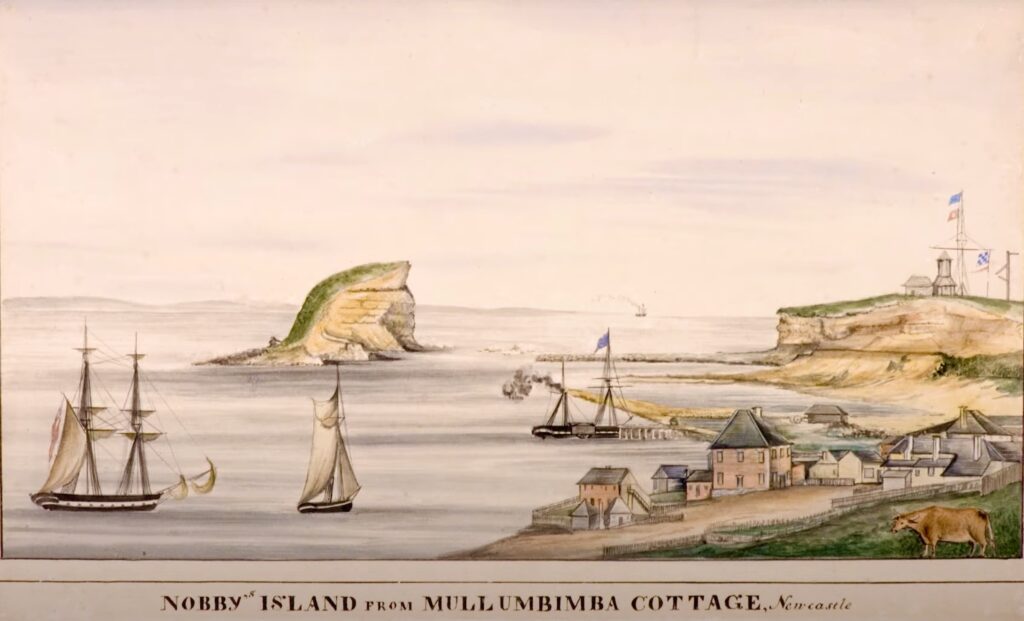

Originally Nobby’s Head was a small island rising approximately 62 m above sea level connected to the mainland by a reef that was occasionally exposed at low tide. The island’s striking profile made it a natural beacon for early maritime traffic, even before the construction of the lighthouse. Today, it forms the end point of a breakwater that helps protect Newcastle Harbour and is now permanently joined to the mainland at Signal Head by a rock stabilised sand spit.

The site experiences dramatic weather conditions, particularly during east coast low pressure systems when wind speeds can exceed 100 km/h. The exposed position means the lighthouse bears the full force of storms rolling in from the Tasman Sea, while also having to withstand salt spray and extreme temperature variations throughout the year.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 32° 55′ S Long: 151° 47′ E

First Lit: January 1, 1858 (Automated 1934, Demanned 1984)

Tower height: 9.1 m

Focal Height: 35 m above MSL

Original Lens: First Order Chance Brothers Dioptric

Intensity: 580,000 candela

Range: 24 nautical miles

Characteristic: Three white flashes every 20 seconds [Fl. (3)W 20s]

Indigenous History:

The area around Nobby’s Head holds deep significance for the Awabakal people, who are the Traditional Owners of the land. In Awabakal tradition, the headland is known as Whibayganba, and features prominently in their Dreamtime stories. According to these stories, Whibayganba was once a great sea creature that had been speared by a legendary warrior, turning into the distinctive island formation.

Archaeological evidence indicates continuous Aboriginal occupation of the surrounding area for tens of thousands of years. The headland served as an important lookout point and fishing location, with the surrounding waters and shoreline providing abundant food resources. Shell middens and tool-making sites discovered in the vicinity testify to the long history of Indigenous occupation and resource use.

The Awabakal people developed sophisticated fishing techniques specific to this location, taking advantage of the unique currents and tidal patterns around the headland. Their deep understanding of local weather patterns and seasonal changes informed their sustainable use of marine resources, knowledge that continues to be valued and maintained by Awabakal descendants today.

Colonial History:

The European history of Nobby’s Head began with Lieutenant John Shortland’s discovery of the Hunter River in 1797. Shortland’s charts and reports noted the distinctive island at the river’s mouth, which would become crucial to the development of Newcastle as a major port. The first colonial settlement at Newcastle was established in 1801, primarily as a place of secondary punishment for convicts.

The earliest navigational beacon dates back to 1804 when a simple coal fire was suspended in an iron basket on Signal Head at the southern side of the entrance to the Hunter River. In 1821 this was superseded by a rudimentary stone lighthouse which comprised of an oil burning light in a metal cauldron, also located on Signal Head.

Nobby’s was originally called Coal Island, and as the name suggests was the first evidence of coal in what was to become the largest coal export terminal in the World, and it was an island. A significant engineering project was undertaken between 1818 and 1846 to construct a breakwater connecting Nobby’s Island to the mainland. This massive project, largely built using convict labor, forever changed the geography of the harbour entrance and created the foundation for future port developments. The construction of the breakwater was a monumental task requiring the quarrying and placement of hundreds of thousands of tons of rock most of which came from the island and reducing it in height from 62m to the current 27.5 m.

The strategic importance of Nobby’s Head became apparent as coal mining operations expanded in the region. By the 1820s, Newcastle was developing as a significant coal port, with vessels regularly navigating the sometimes treacherous entrance to the harbour. The increasing maritime traffic highlighted the need for improved navigation aids, particularly during night time and poor weather conditions.

The Lighthouse:

The decision to construct a lighthouse on Nobby’s Head was made in response to the growing number of shipwrecks and near-misses at the harbour entrance. The colonial government approved the project in 1855, recognizing the crucial role it would play in supporting Newcastle’s expanding maritime trade.

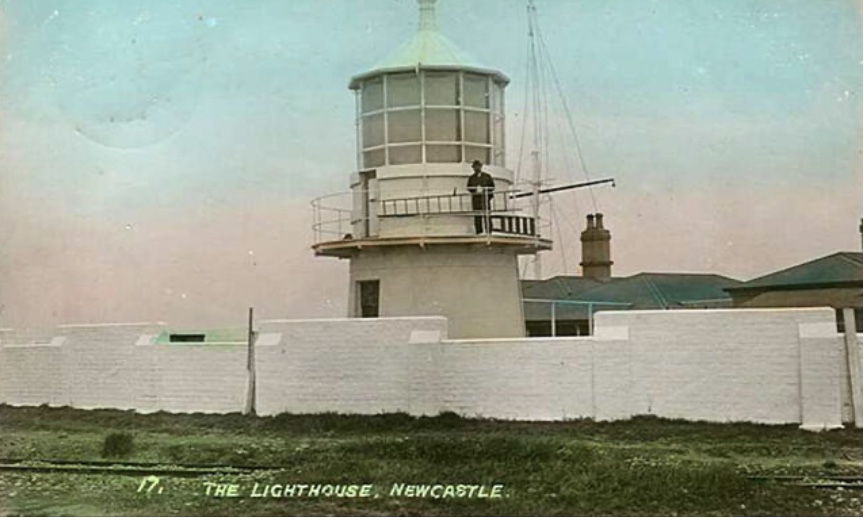

The lighthouse was designed by Alexander Dawson, the Colonial Architect, who created a elegant and functional structure that would become an iconic landmark. Construction began in 1857, utilizing local sandstone and the latest innovations in lighthouse engineering. The project presented unique challenges due to the exposed location and the need to coordinate with ongoing breakwater maintenance.

When first lit on January 1, 1858, the lighthouse featured a state of the art First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, representing the pinnacle of lighthouse technology at the time. The lighting apparatus was carefully designed to provide a distinctive signal that would be visible for up to 24 nautical miles under clear conditions.

The Buildings:

Whilst the tower is only 9.8 m tall it’s location atop the headland gives it a focal height of 35 m and a range of 24 nml. The lighthouse features distinctive Victorian architectural elements crowned by a lantern room that houses the original Chance Brothers lens.

The lighthouse complex originally included three keeper’s cottages, various outbuildings, and a signal station. The keeper’s quarters were constructed in a Victorian style, built to withstand the harsh coastal environment while providing comfortable accommodation for the lighthouse families.

The signal station played a crucial role in port operations, using flags and semaphore to communicate with vessels and coordinate shipping movements. This facility represented an early example of integrated maritime communications, combining traditional lighthouse functions with harbor control operations.

Technical Details:

The original lighting apparatus consisted of a First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, rotating on a cast iron pedestal. The initial light source was a multiple-wick oil burner, providing a characteristic white flash every 10 seconds. This system remained in operation until 1935, when it was converted to electric power.

The electrification project significantly increased the light’s intensity and reliability. The original optical apparatus was retained but modified to accommodate electric lamps, preserving the historic Chance Brothers lens while improving its effectiveness. Further modernization occurred in the 1970s with the installation of automated systems.

The original Installation (1858) used a series of oil-burning wick lamps and a fixed catoptric (reflector) array consisting of polished metal reflectors. The light source was provided by multiple wicks in sperm whale oil, later converted to colza (rapeseed) oil. The apparatus was manually rotated system requiring constant keeper attention.

The light source was upgraded to a pressurized kerosene vapor burner in 1872 and remained in operation until 1934. This system incorporated early pressure regulation system for fuel delivery but required a complex daily cleaning and maintenance routine. While it increased the luminous intensity from original oil wick system it was labour intensive required specialized kerosene storage facility on site.

Electrification Period (1934):Conversion to an electric lamp system occurred in 1934 and included the installation of early automatic lamp changer mechanism, a backup systems to cover any power failures and modifications to the original optical assembly. This advance dramatically improved the range and resulted in a reduction in manual maintenance requirements.

Since 1934 there have been constant improvements made to both the light source and automation systems the most recent of which was the conversion of the light source to a LED array replacing the traditional incandescent bulbs. This has significantly reduced power consumption and enhanced reliability and reduced maintenance needs. Computerised monitoring and control systems with automatic backup and fault detection systems are updated at regular intervals have been installed and regularly checked and updated.

Keepers of the Light:

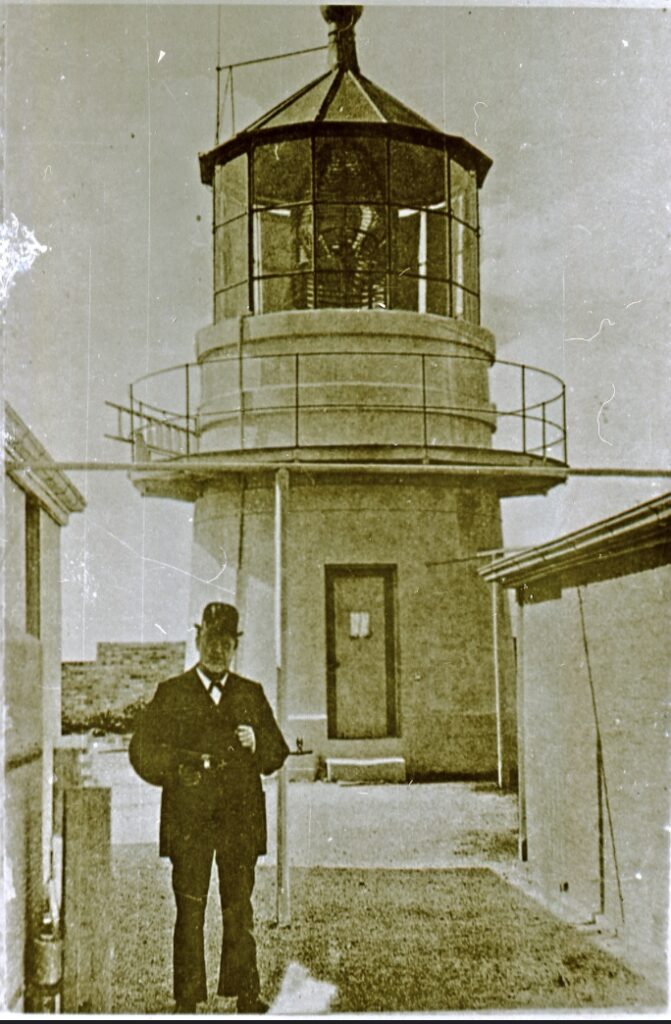

For over a century, dedicated lighthouse keepers maintained the vital service at Nobby’s. The first Principal Keeper, William Thomas, established the routines and procedures that would govern lighthouse operations for generations. Known for his meticulous attention to detail, Thomas developed a comprehensive system of watch schedules and maintenance protocols that would be followed by successive keepers for decades.

The daily routine was demanding and precise. Keepers worked in shifts, with one always on duty to maintain the light and monitor shipping movements. The day began before dawn with the extinguishing of the light and cleaning of the lens – a delicate operation that required both skill and patience. Throughout the day, keepers performed maintenance tasks, kept detailed logs, monitored weather conditions, and maintained communication with port authorities.

James Fountain’s tenure (1873-1895) saw significant technological improvements, including upgrades to the original lighting apparatus. Fountain was known for his innovations in lens maintenance and his detailed weather observations, which proved invaluable for understanding local meteorological patterns. His wife Sarah established a small school for the keepers’ children, creating an important sense of community among the isolated families.

William Manson (1895-1914) guided the station through a period of increasing maritime traffic as Newcastle’s coal trade expanded. His logbooks provide vivid accounts of numerous rescue operations and his development of improved signaling methods for communicating with ships in distress. Manson’s daughter Mary became well-known for her detailed sketches of lighthouse life, which now provide valuable historical documentation of this era.

Thomas Armstrong (1914-1929) oversaw operations during World War I, when the lighthouse played a crucial role in maintaining safe navigation while adhering to wartime security protocols. His innovative blackout procedures were later adopted by other coastal lighthouses. Armstrong’s wife Ellen served as an unofficial nurse for the lighthouse community, treating everything from minor injuries to serious illnesses.

The war years brought additional responsibilities under Head Keeper Robert Wilson (1939-1952). The lighthouse became a strategic observation post, with keepers maintaining 24-hour watches for enemy vessels and suspicious activity. Wilson developed a sophisticated code system for communicating with naval authorities and organised regular air raid drills for the keeper families.

John Harrison (1952-1968) guided the station through its transition to electric power, requiring keepers to develop new technical skills while maintaining traditional lighthouse practices. His detailed technical drawings and notes helped smooth the changeover at other stations along the coast.

The final years of manned operation under Michael Reynolds (1968-1984) saw the gradual introduction of automated systems. Reynolds ensured that traditional knowledge was documented before automation, preserving important aspects of lighthouse heritage for future generations.

Notable Head Keepers:

- William Thomas (1858-1873) – First Head Keeper

- James Fountain (1873-1895) – Known for technical innovations

- William Manson (1895-1914) – Expanded rescue operations

- Thomas Armstrong (1914-1929) – WWI security protocols

- George Patterson (1929-1939) – Depression era efficiency

- Robert Wilson (1939-1952) – WWII strategic operations

- John Harrison (1952-1968) – Electrification transition

- Michael Reynolds (1968-1984) – Final Head Keeper

The last keeper departed in 1984 when the lighthouse was fully automated, marking the end of an era of manned operation that had lasted 126 years. Each keeper and their family contributed to the rich tapestry of Nobby’s history, their stories preserved in logbooks, letters, and local memories.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

Despite the lighthouse’s presence, the waters around Nobby’s Head have witnessed numerous maritime disasters, each contributing to the evolution of maritime safety practices in Newcastle Harbour.

The SS Cawarra Disaster (1866): The loss of the SS Cawarra stands as one of Newcastle’s most devastating maritime tragedies. During a violent storm on July 12, 1866, the vessel attempted to enter the harbour despite warnings from the lighthouse. Keeper William Thomas recorded watching helplessly as enormous waves battered the ship before it capsized, resulting in the loss of 60 lives. Only one survivor, Frederick Hedges, made it to shore, rescued by local coal miners who formed a human chain into the surf. The tragedy led to significant improvements in storm warning systems and entrance procedures for the harbour.

Adolphe Shipwreck (1904): The wreck of the French four-masted barque Adolphe became one of Newcastle’s most visible maritime disasters. On September 30, 1904, while attempting to enter the harbour under tow, the ship was caught by massive waves and driven onto the Oyster Bank. Through heroic efforts by the port’s lifeboat crew, all 32 crew members were saved. The wreck remained visible for many years, serving as a sobering reminder of the harbour’s dangers and leading to improved towing procedures for sailing vessels.

SS Maianbar (1912): The SS Maianbar’s wreck illustrated the power of Newcastle’s notorious east coast storms. Despite the lighthouse’s warning signals, the vessel was driven onto Nobby’s Beach during a fierce storm. The keeper’s log describes desperate attempts to assist the crew as mountainous seas threatened to break up the ship. Though all crew members were eventually rescued, the incident led to new protocols for ships seeking shelter during severe weather.

Wartime Incident – SS Canara (1940): The SS Canara’s collision with the breakwater during wartime blackout conditions highlighted the challenges of maintaining navigation safety while adhering to wartime security measures. The incident resulted in revised blackout procedures that better balanced safety with security needs.

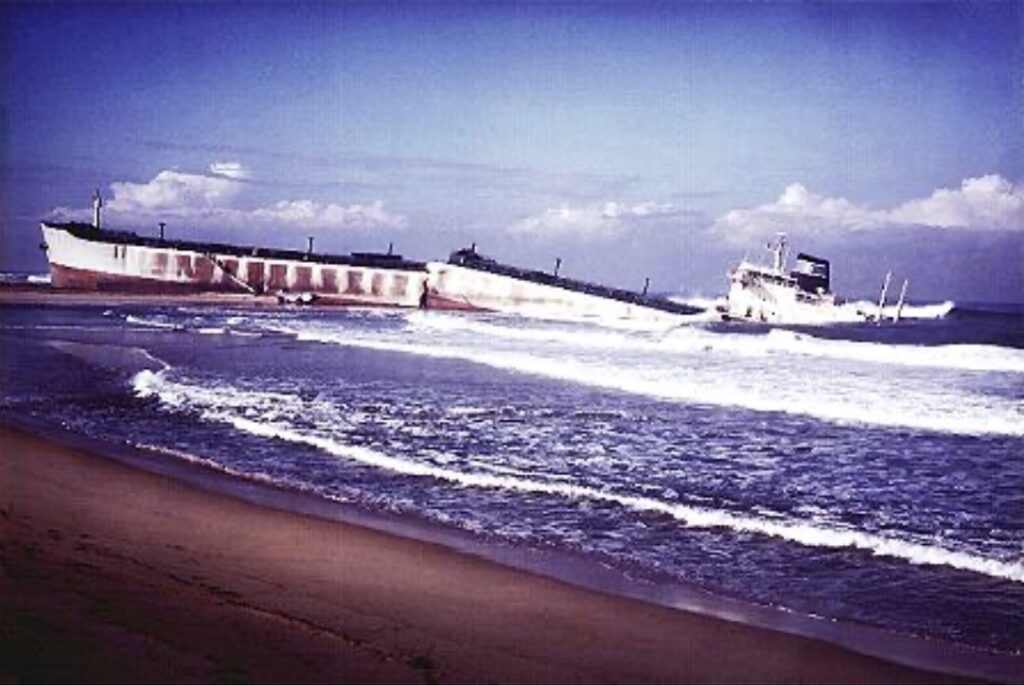

The Sygna Storm (1974): The Norwegian bulk carrier Sygna became a victim of one of Newcastle’s worst storms on May 26, 1974. Despite warnings from the lighthouse and port authorities, the ship’s anchor couldn’t hold against hurricane-force winds and 17-meter waves. The vessel was driven aground on Stockton Beach, where its remnants remained visible for many years, serving as a testament to nature’s power.

Pasha Bulker (2007): The grounding of the Pasha Bulker on June 8, 2007, demonstrated that even modern vessels with advanced navigation technology remain vulnerable to extreme weather conditions. The 40,000-tonne coal carrier ignored warnings to move further offshore as an east coast low pressure system approached. During the peak of the storm, with winds reaching 124 km/h and waves up to 17.4 meters, the ship ran aground on Nobby’s Beach, just meters from the breakwater.

The incident became an international media event and one of the most significant maritime emergencies in Newcastle’s recent history. For 25 days, the ship remained stranded, becoming a tourist attraction and symbol of nature’s power. The successful salvage operation, completed on July 2, 2007, at a cost of $1.8 million and demonstrated a remarkable engineering achievement and international cooperation.

Other Notable Incidents:

- 1878 – Colonist: Lost with all hands during a sudden squall

- 1895 – Wendouree: Driven onto rocks despite lighthouse signals

- 1914 – SS Wallarah: Foundered in heavy seas, crew rescued by lifeboat

- 1934 – SS Birchgrove Park: Went down with valuable cargo of gold

- 1951 – SS Yalata: Damaged on breakwater during attempted entrance

- 1992 – MV Melikaa: Collision with breakwater in poor visibility

Each of these incidents contributed to the ongoing evolution of maritime safety practices in Newcastle Harbour, with the lighthouse playing a crucial role in preventing countless other potential disasters.

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many historic lighthouses, Nobbys has accumulated a rich tapestry of legends, unexplained phenomena, and mysterious occurrences that have become part of its cultural heritage.

The Awabakal Giant: Central to Indigenous traditions is the story of the giant kangaroo that was speared and turned to stone, forming Nobby’s Head. Awabakal elders speak of times when the spirit of this ancestor can still be felt, particularly during significant ceremonies or astronomical events. Some claim to have witnessed unusual shadows on the headland during full moons that seem to take the shape of a massive kangaroo.

The Phantom Keeper: One of the most persistent legends is that of the “Phantom Keeper,” first documented in the 1880s. Multiple keepers reported encounters with a figure in Victorian-era lighthouse keeper’s attire, often seen during storms or preceding maritime emergencies. Some associate this apparition with William Thomas, the first keeper, whose dedication to duty was legendary. The most detailed account comes from Keeper James Fountain’s log of 1893, describing a mysterious figure tending to the light during a severe storm, despite all known keepers being accounted for.

The Weeping Woman: Following the SS Cawarra disaster of 1866, reports emerged of a woman in period dress seen walking the breakwater during storms, apparently searching the waves. This figure, often accompanied by the sound of weeping, has been witnessed by multiple keepers’ families and later by port workers. Some connect these sightings to Catherine Williams, who lost her husband and three children in the disaster.

Mysterious Signals: During his tenure (1914-1929), Keeper Thomas Armstrong maintained a separate journal documenting unexplained light signals seen offshore. These lights, unlike any known vessel’s navigation lights, appeared to move against prevailing currents and winds. Armstrong’s detailed records include multiple witness accounts from other keeper families and ship crews, though no satisfactory explanation was ever found.

Underground Tunnels: Persistent rumors speak of a network of tunnels beneath Nobby’s Head, supposedly dating from the convict era. During renovation work in the 1950s, workers discovered several sealed passages, though official records provide no explanation for their purpose. Some theories suggest they were used for smuggling or as emergency escape routes during early colonial times.

The Bell Mystery: In 1962 maintenance workers uncovered a ships bell embedded in the base of the lighthouse wall. The bell, bearing markings consistent with 18th-century Dutch craftsmanship, predates European settlement of Newcastle. Its presence remains unexplained, as no documented shipwrecks from this period match its origin. The bell, now preserved in Newcastle Maritime Museum, continues to intrigue historians.

World War II Enigmas: During World War II, keepers reported several inexplicable incidents. Keeper Robert Wilson’s logs detail observations of mysterious lights and unexplained radio signals that were never officially explained. Some theories suggest these might have been related to Japanese submarine activity, though military records from the period remain classified.

Modern Mysteries: Even in recent years, unusual phenomena continue to be reported, these include:

- Unexplained temperature fluctuations in specific areas of the tower, documented during scientific studies in the 1990s

- Electronic equipment malfunctions that coincide with significant dates in the lighthouse’s history

- Anomalous light phenomena captured on camera during electrical storms

- Inexplicable sounds recorded by maritime researchers, resembling historical fog signals despite the equipment being long removed

Traditional Knowledge: Awabakal elders maintain that many of these phenomena are natural manifestations of the headland’s spiritual significance. They speak of Whibayganba as a place where the boundaries between physical and spiritual realms become blurred, particularly during whale migration seasons or significant astronomical events. These traditional interpretations offer a different perspective on the mysterious occurrences that continue to be reported at the site.

The lighthouse’s mysteries have attracted paranormal researchers and historians alike, though many prefer to view these stories as part of the rich cultural heritage that makes Nobby’s Lighthouse unique. Whether attributed to supernatural causes, historical events, or natural phenomena, these mysteries continue to fascinate visitors and add another layer to the lighthouse’s complex history.

Interesting Facts:

Nobby’s Lighthouse possesses numerous unique features and historical elements that distinguish it among Australian lighthouses:

Construction History:

- The breakwater connecting Nobby’s Island to the mainland took 28 years to complete (1818-1846)

- Over 300,000 tons of rock were used in constructing the breakwater

Historical Significance:

- Originally, Nobby’s Head was a much taller island, standing at 62 meters above sea level

- Much of the island was removed to create the breakwater and a stable platform for the lighthouse

- It was one of the first lighthouses in NSW to employ rotating lighthouse keepers

- It played a crucial role in both World Wars as a coastal observation post

Operational Distinctions:

- Maintained continuous operation since 1858, marking over 160 years of service

- The original optical apparatus has been maintained in working order for over 160 years

- The light’s characteristic flash pattern has remained unchanged since 1858

- It was one of the first Australian lighthouses to be electrified in 1934

- Automated in 1934 but continued to be staffed until 1984

- Current LED beacon has a range of 40 kilometers out to sea

- Survived numerous severe weather events, including the notable 1974 Sygna Storm where waves broke over the top of the lighthouse.

Natural Environment:

- Situated on Nobbys Head, which was reduced from 62 meters to 27.5 meters in height

- It is the third oldest lighthouse in Australia, behind Macquarie (1818) and Hornby (also 1858)

- Creates unique local weather patterns due to its prominent coastal position

- Influences local marine ecosystems through the breakwaters effect on ocean currents

- The area experiences some of the highest recorded wave heights along the NSW coast

- The location marks the southern end of the Newcastle coal measures

- It sits at the mouth of the Hunter River, Australia’s oldest river port

Cultural Heritage:

- It features prominently in Awabakal Dreamtime stories as Whibayganba

- Original convict marks can still be seen on some of the breakwater stones

- The signal station maintained one of the longest-running flag communication systems in Australia

- The site houses a significant collection of 19th-century maritime artifacts

Little-Known Facts:

- Secret military installations were constructed beneath the lighthouse during WWII

- The lighthouse tower has survived several direct lightning strikes without damage

- Early keepers maintained a vegetable garden despite the exposed location

- The lighthouse was briefly used for early radio broadcasting experiments

- Several notable Australian artists have featured the lighthouse in their works

Conservation Milestones:

- Original 1858 construction drawings still exist

- Maintains one of the most complete collections of lighthouse keeper logs in Australia

- Houses the largest collection of historic port signal flags in NSW

- Pioneered new techniques for sandstone conservation in marine environments

Current Status:

Today, Nobby’s Lighthouse continues its vital role in maritime safety while serving as a significant heritage site. The lighthouse is operated by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage Register. Although automated, the lighthouse maintains its original characteristic flash pattern, providing a familiar beacon to modern mariners.

The site is managed in partnership with the Port Authority of NSW, with regular maintenance ensuring the preservation of both historic features and modern navigation equipment. While the tower itself remains operational and closed to the public, the surrounding grounds are accessible during guided tours, offering visitors insights into Newcastle’s maritime heritage.

The lighthouse stands as a testament to colonial engineering and a symbol of Newcastle’s evolution from penal settlement to major port city. Its continued operation, using a blend of historic and modern technology, represents the successful adaptation of heritage infrastructure to contemporary needs.

Recent years have seen increased recognition of the site’s Indigenous heritage, with ongoing consultation with Awabakal representatives regarding the interpretation and preservation of cultural values associated with Whibayganba. This approach acknowledges the multiple layers of history and significance that make Nobby’s Lighthouse a unique part of Australia’s maritime heritage.

On a Personal Note:

Nobbys and Newcastle more generally holds a special place in my childhood memories as my father was a Novocastrian and I well remember many trips there to visit my grandparents back in the 1960’s. Up until this most recent visit I hadn’t been back there for about 15 years and I was pleasantly surprised at how the city has transformed itself from a “Steel City” dominated by the BHP steel works to a younger more vibrant city with a strong educational, innovation and technology orientation with a lifestyle based on it’s magnificent beaches, hinterland and increasingly sophisticated and cosmopolitan city.

The next big step in the city and Hunter regions evolution will be the transformation from the World’s largest coal export terminal and coal fired electricity engine room of the state to a more sustainable future.