Location:

Cape Byron Lighthouse is arguably Australia’s most iconic lighthouse and stands at the continents most easterly point, Cape Byron in northern New South Wales. The lighthouse is positioned on a dramatic headland rising 94 meters above sea level. The site offers commanding views over Byron Bay, the Pacific Ocean and the surrounding hinterland. Located in Cape Byron State Conservation Area approximately 3 kilometers east of Byron Bay township, this lighthouse marks a significant point where the southern warm currents meet cooler northern flows creating unique maritime conditions.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 28° 38’ S : Long: 153° 38’ E

First Lit: December 1, 1901 (Automated & Demanned 1989)

Tower height: 23m;

Focal Height: White 118m, Red 111m

Original Lens: 1st Order bivalve Henry-LePaute Fresnel lens on a mercury float.

Intensity: 2,200,000 candela

Range: White 27 nml; Red 8 nml

Characteristic: A White flash every 15 seconds [Fl W 15s ] and a Fixed Red Light visible from 148° -189°

Indigenous History:

The Bundjalung people of the Arakwal clan are the traditional custodians of the Byron Bay area. The cape was named “Cavvanbah” by the local Aboriginal people, meaning “meeting place.” The headland has significant cultural importance, with the area being used for ceremonies, food gathering, and as a lookout point for centuries before European settlement.

Julian Rocks, visible from the lighthouse, holds profound spiritual significance in Aboriginal culture. Known as “Nguthungulli” in traditional language, these rocks are central to local Dreaming stories. According to Bundjalung beliefs, Nguthungulli is the creator spirit who rests at Julian Rocks. The formation is said to have been created when an old warrior was struck by lightning while fishing from his canoe. Parts of his canoe broke away, forming what are now Julian Rocks.

The local Bundjalung people maintain that the area around the rocks is a men’s site of particular ceremonial significance. Traditional stories tell of the rocks being used as a boundary marker between different clan groups, and the surrounding waters were an important source of food. The deep waters around Julian Rocks were traditionally considered dangerous, with specific protocols and stories warning of the spiritual powers associated with the site.

The lighthouse site itself is part of a broader cultural landscape that includes significant dreaming tracks connecting the cape to the hinterland. These ancient pathways linked ceremonial grounds, food gathering areas, and places of spiritual significance, forming an intricate network of cultural sites that remain important to the Bundjalung people today.

that now bares their name

but this was considered to much as it was too far out of town. It’s now some of the most expensive property in Australia!

Colonial History:

Lieutenant James Cook named Cape Byron on May 15, 1770, after Admiral John Byron, grandfather of the poet Lord Byron and the first Englishman to circumnavigate the World. The Admiral had sailed past this promontory during his own voyage of discovery in HMS Dolphin in 1765. Cook noted in his journal the cape’s prominent position and the potential dangers of the surrounding reefs.

Early European settlement in the Byron Bay area began in the 1840s with the arrival of cedar getters. By the 1850s, a small maritime industry had developed, centered around what was then known as Cavvanbah. The waters around Cape Byron proved treacherous for shipping, with numerous vessels coming to grief on the rocky coastline and surrounding reefs. The increase in coastal trade led to repeated calls from ship owners and merchants for improved navigation aids. In 1873, in response to these concerns, a harbor pilot station was established at Byron Bay, though this proved insufficient for the growing maritime traffic. The construction of a jetty in the 1888 marked the area’s growing importance as a port for the timber trade, dairy products, and general cargo, and by 1890 Byron Bay was the second busiest port on the NSW coast outside of Sydney.

The decision to construct a lighthouse at Cape Byron was influenced by several factors. The increasing maritime traffic along the New South Wales coast in the late 19th century, particularly related to the timber trade and coastal steamers, made the need for a major light station urgent. The cape’s strategic position as the most easterly point of mainland Australia made it an obvious choice. Additionally, there was a significant gap in the chain of lights along the NSW coast between Smoky Cape and Point Danger that needed to be addressed.

In 1897, the NSW Government approved the construction of a lighthouse at Cape Byron. The selection of the site involved careful consideration of factors including visibility, elevation, and accessibility. The original plans called for a cast iron tower, similar to those used at other NSW locations, but this was later changed to precast concrete blocks, reflecting advancing construction techniques of the time.

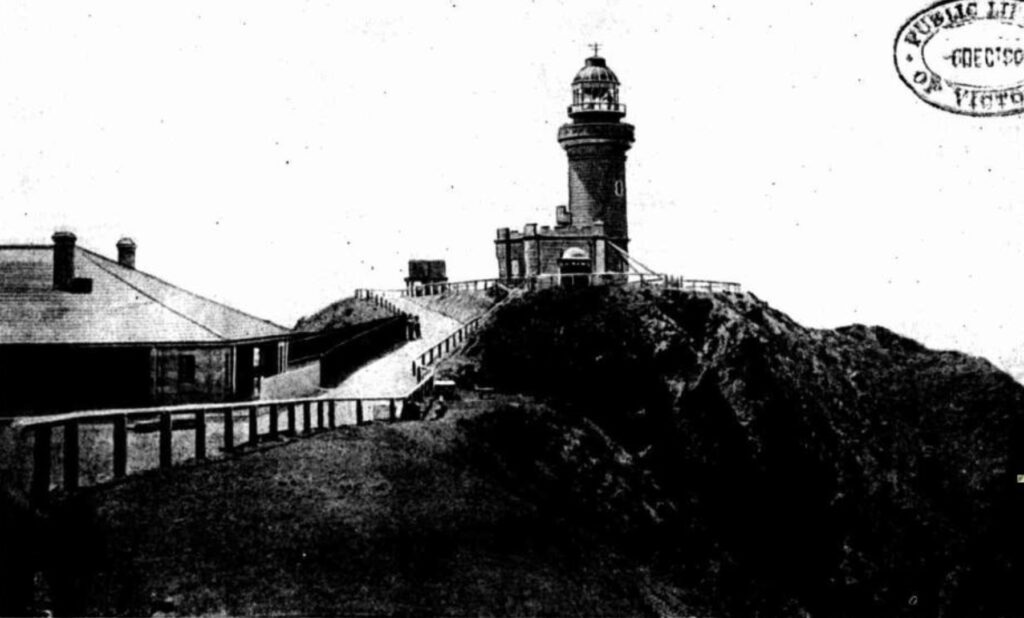

The lighthouse project was part of a larger colonial infrastructure development that included improved roads, telegraph connections, and port facilities in the Byron Bay area. The construction of the lighthouse complex, including three keepers’ cottages and associated buildings, represented a significant government investment in the region’s maritime safety infrastructure.

During the construction period (1899-1901), the project provided significant employment in the local area and spurred the development of Byron Bay township. Materials for the lighthouse were landed at the Byron Bay jetty and transported to the cape by bullock teams, a challenging undertaking given the steep terrain and often adverse weather conditions.

The Lighthouse:

Although the colony’s first lighthouse, the Macquarie Light at Sydney’s South Head was constructed in 1818 it was not until the mid 19th century that a considered uniform approach to lighthouse design was implemented across NSW.

As settlements were expanding and trade and coastal activity booming, the protection of life and property during its passage along the coast was becoming a critical issue for the colony. To address this, a powerful professional relationship was formed between Francis Hixson, Superintendent of Pilots, Lighthouses and Harbours and President of Marine Board of NSW (1863-1900), and James Barnet, Colonial Architect (1865–90), who together advocated for a “highway of lights” along the NSW coastline that demonstrated both architectural and functional consistency.

Responsible for the placement of navigational aids, Hixson was reported to have advocated for an ambitious system that would illuminate the coastline “like a street with lamps”. The decision to proceed with building the light was made at the end of the 1890s, and the site was levelled in October 1899.

The design and construction of these lighthouses and stations, however, fell to the Colonial Architect’s Office. Borrowing architectural themes established by Francis Greenway in his design of the Macquarie Light, Barnet designed a series of lighthouses that provided architectural consistency while responding to the complexities and often physical isolation of each site. Made up of a central lighthouse tower flanked by Head Keepers Quarters and Assistant Keepers Quarters, each lightstation precinct also incorporated buildings and facilities for the operation and maintenance of the light as well as the permanent accommodation of the lightkeepers and their families.

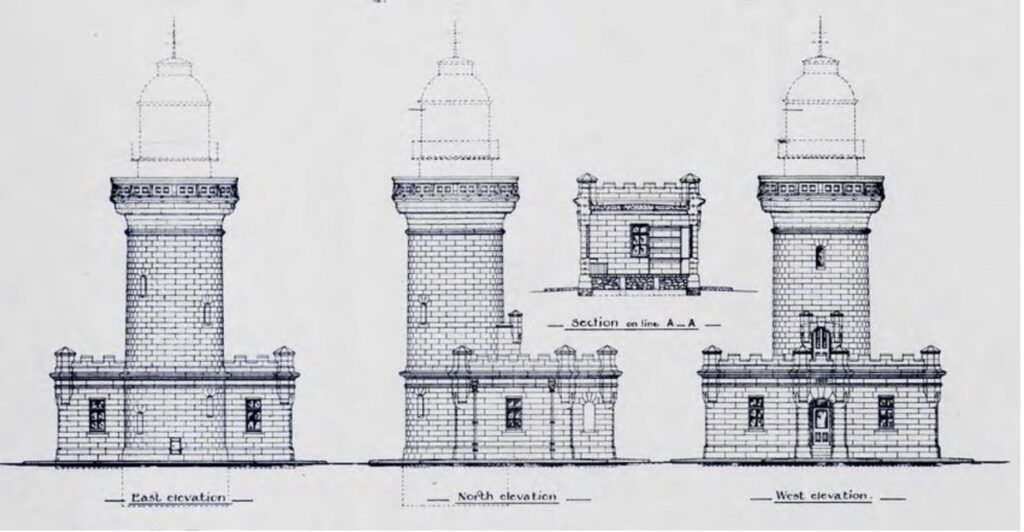

As Cape Byron was a significant headland with deep water at its base, it was considered to be easily visible to passing mariners and a lighthouse was not initially considered necessary. However, by the 1890s, as Cape Byron was the most northern location for a lighthouse in NSW, a station was promoted as being one of the last major structures to complete Hixson and Barnet’s string of coastal navigation lights along the NSW coastline. Although Barnet had retired in 1890 and the Marine Board of NSW had been disbanded, the design of the Cape Byron Lighthouse would be the first of Barnet’s successor Charles Assinder Harding, who also designed Norah Head Light and Point Perpendicular Light, in a style similar to Barnet’s. Harding was a specialist lighthouse architect for the Harbour and River Navigation Branch of the Public works Department and would bear some of the hallmarks of Barnett’s earlier designs.

Under the direction of Cecil W. Darley, Engineer-in-Chief, and continuing the strong architectural styling of the existing Barnet lighthouses, Harding designed a tower and precinct for the Cape Byron headland that was consistent with Hixson and Barnet’s vision but distinctive and contemporary in its use of developing technology and construction techniques.

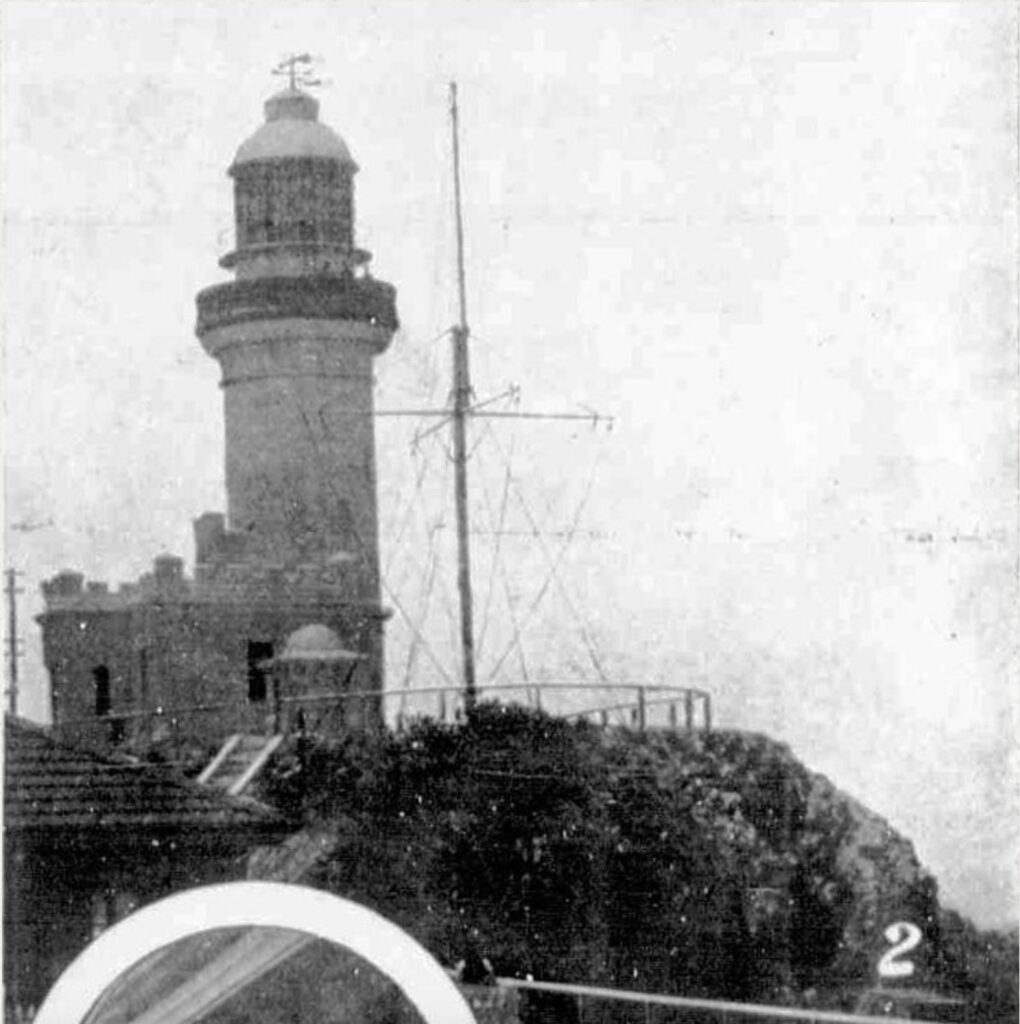

Taking advantage of the picturesque location and the prominence of the existing headland rising 93 metres above the Tasman Sea Harding designed a circular tapered tower, standing 72 feet (22 m) high, including the lantern. Ascending is done via an internal spiral concrete staircase with slate treads. It is topped by the iron floored lantern room. The lantern room has iron walls and a domed roof covered in sheet metal and surmounted by a wind vane and a ventilator. At the base of the tower, there is an entrance porch, lobby and two service rooms, all having crenellated parapet walls, painted white with blue trim on the bottom from the outside. The porch has a trachyte floor and steps, a cedar entrance door and etched glass panels and sidelights. The lobby has a tiled floor and trachyte steps, and the other rooms have asphalted floors and cedar windows. Housing at the site includes the head lighthouse keeper’s residence, and two assistant keeper’s cottages, signal station, store buildings and flagstaff.

With a budget of £ 18,000 allocated for the project in 1897, (£ 10,000 to contractors Mitchell and King, £ 8,000 for the apparatus and lantern house, and an additional £ 2,600 for the road from Byron Bay township), the narrow ridge of Cape Byron was cleared and levelled for the construction of the lighthouse, keepers cottages and associated structures in October 1899. Having cleared an access road to the site, a 40-strong workforce completed the lightstation precinct for its formal opening by the NSW Premier, John See on 1 December 1901. Having been fitted with a Henry-Lepaute feu eclair lightning flasher lens system on a mercury float mechanism with the light visible for 22 nautical miles, it was reported in newspapers of the time that there was not a finer station, nor one more picturesquely sited in NSW than the Cape Byron Lightstation.

The Buildings:

The Cape Byron Lighthouse demonstrates innovative construction techniques for its era, particularly in its use of concrete. The tower was constructed using precast concrete blocks, which was a relatively new building method in Australia at the turn of the 20th century. These blocks were manufactured on site using local sand and gravel mixed with imported cement.

The concrete blocks were cast in curved segments to form the cylindrical shape of the tower. Each block was carefully shaped to include a tongue and groove system that allowed them to interlock, enhancing the structural integrity of the tower. The blocks were laid in regular courses, with their joints staggered to provide additional strength. The thickness of the walls varies from approximately 0.75 meters at the base to 0.45 meters at the top.

The internal structure features a combination of materials. The central column supporting the spiral staircase is made of cast iron, while the stairs themselves are also cast iron, manufactured with a distinctive diamond pattern on the treads for grip. The landings at each level are supported by iron brackets built into the concrete walls.

The tower’s foundation is particularly robust, consisting of mass concrete poured into a circular excavation approximately 2 meters deep. This foundation was essential given the lighthouse’s exposed coastal location and the need to withstand severe weather conditions.

The tower takes a classic cylindrical form, tapering slightly as it ascends, with its smooth exterior walls punctuated by rectangular windows that spiral upward following the internal staircase.

The base of the tower features an entrance doorway, vestibule with offices on either side and the winding mechanism, counterweights and staircase in the centre of the tower. Inside, the internal staircase is an architectural marvel in its own right – a cast iron spiral staircase consisting of 104 steps. The stairs wind elegantly counterclockwise around a central column, with each tread featuring a distinctive geometric pattern that provided grip for the lighthouse keepers. The stairwell is illuminated by those strategically placed windows, which also offered ventilation for the keepers during their ascents.

At the summit of the tower sits the lantern room, an octagonal glass-enclosed chamber that houses the lighthouse’s optical apparatus. The lantern room is crowned with a domed copper roof, topped with a ventilator and lightning conductor. The glass panes of the lantern room are arranged in a distinctive diagonal pattern, set into robust brass frames designed to withstand severe weather conditions. A narrow external gallery encircles the lantern room, protected by metal railings, which allowed keepers to clean the exterior glass and conduct maintenance.

Construction began in 1899 under the direction of Charles Harding, who was contracted to build both the tower and associated buildings for £10,900. The lighthouse was officially opened on 1 December 1901 by the NSW Premier, John See.

The Tower: The Cape Byron Lighthouse is constructed in the Classical Revival style typical of Colonial Architect James Barnet’s work, though it was actually designed by his successor, Charles Assinder Harding. The tower stands 22 meters high and is constructed of precast concrete blocks, making it one of the first lighthouses in Australia to use this building technique.

The tower features a distinctive white concrete construction with a graceful taper from base to top. Eight massive buttresses support the basement section, giving the structure additional stability against the strong coastal winds that buffet the headland.

Internal Features: The internal structure includes a cast-iron spiral staircase of 109 steps leading to the lantern room. The walls are exceptionally thick at the base, tapering as they rise, providing both strength and stability. The lighthouse incorporated innovative ventilation systems designed to handle the humid coastal conditions.

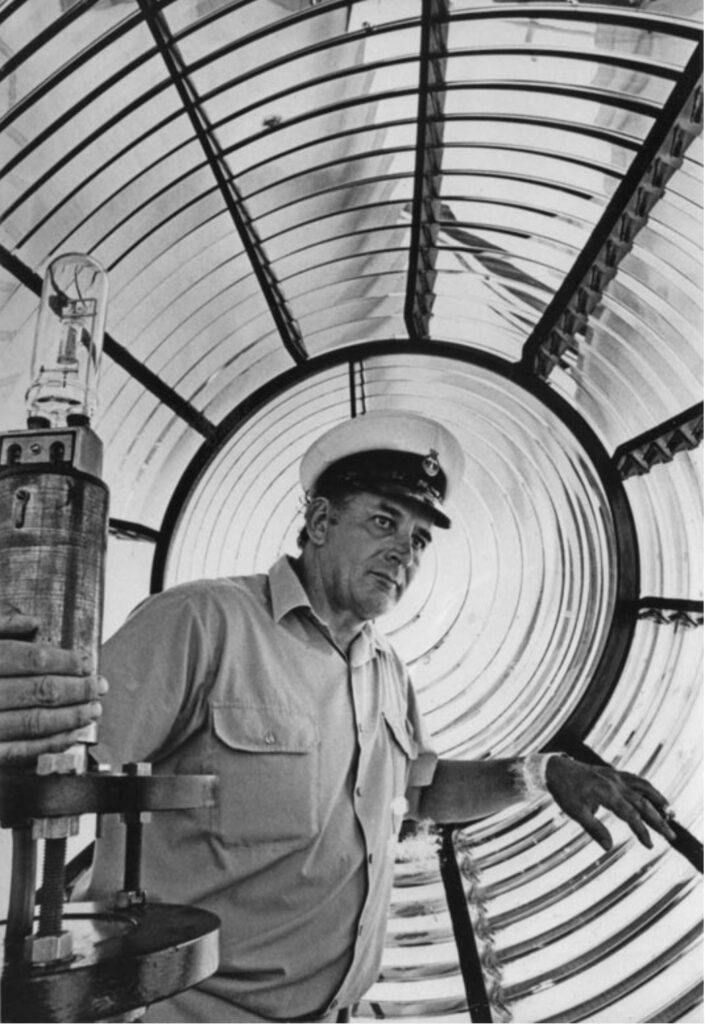

Lantern Room: The lantern room houses the original First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens assembly, which remains in operation today. The optical apparatus consists of a massive crystal lens floating in a mercury bath, allowing for smooth rotation despite its substantial weight. The lens is one of the largest of its kind ever installed in Australia.

Today the lighthouse contains a museum and the significant moveable heritage items including the 38-centimetre (15 in) Chance Bros & Co red sector light (1889) on a cast iron pedestal; the original curved timber desk (1899-1901) and the clockwork lantern winch (1901).

Technical Details:

The lens now in use is the original 1st Order bivalve Henry-LePaute Fresnel lens. The 2m diameter lens, weighing 8 tonnes contains 760 pieces of highly polished prismatic glass, floating in a 7 356 kg bath of mercury. It was the first lighthouse in Australia with a mercury float mechanism. The mechanism is rotating also during the day to reduce the risk of fire from the sun’s rays. It is the only Henry-LePaute apparatus in Australia.

The original light source was a concentric six wick kerosene burner with an intensity of 145,000 cd. This was replaced in 1922 by a vapourised kerosene mantle burner with an intensity of 500,000 cd.

In 1922 an improved apparatus was installed, doubling the power to 1,000,000 cd. In 1956 the light was electrified, the clock mechanism was replaced by an electric motor, and the light source was replaced with a 1000 watt 120 volt tungsten-halogen lamp with an intensity of 2,200,000 cd, fed from the mains electricity with a 2.5 KVA backup diesel alternator. At that time, the keeper staff was reduced from three to two.

The station was fully automated in 1989, and the last lighthouse keeper departed.

The light characteristic shown is a white flash every 15 seconds (Fl.W. 15s). The tower also displays a red, short ranged, continuous light (F.R.) to the northeast, covering Julian Rocks and the nearby reefs. The red light is emitted at a lower focal plain.

Keepers of the Light:

The Cape Byron Lighthouse was initially manned by a Head Keeper and two Assistant Keepers who lived on the lightstation with their respective families but after control of lighthouses in NSW was transferred to the Australian Government in 1915 lightstations were gradually but progressively automated. Cape Byron Lightstation was converted from vaporised kerosene to electricity in 1959 but as a human presence was considered beneficial at the site, coupled with the proximity of the station to the Byron Bay township, light keepers continued to operate the station until 1989.

Head Keepers:

- William Warren (1901-1916)

- Herbert Reeves (1916-1923)

- Thomas Smith (1923-1934)

- Frederick Cook (1934-1949)

- James Paterson (1949-1956)

- Percy Mitchell (1952-1965):

- The Thisleton family maintained three generations of keepers

- Peter Bailey was the last headkeeper at Cape Byron Lighthouse, serving from 1980–1989.

As automation technology advanced, the number of keepers was gradually reduced. By the 1980s, only one keeper remained on site. The last keeper, Gordon Clark (1983-1989), oversaw the transition to full automation in 1989, marking the end of 88 years of manned operation at Cape Byron.

Many former keeper families maintain connections with Cape Byron, and their descendants regularly visit the station. The keepers’ detailed logs and photographs have proved invaluable for historical research and maintenance of the lighthouse. Their stories and experiences are now preserved in the lighthouse museum, providing visitors with insights into this unique way of life that has now passed into history.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

The waters around Cape Byron have been witness to numerous maritime tragedies, with the cape’s position and surrounding reefs proving treacherous for shipping since colonial times. The combination of strong currents, hidden reefs, and unpredictable weather has resulted in many vessels coming to grief in these waters.

There were a litany of shipwrecks in the years preceding the construction of the lighthouse due to the fact there are a number of large rivers, such as the Tweed, Richmond and Clarence Rivers stretching north from Byron Bay to the Queensland border and south to Coffs Harbour. At the time of European settlement these rivers were navigable and some could support river ports. However, there were no natural safe coastal harbours or easy refuge in storms. Ships traveling along this coast carrying cargo and passengers were required to risk crossing the shifting sandbars at the mouth of these rivers to load and unload or to do this from the beaches. In bad weather and storms ships could attempt to “ride it out” or to shelter in any lee available or try to run up the rivers. Byron Bay was the best deep water shelter along this stretch of coast but provided no safe harbour from gales from the north or west.

To compound the difficulty for the increasing number of ships sailing along and servicing this stretch of coast it was not until the 1880’s that accurate marine charts became available and navigation lights were installed. There were no roads or railways and shipping was the only transport option for this part of the world until the mid-1890’s.

This resulted in many “narrow escapes”, numerous groundings, many ships being wrecked and some true disasters along this stretch of coast. Up until the Cape Byron lighthouse began operation in December 1901 the records of the NSW Heritage Office show details of at least 21 ships lost around Cape Byron, including:

- 1846. The Coolangatta, a wooden schooner, was wrecked on the beach north of the lighthouse. This early wreck highlighted the dangers of the coast and influenced later decisions about maritime safety in the region.

- 1849 the Swift ran ashore at Brunswick River after being blown south from the Tweed River. Five lives were lost but two passengers miraculously survived. They were cut from the overturned hull with an axe after people walking along the beach recovered from their surprise when their knocks on the upturned hull stranded on the beach were answered by the two trapped inside.

- 1864 the Volunteer was wrecked on Cape Byron in a gale with all lives lost and its cargo of tallow was washed up on the shore.

- 1870. The City of Sydney came to grief on Julian Rocks demonstrating the hazards posed by this offshore reef even in clear conditions.

- 1875 the Andrew Fenwick with a cargo of flour was wrecked on a beach just north of Cape Byron and the Miranda was wrecked at Cape Byron.

- 1876 the William was wrecked in a gale near Byron Bay sailing to load cedar here and the Brilliant was wrecked at Cape Byron but subsequently salvaged only to be wrecked and abandoned on the beach south of Brunswick Heads in 1884.

- 1879 the Inglis was lost when loading timber off the beach south of Brunswick River and was driven ashore at Byron Bay.

- 1886 the Jane was washed ashore at Tallow Beach in a gale while waiting to load timber and the Condong foundered near Cape Byron

- 1889 five ships, Agnes, Bannockburn, Fawn, Hastings and Spurwing were blown ashore on Belongil Beach during an extreme storm. Of these only the Agnes was refloated; the others being wrecks. The anchor of the Fawn has been recovered and is on display in town.

- 1890 the Agnes was wrecked again this time north of the Brunswick River with eight lives lost.

- 1891 the Anne Theresa sprang a leak after bumping the ground and forced to run aground at Byron Bay.

- 1893 the Tweed carrying a load of supplies for the new railway line being built at Byron Bay was wrecked on the shore at Byron Bay when seas disabled its rudder.

- 1894. The wooden schooner Volunteer was lost off Cape Byron after being caught in a fierce storm that drove her onto the rocks despite the crew’s desperate efforts to save her.

- 1894 the Tuggerah was wrecked in Byron Bay when its anchors failed to hold.

That there were other unrecorded wrecks is evidenced by the discovery of an old wooden rudder buried six metres under the sand at the southern end of Tallow Beach by sand miners in 1965. This discovery made headlines around the world when initial carbon dating of timber from the wreck yielded an age between 1450’s and 1660’s with a most likely age of 1551 meaning it predated Captain Cook’s discovery voyage of 1770. This date was later shown to be incorrect and the wreck to be from the 1880’s.

Even after the lighthouse’s construction, the area has continued to claim many vessels including:

The most significant shipwreck to occur in Byron Bay was that of the 2000 tonne Wollongbar on 14 May 1921. This ship was built for the North Coast Steamship Navigation Company in 1911 to provide regular scheduled passenger and freight transport between Sydney and Byron Bay. Early in the afternoon of Saturday 14 May 1921 the Wollongbar was tied up alongside the old jetty about 200 metres offshore. It had finished loading cargo and was ready to board crew and passengers in time to depart for Sydney at 5.00pm. However just before embarkation a combination of large waves, strong winds and low tide resulted in the ship’s keel bumping on the seabed. Recognising the jeopardy the captain cast off to head into deeper, safer water. However, as the moorings were freed the ship grounded on a sand bar and turned broadside to the large waves. The captain valiantly tried to recover course and several times got the vessel’s bow turned back toward the sea but each time the ship encountered the sandbar, stalled, and was pushed closer to land. Eventually the wind, waves and current prevailed and the ship stranded in the surf on Belongil Beach. Despite several attempts to re-float the Wollongbar none was successful and the wreck was sold for salvage. The abandoned hull, boilers, rudder bar and tiller were all that was left. The rudder bar and boilers are often visible, and in between large storm waves the hull can be glimpsed. No lives were lost but for Byron Bay a crucial link with the outside world was gone. The outline of the hull can still be seen through calm seas from the air.

On 25 August 1939 as the 544-ton steamer Tyalgum got into difficulty off Cape Byron on a voyage from Sydney to the Tweed river and was taken in tow by the tug Undaunted, however the steamer grounded on a reef off Flagstaff Beach near the entrance to the Tweed river and water flooded into the damaged hull. The crew of seventeen was taken off and the ship was abandoned and left to it’s fate.

The SS Wollongbar II was perhaps the most famous maritime tragedy in the area. On April 29, 1943, the vessel was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-180 approximately 4 nautical miles east of Byron Bay. The ship sank within minutes with the loss of 32 lives. Only five crew members survived. Parts of the wreck still lie on the seabed and are occasionally exposed during strong storms.

The MV Limerick met a similar fate during WWII. On April 26, 1943, just three days before the Wollongbar II incident, she was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-177 off Cape Byron. The vessel sank with the loss of two lives. The proximity of these wartime incidents led to increased coastal defenses around Cape Byron.

There was one other ship sunk in Byron Bay during WWII, the Tassie III, a 120 tonne steel ship requisitioned by the US Army and carrying condemned ammunition. It came into Byron Bay on the night of 8 June 1945 to anchor from a storm. During the night the ship dragged its anchor and beached. On the following high tide the ship re-floated and washed up against the “old jetty”. As the weather became rougher the Tassie III broke some of the jetty piles and the stumps of the piles penetrated the hull and the vessel sank.

Recent decades have seen several fishing trawler incidents, including the capsize of the Kay-D in 1975 and the loss of the Barbara Jane in 1992. These modern tragedies often occurred despite advanced navigation equipment and the lighthouse’s powerful beam.

The waters around Cape Byron are particularly dangerous during East Coast Lows, when strong currents, large swells, and poor visibility combine to create hazardous conditions. Several recreational vessels and yachts have required rescue in recent years, with the local Marine Rescue unit frequently called into action.

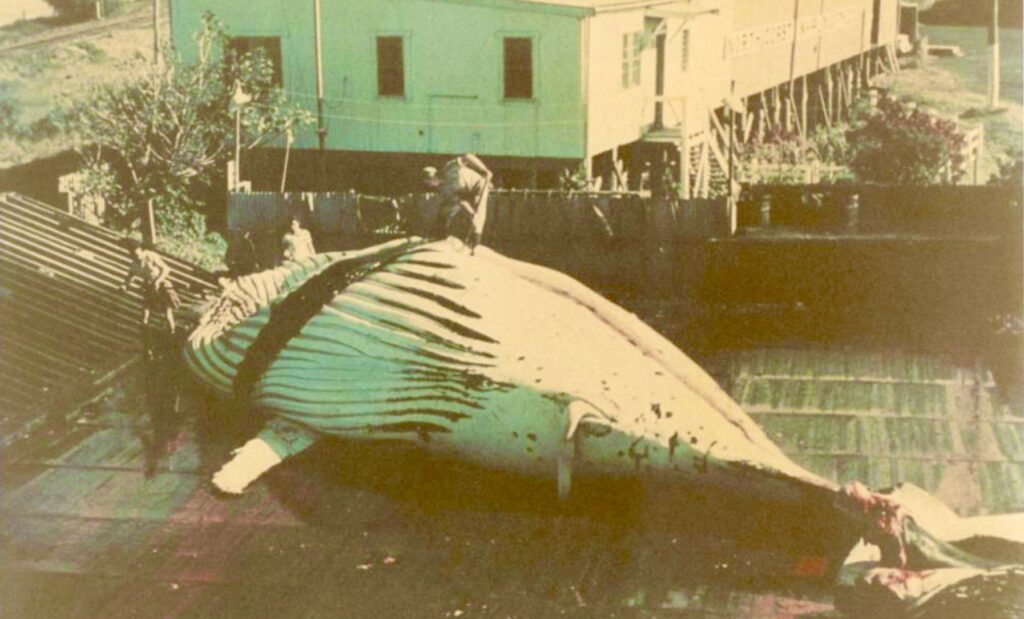

Cape Byron lighthouse witnessed a particularly dark chapter in Byron Bay’s history from July 1954 until October 1962 when The Byron Whaling Company operated a commercial whaling fleet and factory in the bay. In conjunction with other whaling stations along the NSW coast this activity decimated the east coast population of humpback whales due to over hunting. The industry collapsed and was ultimately outlawed in 1966 and the migrating humpback population have since recovered from fewer than 5,000 to more than 35,000 whales passing Cape Byron each season.

Near the lighthouse itself, the cliff areas have witnessed numerous land-based tragedies including a terrible event on 4th September, 1952 when a family of six were killed when their car plunged from the carpark 90m down the cliff into the sea. This led to improved traffic management and safety barriers but accidents continue to happen on the one lane winding access road and congested car park. Sadly there have been many other fatalities and serious injuries on the cliffs and walkways surrounding the headland. As recently as May 2019 the unresolved disappearance and presumed death of the young Belgian tourist Theo Hayez at or near Cape Byron is the latest chapter in it’s tragic history.

It seems ironic that such a beautiful place could have witnessed so much tragedy! Take Care!

Myths & Mysteries:

Cape Byron and its lighthouse have accumulated a rich tapestry of legends, mysterious occurrences, and unexplained phenomena over the years, blending Indigenous spirituality, maritime folklore, and modern mysteries.

Several lighthouse keepers reported unexplained occurrences during their tenure. In the 1920s, keeper John Kelly documented strange lights appearing to dance on the horizon, moving in ways that defied the known patterns of shipping traffic. These lights were seen repeatedly over several months but were never explained.

The second assistant keeper’s cottage became known for inexplicable cold spots and the sound of footsteps on the wooden floors, even after the building was automated. Some attribute these phenomena to the spirit of a keeper who died suddenly while on duty in 1914, though official records are unclear about this incident.

Local fishermen tell of a “ghost ship” occasionally seen in the early morning mist around Julian Rocks. The vessel is described as a nineteenth-century schooner, complete with full sail, though it vanishes when approached. Some connect these sightings to the 1870 wreck of the City of Sydney.

During electrical storms, observers have reported seeing St. Elmo’s Fire dancing around the lighthouse tower, creating spectacular displays that have become part of local folklore. These natural electrical phenomena have contributed to the lighthouse’s mysterious reputation.

Beyond the traditional Indigenous beliefs about Nguthungulli at Julian Rocks, the cape has attracted various spiritual associations. The lighthouse’s position as the first place on mainland Australia to see the sun each day has led to it becoming a focus for New Age ceremonies and spiritual gatherings, particularly during solstices and equinoxes.

Local legend speaks of a “guardian spirit” of the cape, said to manifest as a cool breeze on still days, warning of approaching storms. Some longtime residents claim this phenomenon has saved lives by alerting fishermen to dangerous weather changes.

In the 1960s, several unexplained radio disturbances were recorded at the lighthouse, with the keeper’s communications equipment picking up what were described as “unearthly” sounds. These incidents coincided with unusual light phenomena observed offshore, though no official explanation was ever provided.

The area around the lighthouse has become known for compass irregularities, with several boats reporting navigation equipment malfunctions in the vicinity. While some attribute this to natural magnetic anomalies in the rocky headland, others point to more mysterious explanations.

During the full moon, observers have reported seeing unusual bioluminescence patterns in the ocean around the cape, different from the typical phosphorescence seen in these waters. Marine biologists have yet to fully explain these occurrences.

Interesting Facts:

Cape Byron Lighthouse is the most powerful lighthouse in Australia with a range of 27 nautical miles. Its location on Australia’s most easterly point makes it a significant tourist attraction, with over 500,000 visitors annually. The lighthouse complex is one of the most complete light stations surviving in Australia, with all its original buildings intact.

The site offers exceptional opportunities for whale watching during the annual migration seasons (June-July and September-November). The lighthouse precinct is part of the Cape Byron State Conservation Area and is managed by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Current Status:

Cape Byron Lighthouse remains an active aid to navigation, managed by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The lighthouse precinct includes a maritime museum in the former keeper’s quarters, and guided tours of the lighthouse are available daily. The lighthouse continues to play a crucial role in maritime safety while serving as an important heritage site and tourist attraction.

I’m extremely impressed along with your writing talents as neatly as with the format on your blog. Is that this a paid theme or did you customize it your self? Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is rare to look a nice blog like this one today!