Location:

Double Island Point Lighthouse is located at the northern extremity of Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, perched atop a prominent headland approximately 140 kilometres north of Brisbane. The lighthouse commands a spectacular position 89 meters above sea level, offering expansive views from Noosa Heads to Fraser Island (K’gari). The name “Double Island” comes from the headland’s appearance from the sea, where it resembles an island with two hills.

The lighthouse’s strategic location marks a significant turning point for coastal shipping, where vessels must change course to navigate around the jutting headland. The site experiences substantial weather events typical of the Queensland coast, including seasonal cyclones and severe storms, while also being exposed to strong southeasterly winds that can exceed 100 km/h during winter months.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 25° 56′ 25″ S Long: 153° 11′ 23″ E

First Exhibited: 11.9.1884 (Automated & Demanned 1992)

Tower height: 12m

Focal Height: 96m above MSL

Original Lens: Third Order Chance Brothers Dioptric lens

Intensity: 1,000,000 candela (as of 1980), now 48,430 cd

Range: 26 nautical miles (as of 1980), now 17 nml

Characteristic: One white flash every 7.5 seconds [Fl.W. 7.5s]

Indigenous History:

The Kabi Kabi (Gubbi Gubbi) people are the Traditional Owners of the Double Island Point area, known to them as “Gharr” meaning “young whale.” For countless generations, they maintained deep connections with this significant coastal landscape, using the elevated headland as an important lookout point for whale watching and monitoring seasonal changes.

Archaeological evidence indicates continuous occupation spanning thousands of years, with significant shell middens and stone tool scatters found throughout the area. The headland played a crucial role in Indigenous coastal resource management, offering commanding views of both the northern and southern approaches, essential for monitoring fish movements and weather patterns.

The Kabi Kabi people developed sophisticated knowledge systems around the area’s marine resources, weather patterns, and seasonal changes. Their traditional stories speak of the headland’s role in ceremonial practices, particularly during whale migration seasons when the point served as an ideal vantage point for spotting these culturally significant creatures.

Today, the Kabi Kabi people maintain their connection to country through various cultural practices and involvement in the area’s management, working in partnership with government agencies to protect and interpret the rich cultural heritage of Double Island Point.

Colonial History:

European maritime engagement with Double Island Point began with Lieutenant James Cook, who named the headland during his voyage along the east coast in 1770. The name was inspired by the twin peaks of the headland which, when viewed from the sea, appeared as two islands. Cook noted in his journal the strategic importance of this prominent landmark for coastal navigation.

The area gained increasing significance following:

- The establishment of the Gympie goldfields in 1867

- The development of Maryborough as a major port

- The growth of coastal trading along the Queensland coast

- The establishment of timber-getting operations in the Wide Bay region

The Lighthouse:

The colony of Queensland was formed in 1859. In 1862 the Queensland government appointed the first Portmaster, Commander George Poynter Heath. However, it was only in 1864 that two committees were appointed to deal with the issue of coastal lighthouses. One of the locations indicated by these committees as a possible suitable site was Double Island Point. However, it was to take almost two decades until the Queensland Government took action upon this recommendation.

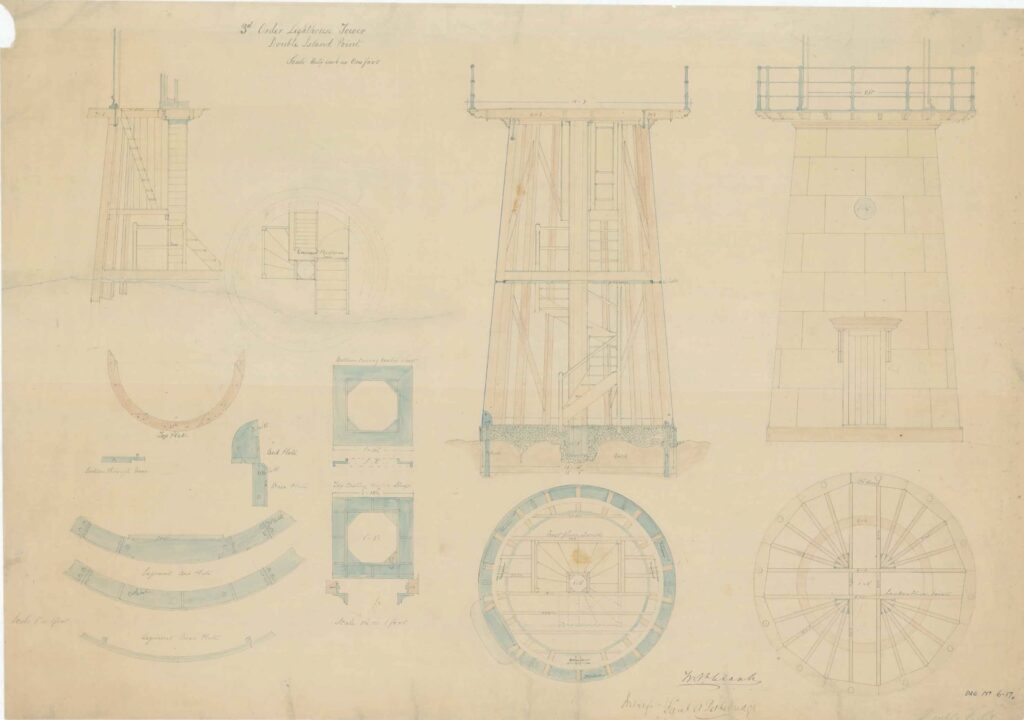

In 1881 Heath made a further report to the Parliament stating the need for the lighthouse. In 1883 he made a visit to the island and realised that the originally planned location, halfway up the point, would result in a light that would not be visible to the north. He advised that the lighthouse will be constructed at the summit of the point, with a 3rd Order light, a more powerful light than originally planned, and advise which was accepted. Plans were made by the Queensland Colonial Architect’s Office, and at the end of June 1883 tenders were called for the construction of the lighthouse and lightkeepers cottages, for both Double Island Point Light and Sandy Cape Light. The contract for both lightstations, for the cost of £ 6,900, was awarded to W. P. Clark, who already constructed Queensland’s first lighthouse since Queensland’s formation, Bustard Head in 1868.

Originally the light was to be constructed only halfway up the point but upon closer inspection it was realised that the light would not be visible toward the North. It was decided that a more powerful light at the top of the point would be more effective.

The light was first fitted with an oil burner and revolving panels. In 1923, it was converted to an incandescent mantle using vapourised kerosene, thus increasing it’s power to 100,000 Candelas.

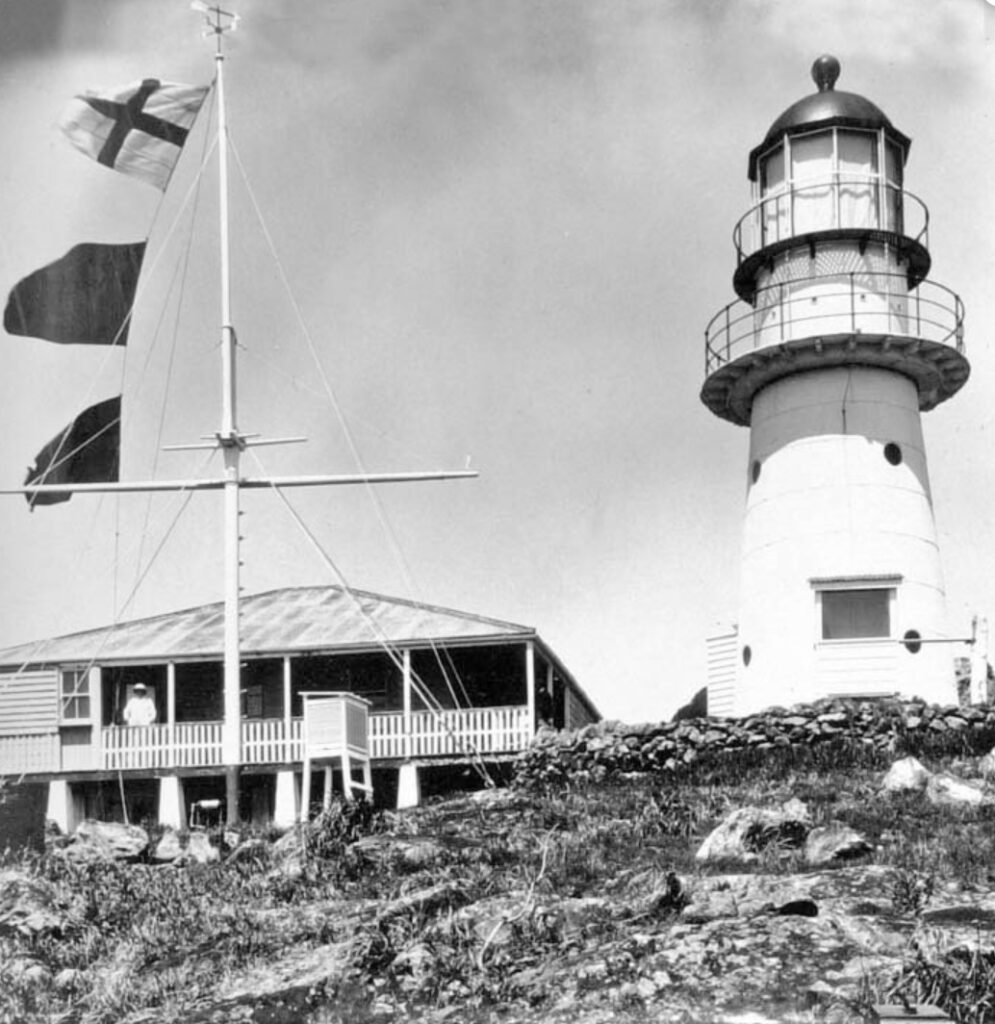

In 1925, the light was further upgraded by fitting an revolving lens that floated in a mercury bath. The next conversion was to 110v DC electricity giving a powerful 750,000 candelas. During this period the 3 original cottages were replaced by 2 new ones further down the hill.

In 1980, bulk fuel tanks were installed and the light was converted to 240v AC power, and in 1992, the light was converted to solar power and demanned.

The Buildings:

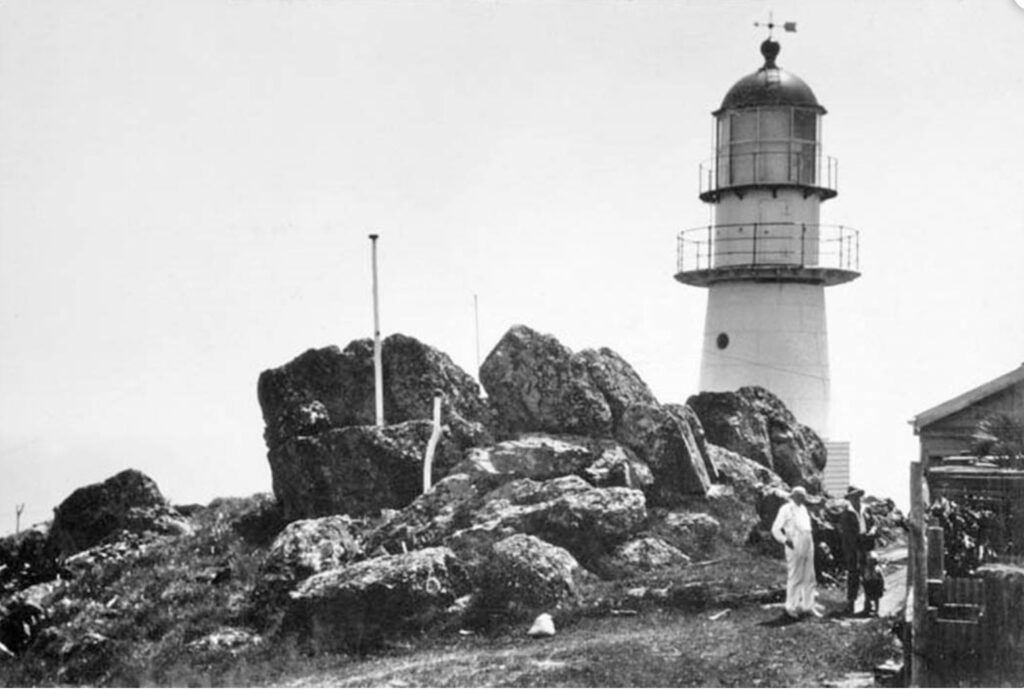

The lighthouse is typical for Queensland, made of timber frameclad with galvanized iron plates, painted white with a red dome. It is surmounted by an original Chance Brothers lantern with a modern VRB-25 self-contained rotating beacon mounted inside. It is surrounded by several auxiliary structures. The two lighthouse keepers’ cottages, hardwood framed and sheeted with asbestos cement, are at a lower level, with a few other buildings.

The structures at the station are divided into two clusters, one around the lighthouse and the other near the cottages.

The lighthouse was first exhibited on 11 September 1884, the eighteenth to be constructed by the Queensland Government. The original lamp was an oil wick burner with an intensity of 13,000 cd. It was fixed, with revolving panels. Three lighthouse keeper cottages were also constructed, originally located near the lighthouse. A schoolhouse was also established at the point at the same time, which was active until 1922.

South of the cottages is the grave of Fanny Byrn, wife of George Byrne who was the head lightkeeper from February 1886 until July 1900. It is surrounded by a picket fence and marked with a marble headstone.

Technical Details:

The optical system at Double Island Point represented a significant advancement in lighthouse technology. The Third Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, while smaller than Sandy Cape’s First Order lens, was selected for its superior efficiency and suitability to the site’s requirements.

Original Optical Apparatus (1884): The lens assembly stands 1.8 meters tall and consists of:

- A central drum with catadioptric prism panels

- Upper and lower catadioptric prisms

- A hand-ground glass prismatic array

- Bronze framework with precise adjustment capabilities

- A clockwork rotation mechanism with gravity drive

The light source evolved through several technologies:

- 1884-1923: Kerosene wick lamp

- Initially a 4-wick configuration

- Later upgraded to a 6-wick system

- Consumed approximately 0.8 liters of kerosene per hour

- 1923-1960: Pressure kerosene system

- 55mm incandescent mantle

- Automated pressure regulation

- Significantly increased light intensity

- 1960-1992: Electric incandescent system

- 1000W tungsten filament lamp

- Automatic lamp changer

- Backup power system

- 1992-Present: Solar-powered system

- Modern halogen lamp

- Photovoltaic array

- Battery storage system

- Automated monitoring and control

Keepers of the Light:

For over a century, Double Island Point Lighthouse was home to a succession of dedicated keepers and their families, each contributing to the rich tapestry of the station’s history. Their stories reflect not just the technical demands of lighthouse keeping, but the unique challenges and rewards of life in this isolated coastal community.

Alexander Byrne (1884-1898), the first keeper, established the foundation for lighthouse operations at Double Island Point. His methodical approach to record-keeping provided invaluable insights into early lighthouse operations. Byrne’s comprehensive journals detail the daily challenges of establishing a new lighthouse station, from developing maintenance routines to creating sustainable living practices. His wife Mary emerged as a significant figure in the station’s history, becoming known for her botanical expertise. She established extensive gardens that helped sustain the lighthouse community, while meticulously documenting local flora. Her botanical drawings and notes, preserved in the Queensland State Archives, provide valuable information about the region’s natural history.

William Simpson (1898-1916) transformed the technical operations of the station. His engineering background proved invaluable during the transition to more sophisticated lighting systems. Simpson’s detailed maintenance records and technical drawings continue to provide valuable information for modern lighthouse preservation. His innovations included designing a more efficient water collection system and developing new methods for maintaining the optical apparatus in the harsh coastal environment. Simpson’s wife Elizabeth established the station’s first school room, providing education for both their children and those of assistant keepers.

Thomas Kenna’s tenure (1916-1927) coincided with World War I and its aftermath, bringing new challenges and responsibilities to the lighthouse. Kenna developed innovative signaling systems for communicating with passing vessels and maintained detailed records of shipping movements that proved valuable for naval intelligence. His wife Sarah became known for her medical skills, treating not only lighthouse families but also shipwrecked sailors and local fishermen who sought help at the station.

The Stephenson family’s period (1927-1942) represents one of the longest continuous tenures at the lighthouse. James Stephenson, his wife Margaret, and their five children became deeply connected to Double Island Point. Their extensive correspondence provides vivid descriptions of family life at the station, including chronicles of Christmas celebrations, improvised entertainment, and the challenges of raising children in isolation. Margaret’s detailed household accounts offer insights into the practical aspects of lighthouse life, from managing supplies to maintaining social connections through correspondence.

The war years under Harold Weber (1942-1956) brought increased responsibilities and heightened vigilance. Weber coordinated closely with military authorities, maintaining the light while adhering to strict blackout protocols when enemy vessels were suspected nearby. His careful documentation of unusual maritime activity contributed to coastal defense efforts. Weber’s daughter Alice maintained a detailed diary that provides rare insights into the impact of wartime restrictions on lighthouse life.

Robert McKay’s time as keeper (1956-1973) saw significant technological transitions. His background in electrical engineering proved valuable during the station’s modernization. McKay documented the change from kerosene to electric operation, while working to preserve traditional lighthouse practices. His wife Jean established a weather monitoring program that provided valuable data for the Bureau of Meteorology.

The final traditional keeper, David Thompson (1973-1992), guided the station through its final years of manned operation. Thompson recognized the historical significance of this transition period and worked to document traditional practices before automation. His efforts to preserve the station’s heritage, including collecting oral histories from former keepers and their families, helped ensure that the human story of Double Island Point would not be lost.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

The waters around Double Island Point have witnessed numerous maritime disasters, each contributing to the lighthouse’s history and the evolution of maritime safety practices in the region. The challenging geography, where vessels must make significant course changes, combined with seasonal weather patterns, has created particularly hazardous conditions that have claimed vessels ranging from small fishing boats to ocean-going steamers.

Early Disasters (Pre-Lighthouse): The need for a lighthouse at Double Island Point was tragically demonstrated by several shipwrecks in the decades before its construction. The loss of the schooner Salamander in 1864, with all hands, highlighted the dangers of navigating this stretch of coast at night or in poor visibility. The wreck of the Sterling in 1874, while attempting to round the point in heavy weather, added urgency to calls for a navigation aid.

Notable Incidents After Construction: The wreck of the SS Dickey in 1886, just two years after the lighthouse began operation, demonstrated both the hazards of the point and the importance of the new light. Despite the lighthouse’s warning beam, the vessel struck a reef in heavy weather. Keeper Byrne and his assistants coordinated a dramatic rescue, working through the night with local fishing boats to save all crew members. This incident led to improved protocols for fog signaling and the establishment of an auxiliary signal station.

The 1891 loss of the barque Espirito Santo highlighted the challenges of navigating the point during tropical storms. Though the lighthouse helped guide rescue vessels to the scene, eleven crew members were lost. This tragedy led to improvements in weather warning systems and the installation of additional signaling equipment at the station.

The steamer Bunyip incident of 1907 demonstrated the value of the lighthouse in rescue operations. When the vessel lost power near the point, Keeper Simpson’s precise position reporting and signaling helped tugs from Maryborough locate and rescue the stricken vessel before it could drift onto nearby reefs.

Wartime Incidents: During World War II, the area saw increased maritime activity and associated dangers. In 1943, a small convoy of coastal vessels came under attack from Japanese submarines near the point. The lighthouse played a crucial role in guiding rescue vessels to survivors, while maintaining blackout protocols when enemy vessels were suspected nearby. Keeper Weber’s logs provide detailed accounts of several dramatic rescues during this period.

Modern Era: The post-war period brought new types of maritime incidents, often involving smaller vessels and recreational craft. The 1962 foundering of the fishing trawler Sea Bird demonstrated the continuing importance of the lighthouse in modern rescue operations. Keeper McKay’s quick action in alerting authorities and coordinating with rescue vessels helped save the crew of four.

A particularly dramatic incident occurred during Cyclone Dinah in 1967, when the lighthouse became a refuge for several fishing boats seeking shelter from the storm. Keeper McKay and his family provided emergency accommodation for twelve stranded fishermen for three days until the weather moderated.

The yacht Spirit of Youth incident in 1985 highlighted the evolving role of the lighthouse in modern maritime safety. When the vessel lost all power and navigation equipment in rough seas, the lighthouse’s beam provided the only reliable reference point, allowing the crew to maintain position until rescue vessels arrived.

Recent Events: Even in the era of GPS and modern navigation equipment, Double Island Point continues to pose challenges for vessels. The grounding of the catamaran Wave Dancer in 2008 and the rescue of the fishing trawler Northern Belle in 2015 demonstrate the continuing importance of the lighthouse as a physical guardian of this treacherous stretch of coast.

Each of these incidents has contributed to improvements in maritime safety practices and equipment at Double Island Point, while underscoring the vital role of the lighthouse in protecting vessels navigating these challenging waters.

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many isolated maritime outposts, Double Island Point Lighthouse has accumulated a rich folklore of unexplained phenomena and mysterious occurrences over its long history. The combination of its dramatic location, the often extreme weather conditions, and the isolation experienced by lighthouse families has contributed to a compelling collection of mysteries that continue to intrigue visitors and researchers alike.

The Phantom Keeper: The most well-documented mystery centers around what keepers’ families came to call “The Phantom Keeper.” Multiple lighthouse families, spanning several decades, reported similar experiences of hearing footsteps climbing the tower stairs late at night, particularly during storms. The footsteps followed the exact pattern that keepers would use during their watch changes, including the distinctive pause at the halfway landing where they would typically catch their breath.

This phenomenon was first recorded in William Simpson’s logbooks (1898-1916), where he made careful notes about the sounds, attempting to find rational explanations. The mystery deepened when later keepers reported that these footsteps were often accompanied by the distinct smell of kerosene, even years after the lighthouse had converted to electric power. Keeper McKay (1956-1973) maintained a separate journal of these occurrences, noting that they seemed to intensify during particularly severe weather.

The Signal Light Mystery: Another persistent mystery involves unexplained lights seen from the lighthouse, particularly during the winter months. These lights, described as having a distinctive blue-green color, have been reported moving across the water in patterns that defy normal maritime navigation. Kabi Kabi elders suggest these lights correspond to traditional stories about spirit guides that protect travelers in the area.

The Weather Phenomenon: The lighthouse site experiences unusual meteorological phenomena that have never been fully explained. The area is known for its “ghost storms” – electrical storms that appear to concentrate around the point but produce no rain. These events, well-documented in weather records, are often accompanied by unusual electromagnetic disturbances that affect equipment in the lighthouse.

Keeper Thompson reported several instances in the 1980s where these storms coincided with all electrical equipment in the lighthouse failing simultaneously, only to restart without explanation when the atmospheric conditions returned to normal. Modern scientific investigations suggest these phenomena might be related to unique geological features beneath the point, though no definitive explanation has been found.

The Children’s Stories: Some of the most intriguing accounts come from the children who grew up at the lighthouse. Multiple keepers’ children, across different decades, reported similar experiences of hearing children’s laughter in the empty areas around the keeper’s cottages, particularly near the old schoolroom. The Stephenson children (1927-1942) kept a diary that included detailed descriptions of their encounters with what they called “the other lighthouse children.”

Wartime Mysteries: The World War II period added its own layer of unexplained events. Keeper Weber’s logs contain carefully worded references to unusual occurrences that were never officially explained, even after the declassification of military records. These included reports of lights seen beneath the water’s surface and unexplained radio signals received during periods of heavy atmospheric disturbance.

Modern Phenomena: Even after automation in 1992, Double Island Point continues to generate mysterious tales. Maintenance workers report unexplained equipment behavior, particularly during the anniversary of significant historical events at the lighthouse. The most recent documented incident occurred in 2018, when automated monitoring systems recorded powerful electromagnetic disturbances that coincided with reports of unusual light phenomena from passing vessels.

Indigenous Perspective: Kabi Kabi traditional owners offer a unique perspective on these mysteries. Their cultural knowledge suggests that many of these phenomena are natural manifestations of the headland’s role as a boundary place between physical and spiritual realms. Their traditional stories speak of Double Island Point as a place where the veil between worlds becomes thin during certain astronomical and seasonal alignments.

Scientific Investigation: Recent scientific studies have attempted to explain some of these phenomena through the investigation of geological, atmospheric, and electromagnetic conditions unique to the headland. While some incidents have found rational explanations through these investigations, others remain mysteriously resistant to scientific analysis. The lighthouse continues to be a site of interest for researchers studying unusual maritime and atmospheric phenomena.

Current Status:

Today, Double Island Point Lighthouse continues its vital role in maritime safety while standing as a significant heritage site. The lighthouse was automated in 1992, and is now operated by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). The site has been carefully preserved, maintaining much of its original character and equipment.

The lighthouse precinct is managed as part of the Great Sandy National Park, with regular maintenance ensuring both its operational reliability and historical authenticity. While access is limited due to the sensitive nature of the equipment and its heritage status, the lighthouse remains an iconic landmark and crucial navigation aid on the Queensland coast.