Although relatively small in stature the Cape Inscription lighthouse is located at a place with a very big history. Dating back to when modern Australia separated from Gondwana, almost before time began, and became our continents western extremity, to the 25th October, 1616 when Dirk Hartog became the first European to set foot on our shores and to the darkest day of WWII on 19th November, 1940 when the HMAS Sydney II was lost with all hands due west of this place. Cape Inscription has witnessed more than its fair share of epoch defining events.

Standing at the western extremity of our continent Cape Inscription Lighthouse is also one of Australia’s most historically significant maritime locations as it’s the site where Dutch explorer Dirk Hartog made the first recorded European landing on Australia in 1616, which fundamentally altered the prevailing knowledge of the southern hemisphere redrew the maps of the World!

Cape Inscription Lighthouse rises from the limestone cliffs at the northern tip of Dirk Hartog Island, 209 kilometres from Shark Bay’s township of Denham and guards the entrance to the Naturaliste Channel and the approaches to Shark Bay. This remote light has served mariners navigating the crucial shipping routes between Fremantle and Singapore for over a century, standing watch over waters that bore witness to centuries of European exploration before the station’s establishment.

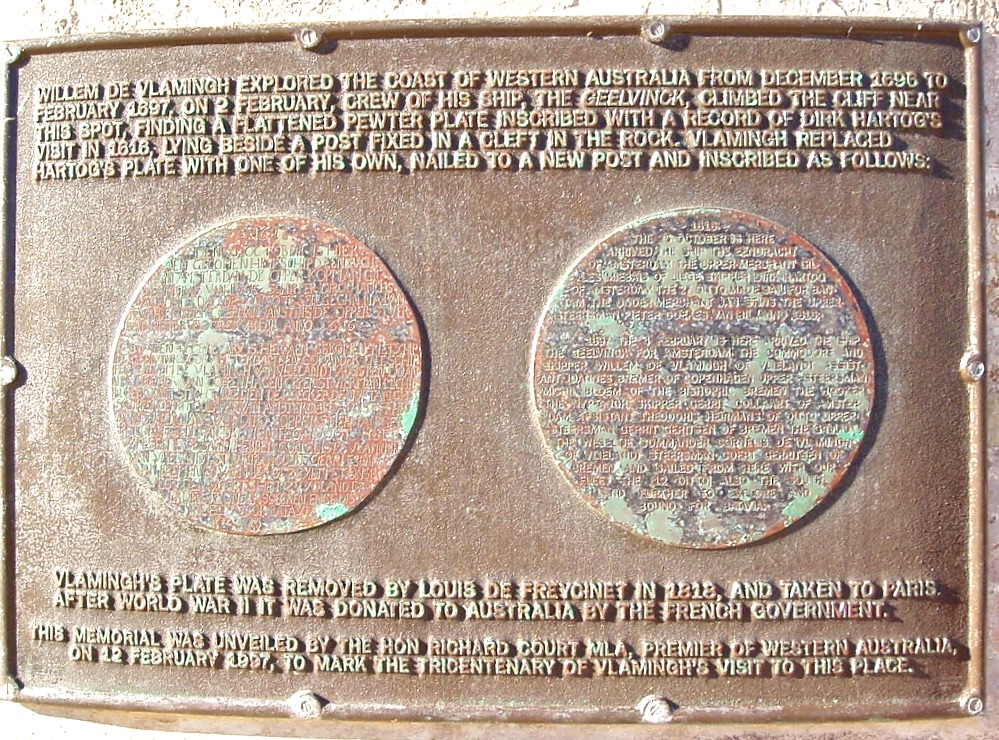

The cape gained its name from the inscribed pewter plates left by successive explorers, Dirk Hartog in 1616, Willem de Vlamingh in 1697 and various other navigators who have documented their passages through these waters. Today, this spectacular location sits on the traditional lands of the Malgana people, who know the island as Wirruwana which now forms part of the Shark Bay World Heritage Area recognised internationally for its unique flora and fauna.

By the early twentieth century the Western Australian government recognised the critical need to improve navigation to the entrance to Shark Bay which served as the gateway to remote settlements, pearling operations, and pastoral stations of the greater Gascoyne region. The growth of maritime traffic using the faster southern route to Singapore demanded improved navigational safety through the complex approaches of channels, reefs, and powerful tidal currents.

Cape Inscription lighthouse was commissioned on 1 March 1910, becoming the second of six new lights built by the Government of Western Australia in the period 1908 to 1915 along the Western Australian coast to fill in navigation black spots identified by shipping companies using the route to Singapore. At this time lighthouse construction and maintenance remained the responsibility of the state government though control would later transfer to the Commonwealth on 1 July 1915.

The construction of the lighthouse and its supporting infrastructure at this remote and inhospitable location stands as a remarkable engineering achievement. Work began in October 1908, with preliminary surveys conducted in 1907 during which the historic posts left by Vlamingh and Hamelin were carefully removed to Perth for preservation and replaced with new timber posts bearing commemorative plaques. The jetty was built first, a substantial structure some 71m long extending into Turtle Bay followed by the construction of an inclined tramway completed in 1909 to transport materials and supplies from the landing point to the lighthouse site atop the cliffs.

The lighthouse tower represents a distinctive departure from Western Australia’s other early twentieth century lights. While Cape Leveque employed prefabricated cast iron and many coastal stations utilised local stone, Cape Inscription’s 15m tower was constructed entirely of non-reinforced concrete, a testament to the resourcefulness of early twentieth century engineers who accomplished this feat by carting materials and water to the site in hogsheads, with horses pulling small trolleys along the tramway. The contractors for the project were the Public Works Department, overseen by engineer Mr. K. Farrar. An underground tank of 20,000 gallons capacity with a concrete catchment area was also constructed near the cliff edge to provide vital water storage for the isolated station.

The elegant concrete tower was fitted with optical equipment transferred from Breaksea Island lighthouse, a Wilkins & Co. lantern housing a third-order Barbier, Benard & Turenne Fresnel lens that had previously served at the earlier lighthouse at the entrance to King George Sound. This sophisticated French optical apparatus was mounted on a precision pedestal with a clockwork mechanism that rotated a revolving screen to produce the lighthouse’s distinctive original characteristic of an occulting light: 5 seconds of light followed by 2.5 seconds of darkness (Oc.W. 5s eclipse 2.5s), achieved by the clockwork driven revolving screen that rotated around the light source.

Comprehensive support facilities were constructed to sustain operations at this isolated posting. Two keepers and their families were stationed at Cape Inscription living in fortress-like quarters constructed using thick concrete blocks to withstand the frequent savage weather and provide some respite from the extreme temperature variations experienced at this windswept location. Additional structures included a storehouse, stables for the horses that powered the tramway operations, an oil store, and a privy, all essential infrastructure for maintaining self-sufficiency in this remote location far removed from support services.

Life at Cape Inscription demanded exceptional resilience from the keepers and their families. The station’s isolation was profound, supplies arrived by sea via the jetty at Turtle Bay, then had to be hauled up the tramway to the lighthouse precinct. Fresh water, a precious commodity on this limestone island, was initially drawn from Sammy Well and carted on horse-drawn wagons to make concrete for the tower’s construction, though the completed lighthouse’s large catchment system later provided more reliable fresh water supplies. The keepers maintained operations despite the extreme remoteness, their dedication exemplified by the service of lightkeepers like William Edward Chessher, who served from the station’s commissioning until July 1917.

Among the assistant lightkeepers who served at Cape Inscription was Patrick Thomas George Baird, son of Patrick David Baird who kept lights at Rottnest and Cape Naturaliste. Young Patrick served from 15 February 1915 until early 1916 when he left for military service. Tragically, he was killed in action at Fleurbaix, France on 3 November 1916, aged just 21, his first posting in the lighthouse service cut short by the carnage of the First World War, a poignant reminder that even Australia’s most remote outposts contributed to the global conflict.

The march of technology reached Cape Inscription remarkably early. On 15 May 1917 after only seven years of manned operation the lighthouse was converted to automatic acetylene operation and demanned making it one of the earliest automated lighthouses in Australia. This conversion necessitated changing the characteristic to three flashes every 15 seconds (Fl.(3)W. 15s).

The supporting infrastructure faced its own challenges. In 1937 a severe storm destroyed the jetty at Turtle Bay, though the tramway remained in place and visible through the mid-1950s. Despite these difficulties, the lighthouse continued its automated operation requiring only periodic maintenance visits.

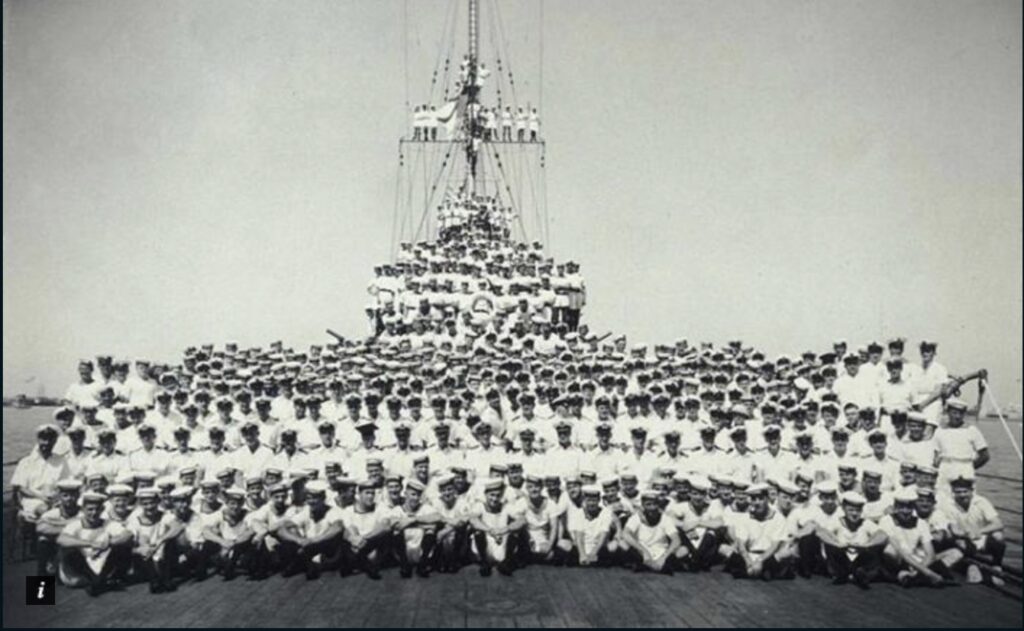

On 19 November 1941 the waters off Cape Inscription witnessed Australia’s greatest naval tragedy during the Second World War when the light cruiser HMAS Sydney encountered what appeared to be a Dutch merchant vessel approximately 106 nm west of the lighthouse. The vessel was actually the German auxiliary cruiser HSK Kormoran, and as the Sydney approached to verify the ship’s identity the Kormoran opened fire at close range crippling the Australian cruiser in minutes. Both vessels were destroyed in the half-hour engagement that followed. While 318 of Kormoran’s 399 crew survived and were rescued all 645 personnel aboard Sydney were lost making it Australia’s worst naval disaster and the largest Allied warship lost with all hands during the war. The German commander had been investigating Shark Bay at the time intending to lay mines along the shipping routes that Cape Inscription had overseen for three decades. For 12 days the government maintained strict secrecy about Sydney’s loss and the wreck’s location remained unknown for 67 years until both vessels were discovered in March 2008. The tragedy cast a long shadow over the region, with the lighthouse continuing its silent vigil over waters that had claimed so many young Australian lives. Ironically, memorials to those lost on both the HMAS Sydney and the Kormoran stand side by side on the Carnarvon foreshore.

The character and operation of the light remained unchanged for decades until conversion to solar power in the 1980s, representing Australia’s growing embrace of renewable energy for its remote lighthouse network. By 1987, the light was solar powered and a helicopter pad had been constructed to allow modern maintenance access to this isolated station.

In 2012, recognizing the historical significance of the site the Shire of Shark Bay undertook restoration of the lighthouse keepers’ quarters, which had fallen into disrepair during the decades since automation. These restored quarters now provide interpretation of the station’s history and stand as tangible links to the era of manned lighthouse operations on this historic island.

The lighthouse’s heritage significance has been formally recognized through multiple designations. The lighthouse and quarters were listed on the Register of the National Estate in March 1978 and on the Heritage Council of Western Australia’s Register of Heritage Places in August 2001, acknowledging their historical, technical, and cultural importance. The broader Cape Inscription area, encompassing the landing site and historic posts, was included in the Australian National Heritage List, recognizing its profound significance to Australia’s maritime history and European exploration.

Today, Cape Inscription Lighthouse continues its vital navigational role under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, its concrete tower rising 15 metres above sea level and visible to mariners traversing the approaches to Shark Bay. The solar-powered beacon flashes its automated signal across waters rich with marine life—humpback whales migrate past these shores, sea turtles nest on the beaches, and the unique marine ecosystems of the Shark Bay World Heritage Area flourish beneath the lighthouse’s watchful beam.

The island itself has undergone a remarkable transformation. Dirk Hartog Island National Park, created in November 2009, now encompasses almost the entire 63,000-hectare island. The groundbreaking “Return to 1616” ecological restoration project has successfully eradicated introduced sheep, goats, and feral cats, paving the way for the reintroduction of native mammals that disappeared during the island’s pastoral era. This ambitious conservation effort aims to restore the island’s ecology to approximate the pristine conditions that Dirk Hartog himself observed in 1616—a fitting tribute at a site where European awareness of Australia’s west coast began.

The lighthouse and island are now jointly managed by the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions and the Malgana Aboriginal Corporation, ensuring that traditional custodianship and contemporary conservation practices work in harmony. The restored keepers’ quarters feature interpretive panels detailing the site’s layered history—from ancient Malgana occupation through successive European explorations to the lighthouse era and modern conservation achievements.

Cape Inscription is still very isolated and difficult to get to and the best way is by specialist 4X4 tours, boat from Denham or, if you can afford it, helicopter.

Technical Specifications

First Exhibited: 1 March 1910

Status: Active (Automated 15 May 1917)

Location: Cape Inscription, northern tip of Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia Construction: 1908-1910

Construction Material: Non-reinforced concrete tower

Contractor: Public Works Department, overseen by engineer Mr. Farrar

Tower Height: 15m

Original Light Source: Oil-fired (kerosene)

Original Lens: Barbier, Benard & Turenne third-order Fresnel lens

Original Lantern: Wilkins & Co.

Original Characteristic: Occulting white—light 5 seconds, dark 2.5 seconds (Oc.W. 5s eclipse 2.5s), achieved by clockwork driven revolving screen

1917 Conversion: Automatic acetylene operation with AGA lantern

1917 Light Characteristic: Group flashing—3 white flashes every 15 seconds (Fl.(3)W. 15s)

1980s Conversion: Solar power

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA)

Land Management: Dirk Hartog Island National Park, jointly managed by Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions and Malgana Aboriginal Corporation

Coordinates: 21° 48′ S, 114° 06′ E