It’s easy to get lulled into a false sense of security when observing the relatively enclosed waters surrounding the Yorke Peninsula, with the Gulf of St. Vincent to the east and Spencer Gulf to the west—it’s hard to imagine that these waters could have claimed the toll of ships and lives that they have. But what makes these waters so treacherous is not necessarily giant swells and powerful currents but is more to do with gale force winds and shallow reef-infested waters that can turn from a mill pond into a raging tempest within minutes.

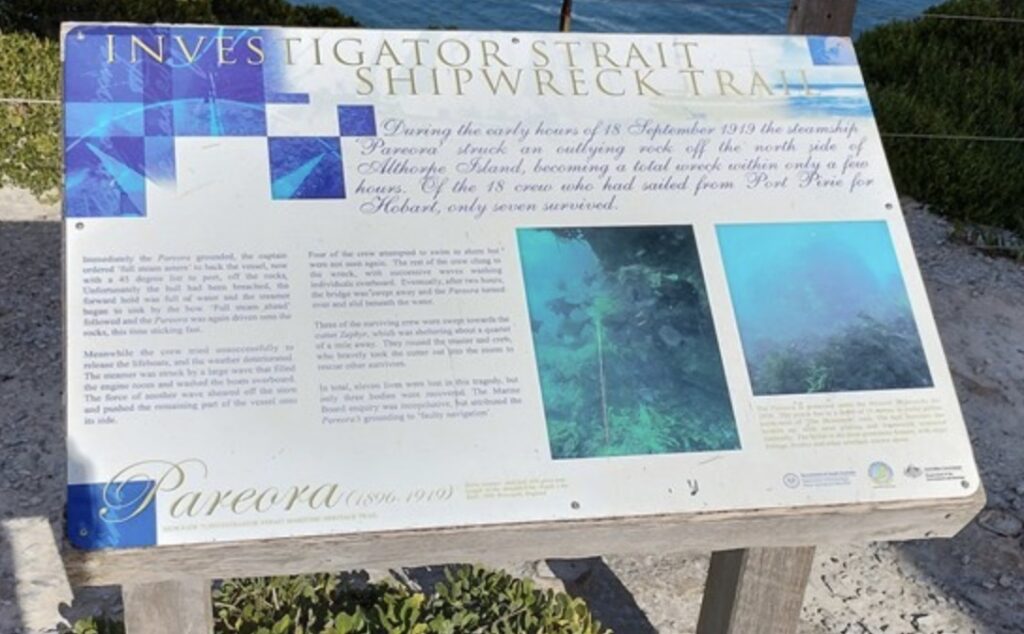

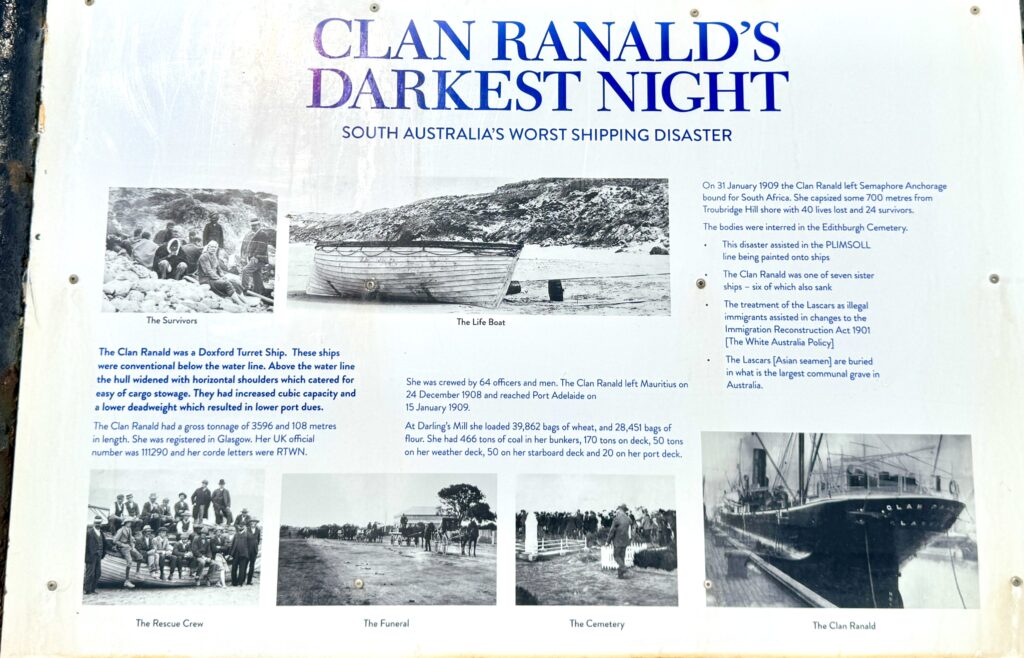

Looking at it today, it’s hard to imagine why these waters proved so catastrophic with over eighty-five shipwrecks that transformed these waters into one of Australia’s most notorious maritime graveyards. The peninsula’s strategic position between the Southern Ocean and Spencer Gulf created shipping lanes essential for the colony’s development, particularly for vessels carrying copper from the booming mines at Wallaroo and Moonta, yet these same waters demanded a deadly toll from mariners attempting to navigate the infamous Troubridge Shoals and hidden reefs.

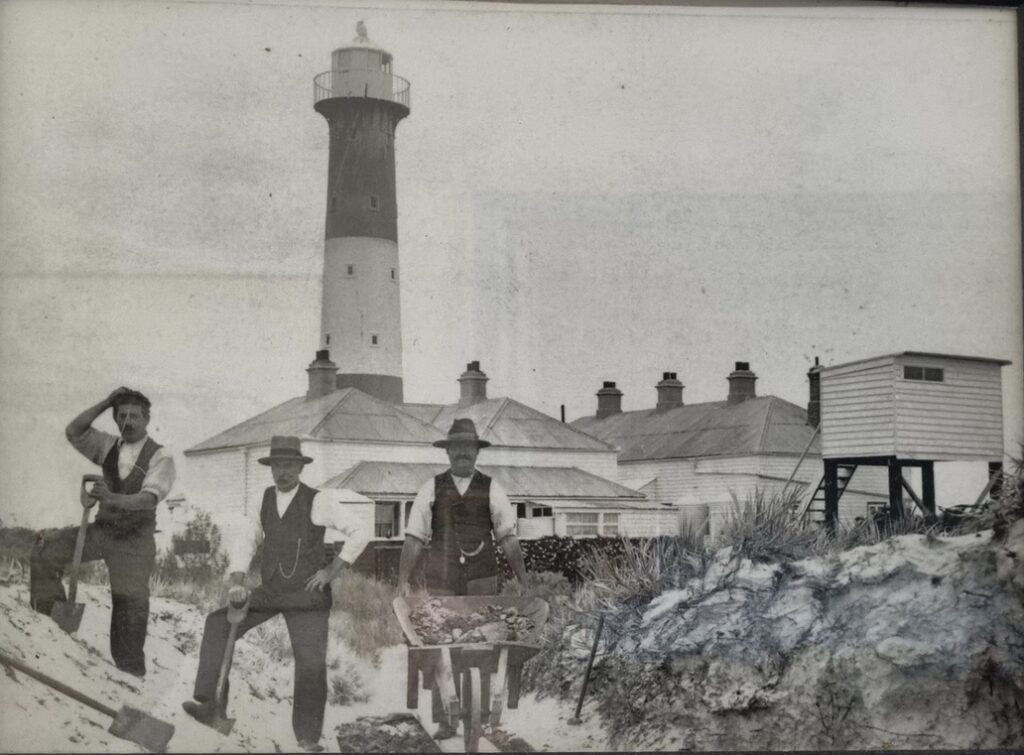

The colonial authorities’ response was decisive: a comprehensive network of lighthouses would guard these deadly approaches, each lighthouse destined to develop its own character shaped by isolation, technological innovation, and the weight of lives that depended on their unwavering vigilance. The first and most dramatic guardian arose from the very reef system that claimed so many vessels. Troubridge Island Lighthouse, established in 1856 on the dangerous shoals themselves, represented an audacious solution to an intractable problem. Built of stone masonry and painted stone colour, this 24.7-metre tower created one of South Australia’s most isolated yet critical navigation aids, with keeper families living in complete separation from civilization.

The isolation on Troubridge Island was absolute, fostering remarkable resilience among the lighthouse families who called this remote outcrop home for 125 years until automation in 1981. Perhaps no story better captures the human spirit here than that of Czech-born surrealist artist Voitre Marek, who served as lighthouse keeper during the 1960s and 1970s, transforming the island’s isolation from burden into artistic inspiration while raising his young family surrounded by endless water and the constant reminder of maritime disaster.

As shipping traffic to the northern ports increased with the copper boom, Corny Point Lighthouse was completed in 1882 at the peninsula’s northernmost extremity. It was specifically designed to protect grain ships and copper vessels approaching Port Victoria, Moonta Bay and Wallaroo. Unlike Troubridge Island’s complete isolation, Corny Point’s mainland location allowed for somewhat easier supply runs, though the station remained notably remote and demanding for keeper families.

Seven kilometres offshore from the peninsula’s tip, Althorpe Island Lighthouse earned its romantic moniker when first lit on Valentine’s Day, 14 February 1879. Construction had begun in 1877 but was tragically delayed when an accident claimed the foreman’s life in 1878. Built of solid limestone and standing 20 metres tall, 91 metres above sea level, this lighthouse maintained 112 years of continuous human presence until it was automated in 1991, representing perhaps the most psychologically challenging posting due to its complete isolation and constant awareness of shipwrecks in the waters below.

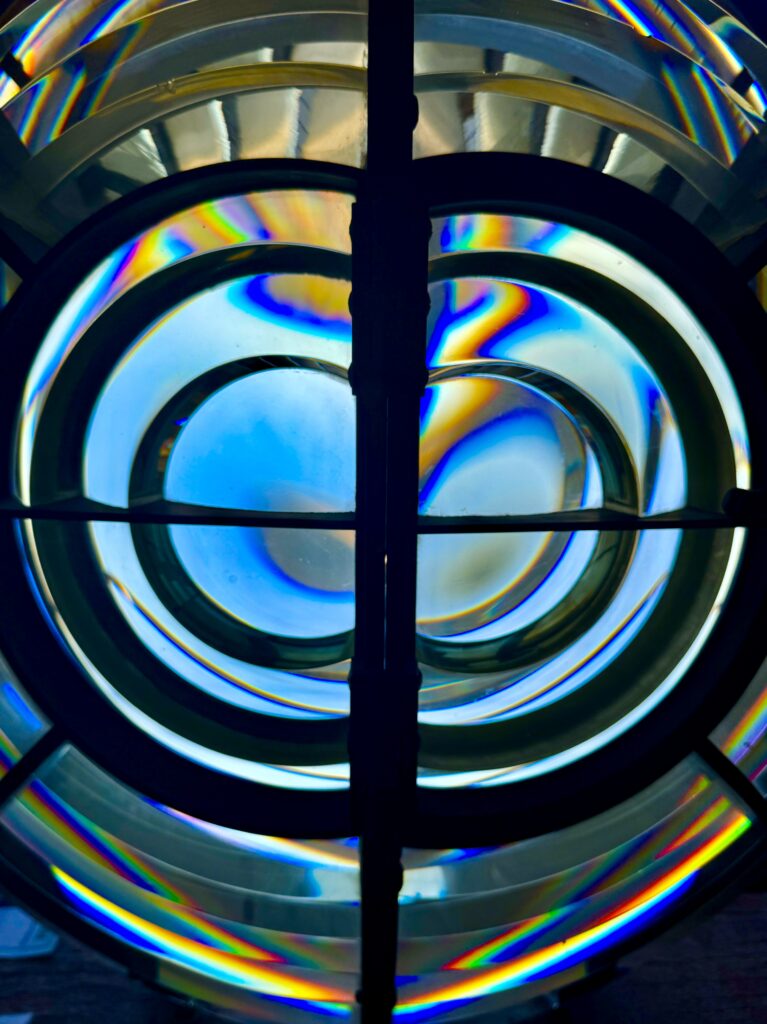

The mid-20th century brought technological revolution to lighthouse operations. Cape Spencer Lighthouse, commissioned as an automatic beacon in 1950 with a major concrete upgrade in 1970, represented a new era requiring no resident keepers yet providing crucial 23-nautical-mile guidance to vessels navigating the peninsula’s southern approaches. West Cape Lighthouse, constructed of stainless steel in 1980, completed this evolution as the peninsula’s newest and most technologically advanced sentinel, entirely automated from day one.

Troubridge Hill Lighthouse was built in 1980 to complement its namesake island lighthouse. It was a revolutionary design for its time being constructed of earthquake-resistant clay brickwork with every brick designed to fit into the graceful tapered conical shape of the tower. This beautiful 30-metre brick tower provided additional mainland navigation reference, creating a sophisticated network where multiple beacons worked in concert. This integrated system marked advanced understanding of navigational science with overlapping coverage ensuring vessels approaching from any direction had multiple reference points for unprecedented positional accuracy.

The transition from manned to automated operations marked more than technological advancement—it ended a unique way of life where lighthouse families created isolated communities bound by shared purpose. These families developed extraordinary self-sufficiency, serving as doctors, teachers, mechanics, and weather observers while maintaining their vigilant watch through storms and equipment failures, knowing their dedication was the thin line between safe passage and catastrophe for countless vessels.

Today, these six lighthouses continue their watch over waters that claimed so many vessels in the age of sail and steam. Though GPS and modern navigation have reduced their critical importance, their beams still sweep across dangerous waters each night, serving not just as navigation aids but as a reminder of the past when these waters claimed so many unwary ships and their crews.

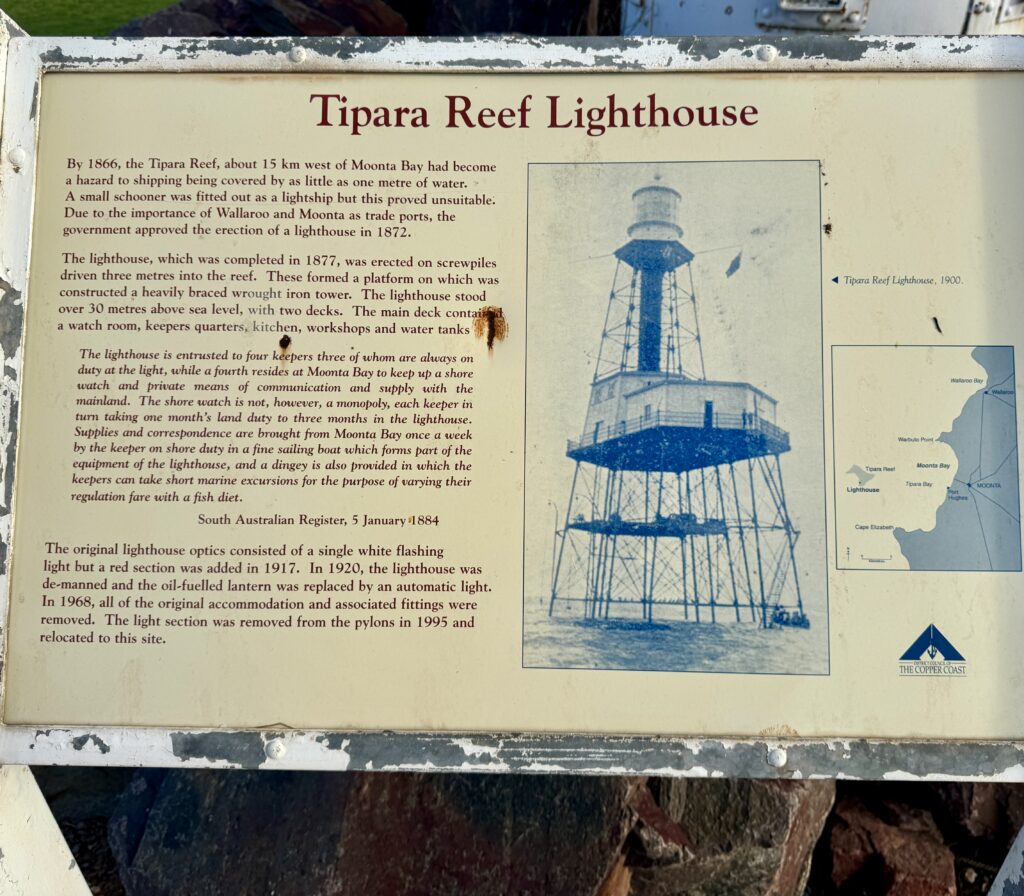

Footnote: As I mentioned in my Wallaroo section I happened by chance to discover a lighthouse I didn’t know existed in the main street of this town. The Tapia Reef lighthouse use to be located 15km west of Moonta Bay to alert ships of a a dangerous reef was first lit in 1877 but decommissioned in 1968 and finally demolished with the tower being affored pride of place in Wallaroo in 1995.

Technical Specifications

Troubridge Island Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1856 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Troubridge Island, off eastern Yorke Peninsula

Tower Height: 24.7 metres | Focal Elevation: 25 metres above sea level

Construction: Stone masonry painted stone colour

Range: Eastern Spencer Gulf approaches

Notable: Manned 1856-1981; home to artist Voitre Marek; now conservation park

Corny Point Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1882 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Northernmost extremity of Yorke Peninsula

Tower Height: 30 metres

Construction: Clay brick

Range: Northern Spencer Gulf approaches

Notable: Earthquake-resistant design; guided copper and grain ships; Horizontal Pine nearby

Troubridge Hill Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1980 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Troubridge Hill, Yorke Peninsula

Tower Height: 30 metres

Construction: Earthquake-resistant clay brickwork

Range: Mainland navigation reference

Notable: Special award from SA Clay Brick Association; complements island lighthouse

Althorpe Island Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 14 February 1879 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Althorpe Island, 7km offshore

Tower Height: 20 metres | Focal Elevation: 91 metres above sea level

Construction: Solid limestone masonry

Range: 24 nautical miles

Notable: Valentine’s Day commissioning; manned 1879-1991

Cape Spencer Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1950 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Cape Spencer, Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park

Focal Elevation: 78 metres above sea level

Construction: Cement structure (1970 upgrade)

Range: 23 nautical miles

Light: 120v 1000w Tungsten Halogen

Notable: Automatic from inception

West Cape Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1980 | Status: Active (Automated)

Location: West Cape, Yorke Peninsula

Construction: Stainless steel

Notable: Most modern lighthouse on peninsula; completes Spencer Gulf navigation network

Disclaimer: Due to the need to get across the “Top End” in the dry season (which usually ends in October), and to spend time in the outback on the way north I have rushed the first stage of Act 3. In order to document the lighthouses I’ve visited I’ve enlisted the help of Elon Grok and A.I. Claude to help on these Lighthouse Stories. Despite their claims of infallibility I’ve found some of their facts not to be accurate and would welcome any corrections, which they will learn from! I have also sourced a few photos from the public domain (i.e. Dr Google) to compliment the shots I’ve taken on my travels. I would like to concentrate on telling my personal experiences and thoughts as I travel around and intend to reedit these lighthouse stories when I have time.