Kangaroo Island occupies a unique place in Australia’s maritime history, for it was often the first landfall ships would make after leaving Cape Town on their voyage from England to the colonies of New South Wales. Upon this landfall, captains faced a critical decision that could mean the difference between safe passage and disaster, whether to take the starboard southerly route around the island’s treacherous southern coast, or head to port and navigate the Investigator Strait—the infamous Back Stairs Passage, first charted by Matthew Flinders in 1803.

Both routes came with considerable risk as evidenced by over eighty shipwrecks scattered around the island according to some accounts.

As this gruesome toll mounted colonial authorities realised they needed to improve safety. Their response was to commission a series of lighthouses to improve safety, monitor ship movements and act as first responders if a ship got into difficulties.

Each lighthouse would develop its own personality, shaped by tragedy, isolation, and the strange occurrences that seem to follow those who stand watch over dangerous waters.

The first of these lighthouses was initially christened the Sturt Light after explorer Charles Sturt, and was to be built at Cape Willoughby on the island’s south-eastern tip to encourage mariners to take the more southerly route and avoid the notorious Back Stairs Passage, as the waters between Kangaroo Island and the mainland had already earned a fearsome reputation.

However the original name didn’t stick and on 10th January, 1852 the Cape Willoughby lighthouse was lit for the first time, making it South Australia’s very first lighthouse.

Unfortunately the advent of this lighthouse didn’t end the carnage and over the years its keepers witnessed numerous maritime disasters including the iron barque You Yangs in 1890. Ironically G. E. Luckett, who would later become the second keeper at Cape du Couedic, was a passenger of this ship when it was wrecked at Cape Willoughby, a stark reminder that even those dedicated to maritime safety were not immune to the sea’s dangers.

The isolation at Cape Willoughby proved as challenging as the treacherous waters. The lighthouse keepers lived in splendid solitude and the psychological strain of such isolation has led to persistent rumours of unexplained phenomena including the mysterious deaths of a number of those on station, most notably the sudden death of the head keeper Donald McCleod in 1878, whose ghost is said to still stand watch in the tower.

Six years after Cape Willoughby’s inauguration, authorities turned their attention to the island’s northwestern approach, after the barque Loch Sloy was wrecked in Maupertius Bay while attempting to navigate the Back Stairs Passage en route to Adelaide.

In 1858, they constructed something entirely unique, Cape Borda Lighthouse, Australia’s only square lighthouse and South Australia’s highest standing atop the sheer cliffs on the islands north coast.

But Cape Borda was destined to be more than just architecturally distinctive as the lighthouse keepers here lived with an additional responsibility that bordered on the theatrical, they operated a signal cannon originally installed to warn of invading Russian ships but later used as both warning and comfort to mariners navigating the perilous strait below.

The isolation at Cape Borda was so complete that the station has its own small cemetery where the weathered headstones tell poignant stories of families who chose duty over comfort. These graves face the endless ocean, final testament to people who spent their lives ensuring others could safely cross waters that had claimed so many. The cemetery holds the remains of children who never knew life beyond this lonely outpost, of wives who died far from their families and keepers who literally worked themselves into early graves.

This isolation and the adjacent maritime disasters seem to have left an indelible mark, with some visitors reporting an overwhelming sense of melancholy that descends without warning, particularly during twilight hours when the lighthouse beam begins its nightly vigil.

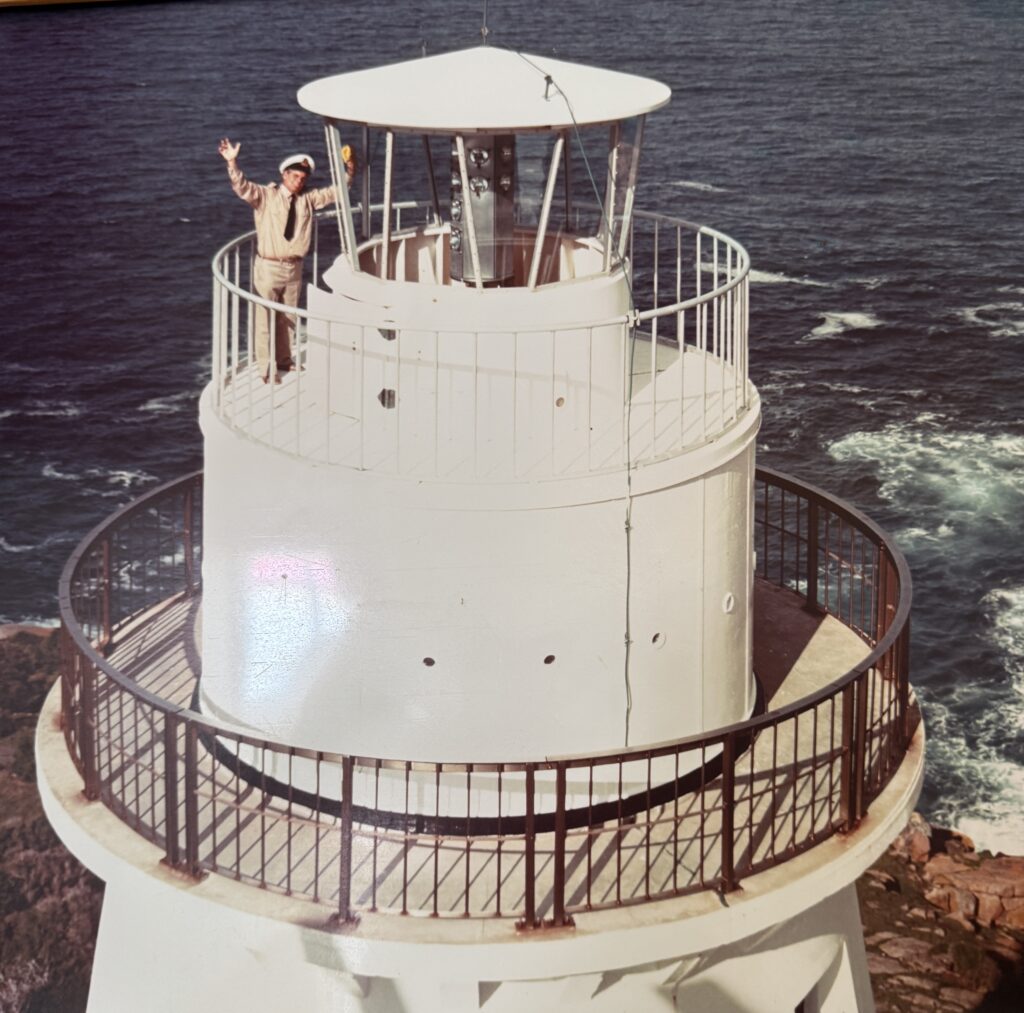

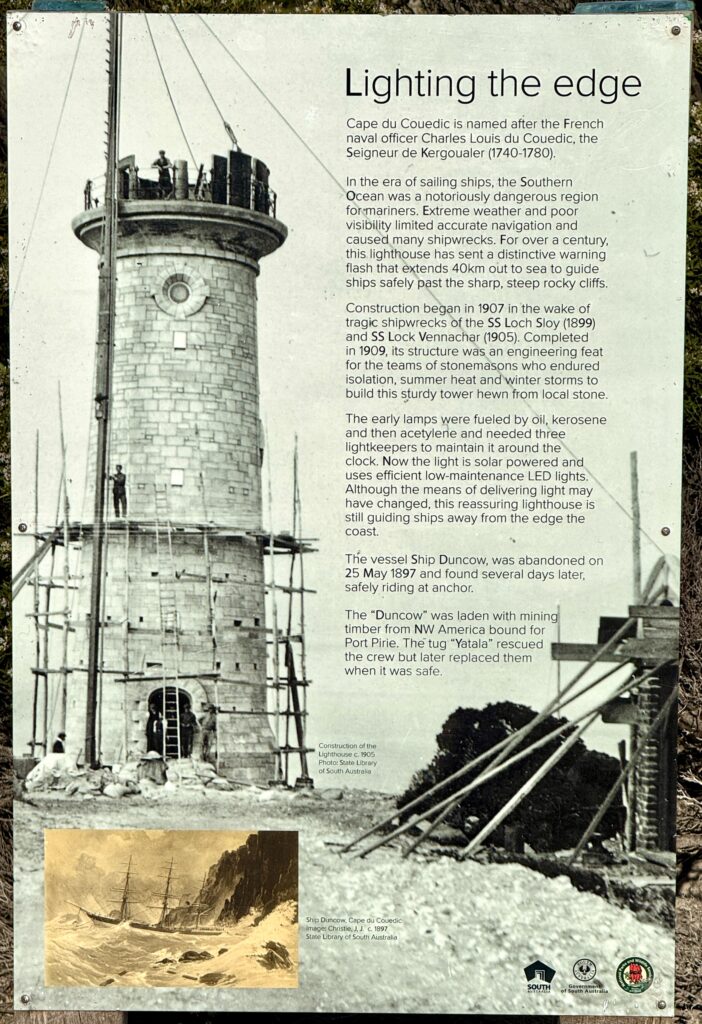

Despite the operation of these two lighthouses the toll continued to mount with three ships wrecked and 79 lives lost at the western end of the island. In 1902 the South Australian Marine Board recommended the construction of a lighthouse at Cape du Couedic, at the island’s southwestern extremity. Commissioned in 1906, construction began on what would become a 25m granite tower to watch over Kangaroo Island’s most perilous approaches, though the project would not be completed until 1909.

Standing within what would become Flinders Chase National Park, Cape du Couedic developed its own distinctive personality, two precise flashes every ten seconds and topped with a striking red crown. But this lighthouse was born from tragedy and seemed destined to witness more.

The sinking of the Portland Maru was one of the biggest shipwrecks off the coast of Kangaroo Island. Carrying wheat from Port Lincoln to Japan the 5865 ton freighter ran aground and sank on March 19th, 1935 and is now a popular, if shark infested, scuba diving destination.

In several instances the keepers at Cape du Couedic could see the wrecks of ships they had been unable to save in the waters below their tower. The psychological weight of watching vessels founder despite their warning light created a unique form of trauma among the lighthouse staff. Some keepers reported experiencing what they described as “phantom ships”, vessels they would see struggling in the waters that, upon investigation, proved to be optical illusions created by their imagination of the interplay of moonlight on water.

The final chapter in the lighthouses of Kangaroo Island represents both technological advancement and the beginning of an end. Cape St Albans Lighthouse, constructed in 1907—a year after Cape du Couedic was commissioned though still two years before its completion—was revolutionary, South Australia’s first purpose-built unattended automatic lighthouse.

While its three elder siblings required dedicated keepers and their families to maintain round-the-clock vigilance, Cape St Albans was designed to operate without human intervention. Standing on the island’s eastern promontory, this automated beacon represented the beginning of the end for the era of lighthouse keepers. No longer would families need to endure the splendid isolation, the psychological pressures, and the constant confrontation with maritime tragedy that defined life at manned stations.

Yet even automation could not completely eliminate the human element. The lighthouse still required occasional maintenance visits, and these brief encounters with the automated beacon produced their own strange stories. Workers reported that the mechanised light seemed to develop its own rhythms and quirks, as if the absence of human presence had allowed something else to inhabit the tower. Tools would be found moved from where they were left, and the automatic timing mechanisms would occasionally falter in ways that suggested more than mere mechanical failure.

In keeping with its unmanned status Cape St Albans is on private land and not accessible to the public.

Today, these four guardians continue their eternal watch, though GPS satellites have largely replaced their critical navigation role. They’ve become storytellers instead, each tower holding memories of storms weathered, ships guided safely home, lives lost despite their vigilant warnings, and generations of keepers who chose isolation and duty over the comfort of mainland life.

The shipwrecks that prompted their construction remain scattered around Kangaroo Island’s waters in various states of decay, from the massive Portland Maru to smaller coastal traders that simply vanished into the Southern Ocean.

Each wreck is a reminder of the power and unpredictability of the ocean and of the thin line between safe passage and disaster.

The lighthouses stand as monuments not just to maritime safety, but to human resilience in the face of isolation, tragedy, and the constant reminder of mortality that surrounds those who live and work near dangerous waters. Their beams still sweep across the darkness each night, perhaps now more for the comfort of the living than the guidance of ships, continuing to cast their protective light over one of Australia’s most treacherous and beautiful coastlines.

Together, they remind us that some of history’s most important work happened in the loneliest places, conducted by people whose names we’ve mostly forgotten but whose dedication continues to inspire us, and whose spirits, some say, may never have truly left their posts.

Technical Specifications – Cape Willoughby Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1852

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Eastern extremity of Kangaroo Island, South Australia

Construction: 1852, granite and limestone quarried from cliff base

Tower Height: 27 metres

Steps to Summit: 102

Focal Elevation: Approximately 75 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Local granite and limestone masonry

Original Name: Sturt Light (after Captain Charles Sturt)

Current Light: LED beacon technology

Range: Covers Backstairs Passage approaches

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: South Australia’s oldest lighthouse

Notable Features: First lighthouse built in South Australia; materials quarried on-site from cliff; originally housed three keeper families; 1.9km heritage trail; panoramic views across Backstairs Passage; located within Cape Willoughby Conservation Park

Technical Specifications:

Cape Willoughby Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1852

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Eastern extremity of Kangaroo Island, South Australia

Construction: 1852, granite and limestone quarried from cliff base

Tower Height: 27 metres

Steps to Summit: 102

Focal Elevation: Approximately 75 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Local granite and limestone masonry

Original Name: Sturt Light (after Captain Charles Sturt)

Current Light: LED beacon technology

Range: Covers Backstairs Passage approaches

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: South Australia’s oldest lighthouse

Notable Features: First lighthouse built in South Australia; materials quarried on-site from cliff; originally housed three keeper families; 1.9km heritage trail; panoramic views across Backstairs Passage; located within Cape Willoughby Conservation Park

Cape Borda Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1858

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Northwestern extremity of Kangaroo Island, South Australia

Construction: 1858, local stone masonry

Tower Height: 9 metres (30 feet)

Focal Elevation: 155 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Square stone tower construction

Light Characteristic: Group of four white flashes every 20 seconds

Current Light: Automated beacon technology

Range: Covers Investigator Strait approaches

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: Australia’s only square stone lighthouse

Notable Features: Unique square stone tower design; highest focal elevation in South Australia; historic signal cannon; keeper’s cemetery on site; originally supplied via Harvey’s Return jetty with rail system; located within Flinders Chase National Park; guided ships through the notorious “Roaring Forties” trade winds

Cape du Couedic Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1909

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Southwestern extremity of Kangaroo Island, South Australia

Construction: 1906-1909, local granite quarried on-site

Tower Height: 25 metres (82 feet)

Focal Elevation: 103 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Local granite masonry with reinforced concrete stairs and floors

Light Characteristic: Two white flashes every ten seconds

Original Lens: Third Order Fresnel lens by Chance Brothers

Current Light: LED beacon with six-position lamp changer

Range: Covers southwestern approaches to Kangaroo Island

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: Listed on State and National Heritage Registers

Notable Features: Distinctive red crown; built with innovative reinforced concrete internal structure; materials hauled up 85m cliff via flying fox from Weirs Cove jetty; three keeper cottages (Troubridge, Karatta, and Parndana); located within Flinders Chase National Park; tower not open to public but grounds accessible year-round

Cape St Albans Lighthouse

First Exhibited: 1908

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Eastern promontory, Dudley Peninsula, Kangaroo Island

Construction: 1907, purpose-built automatic design

Construction Material: Stone masonry construction

Focal Elevation: Approximately 60 metres above sea level

Light Characteristic: Automated beacon (original acetylene system)

Current Light: Modern automated beacon technology

Range: Covers Backstairs Passage eastern approaches

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: South Australia’s first purpose-built unattended lighthouse

Notable Features: Revolutionary unmanned design; part of transition from state to Commonwealth Lighthouse Service; located on private land – not accessible to public; positioned between Cape Willoughby (south) and Antechamber Bay; first of nine automatic lights built during SA transition period; guided vessels through Backstairs Passage for 150+ years.

Disclaimer: Due to the need to get across the “Top End” in the dry season (which usually ends in October), and to spend time in the outback on the way north I have rushed the first stage of Act 3. In order to document the lighthouses I’ve visited I’ve enlisted the help of Elon Grok and A.I. Claude to help on these Lighthouse Stories. Despite their claims of infallibility I’ve found some of their facts not to be accurate and would welcome any corrections, which they will learn from! I have also sourced a few photos from the public domain (i.e. Dr Google) to compliment the shots I’ve taken on my travels. I would like to concentrate on telling my personal experiences and thoughts as I travel around and intend to reedit these lighthouse stories when I have time.