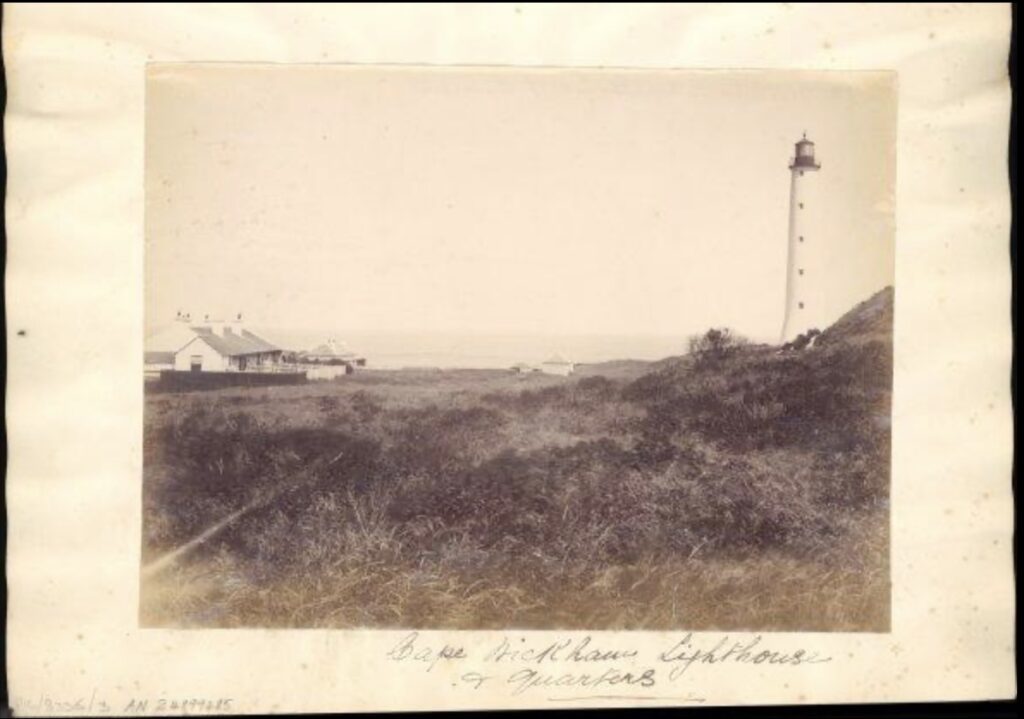

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is Australia’s tallest at 48 metres and stands on the windswept northern tip of King Island where the Southern Ocean collides with treacherous reefs and fierce currents of Bass Strait. Since it was first light on January 1, 1863, it has served as a vital navigational aid, guiding mariners through one of the world’s most dangerous passages. It also stands as a memorial to a dark history of shipwrecks, tragedies, and unsettling phenomena that have cemented King Island’s reputation as the “graveyard of Bass Strait.” Alongside the smaller Currie Harbour Lighthouse it remains a tied to tales of loss and mystery where the surrounding sea holds both its secrets and its mysteries.

The Palawa people, King Island’s original inhabitants long recognised Cape Wickham headland as a spiritual boundary, a place where the living interacted with their ancestral spirits. Their oral traditions warned of the sea’s hunger and spoke of “ghost ships” crewed by the lost which appearing in storms. European explorers and settlers soon learned the truth of these warnings as Bass Strait’s relentless gales and hidden reefs claimed countless vessels. King Island’s central position between mainland Australia and Tasmania combined with its low profile and surrounding shoals made it a deadly obstacle for mariners caught in poor weather and lacking precise charts.

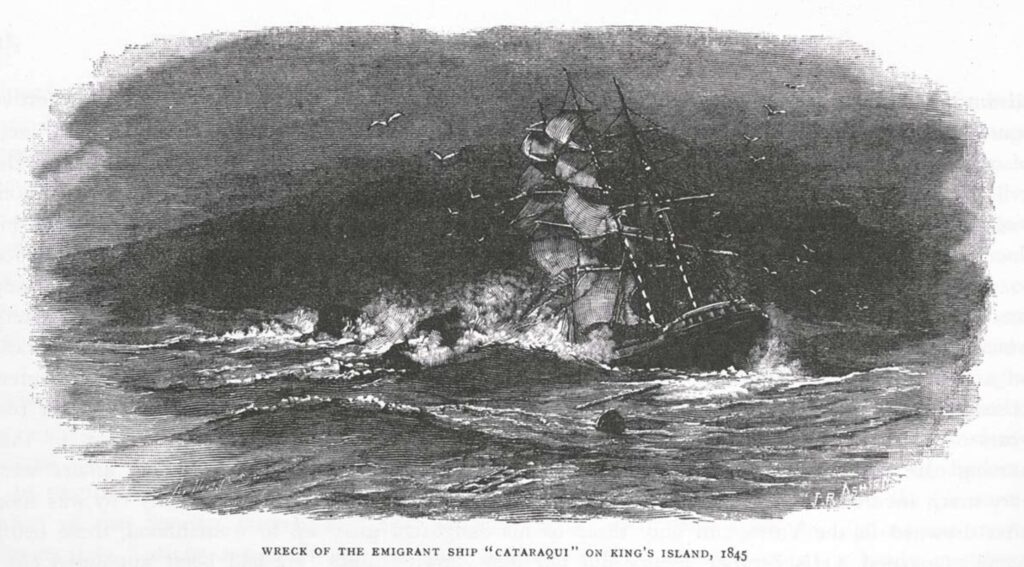

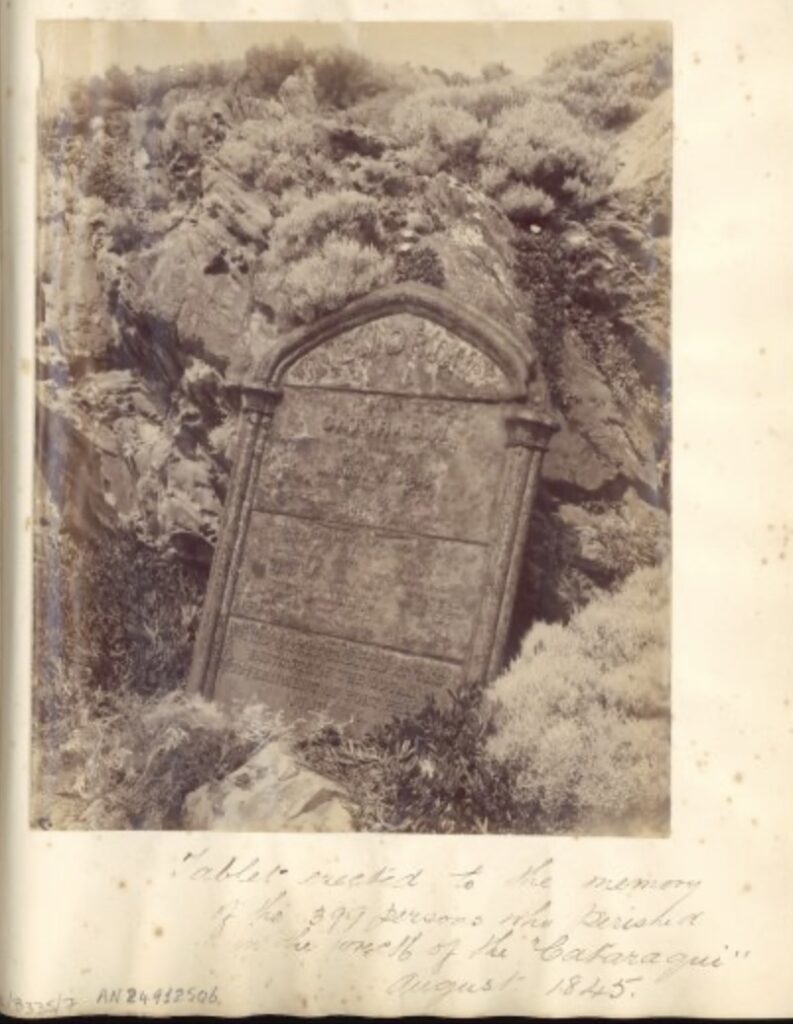

The need for a lighthouse became undeniable after the Cataraqui disaster on August 4, 1845, Australia’s worst civilian maritime tragedy. Carrying 367 passengers and crew from Liverpool to Melbourne the immigrant ship had struggled through Bass Strait’s gales for days with her captain unable to fix his position without celestial sightings. As the storm intensified the Cataraqui was driven onto reefs near what would later be Cape Wickham. The ship quickly broke up throwing men, women, and children into freezing waters where jagged rocks, fierce currents and towering waves offered no mercy. Of the 367 on board only nine survived, clinging to debris until dawn revealed a shore littered with bodies and wreckage. The loss of 358 lives sent shockwaves through colony and resulted in the authorities urgent approval for the construction of a lighthouse on Cape Wickham.

The Cataraqui was not the first to fall to King Island’s reefs, nor the last. In 1835, the Neva, a merchant vessel bound for Van Diemen’s Land struck Seal Rocks killing 224 passengers and crew, mostly women and children in conditions eerily similar to the later Cataraqui wreck. In 1858 the Shannon foundered claiming a further 60 lives. The schooner Blackwall was driven ashore in 1863, and the steamer Ly-ee-moon met its fate in 1886, each disaster reinforcing the island’s deadly reputation. Smaller vessels such as sealers’ and whalers’ boats vanished with distressing regularity their fates often unrecorded. Sealers reported finding fragments of timbers, personal belongings and human remains washed ashore after storms, silent evidence of ships lost without trace. These accounts, coupled with the Cataraqui’s horror spurred action and in 1861 construction began on Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

to the 358 souls lost in the Cataraqui disaster.

Building the lighthouse was a formidable challenge. The exposed headland offered no shelter from Bass Strait’s gales and the nearest fresh water was miles away. Every piece of equipment, building materials and supplies had to be transported from the mainland and across the islands treacherous terrain. Workers faced unstable ground that collapsed unexpectedly and weather that could turn deadly in minutes. Strange incidents plagued the project; tools disappeared only to reappear in odd places; materials were found arranged in geometric patterns overnight defying explanation. More unsettling were reports of voices calling workers’ names from empty cliffs or the sea below and sightings of figures in period clothing wandering the site at dawn then vanishing with the scent of seawater and decay. Construction foreman William Davies documented these occurrences, noting discoveries during foundation work; ships’ timbers, clothing, and personal effects from various eras suggesting Cape Wickham had claimed victims long before records began.

The most tragic incident occurred in 1862 when worker Michael O’Brien vanished during a routine shift. His body was found three days later at the base of the cliffs far from where colleagues said he had been working. His diary’s final entry read, “They don’t want us here. The sea keeps its own.” Workers whispered that the spirits of the wrecked opposed the lighthouse and were guarding a place where the sea held sway.

Despite these challenges the lighthouse was completed on the first day of 1863, its 1st Order Fresnel Lens casting a white flash every 7.5 seconds across 25 nautical miles. The first head keeper, Captain William Henderson arrived with his wife and three children unaware their new home was shared with unseen presences. Henderson’s logs soon recorded unusual events; the lighthouse mechanism malfunctioned on shipwreck anniversaries despite perfect maintenance and strange sounds emanated from within the tower: voices in unknown languages, ship’s bells ringing in empty chambers, and prayers echoing during storms. Keeper families reported children playing with “sea friends,” invisible companions who shared eerily accurate details of past wrecks, later verified as historical fact. Parents set extra places at meal tables, left doors unlocked during storms, and kept lamps burning in unused rooms, acknowledging the spirits they believed coexisted with them.

The lighthouse’s isolation fostered an environment where the physical and spiritual worlds seemed to merge. During severe storms keepers felt the presence of invisible crowds as if the spirits of those lost in the surrounding waters sought shelter. Water tanks sealed against contamination were found mixed with seawater containing relics like a child’s toy boat inscribed “Cataraqui”, Victorian-era jewellery and parchment fragments in scripts predating European settlement. The most chilling phenomenon was the phantom ships. Keeper James Morrison documented seven sightings of the Cataraqui’s ghostly wreck between 1875 and 1889, each replaying the disaster: a spectral vessel struggling through mountainous seas, passengers visible on deck, vanishing at the moment of impact. The Neva and Shannon appeared too, their final moments replayed with haunting precision. Unidentified vessels, their rigging suggesting wrecks from early European exploration materialised during gales, hinting at unrecorded losses.

Modernisation in the 1920s introduced radio equipment opening new channels for eerie communications. Keepers received distress calls from long lost ships, beginning with proper maritime protocol before dissolving into static filled with screams and crashing waves. In 1931 keeper Harold Mitchell logged a transmission: “Cape Wickham Light, this is Cataraqui, requesting immediate assistance, position five miles northwest of your station, taking on water fast…” The signal cut off abruptly, leaving an oppressive silence. Electrical systems flickered in patterns resembling maritime codes, spelling names of lost ships, and the lighthouse beam occasionally froze pointing at wreck sites.

As automation approached in 1992 supernatural activity intensified as if the spirits resisted the departure of human keepers. The final keeper, Robert MacDonald reported relentless phenomena; children’s laughter in empty rooms, the scent of pipe tobacco in abandoned spaces and dining tables set for unseen guests in locked rooms. His family awoke nightly to hymns sung by hundreds of voices in multiple languages while their dog howled at inaudible presences during storms. MacDonald’s last log entry read “The light will continue its vigil, but perhaps the time has come for the living to leave this place to those who came before us. They have been patient guardians, but their numbers grow with each passing storm.”

Automated in 1992 the lighthouse’s solar-powered light operates reliably yet crews report ongoing disturbances; tools move on their own, voices call from empty chambers, and figures in period clothing appear on the gallery. In 2003 a helicopter pilot saw people waving from the tower despite its unmanned status dressed in clothing from different eras as if representing all the disasters tied to King Island. Fishermen avoid Cape Wickham during wreck anniversaries reporting lights beneath the water tracing paths of lost ships most vivid during storms like those that caused the original wrecks.

The Currie Harbour Lighthouse built in 1879 on King Island’s west coast serves as a quieter counterpart. Its 21-metre cast iron tower painted white with a red lantern emits a white flash every 6 seconds visible for 14 nautical miles, guiding vessels to Currie’s port the island’s main settlement. Automated in 1989 it supports fishing and trade with fewer eerie tales than Cape Wickham, though local mariners occasionally speak of faint lights guiding them through fog as if the island itself watches over its people.

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is more than a navigational aid, it is a monument to lives lost and a testament to human efforts to tame Bass Strait. Its light guides ships past deadly reefs, honouring the past while warning the present as the sea remains a constant and unpredictable force of nature.

Technical Details:

First Exhibited: January 1, 1863

Status: Active (Automated 1992)

Location: Cape Wickham, King Island, Bass Strait

Construction: 1861-63. Cast iron tower with bluestone base

Tower Height: 48 metres (tallest lighthouse in Australia)

Focal Elevation: 60 metres above sea level

Original Optic: 1st Order Fresnel Lens

Range: 25 nautical miles

Character: Fl. W. 7.5s (white flash every 7.5 seconds)

Current Power Source: Solar panels with battery backup

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: Listed on Tasmanian Heritage Register