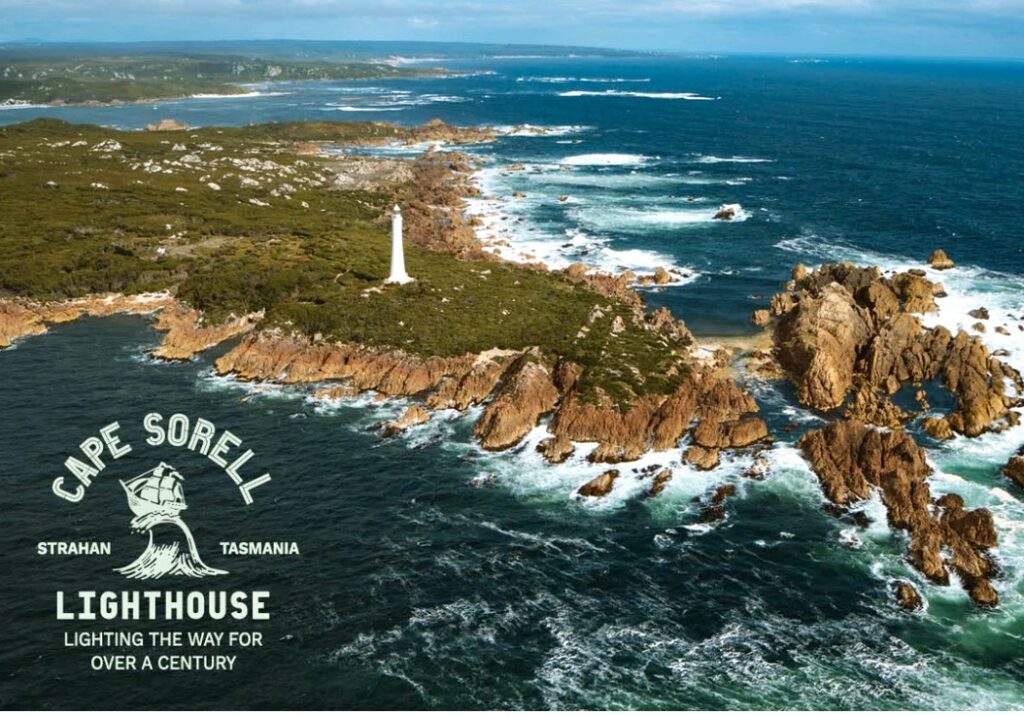

Cape Sorell lighthouse stands on one of Tasmania’s most exposed and treacherous headlands, marking the entrance to Macquarie Harbour halfway up the rugged west coast. Perched on a low headland rising from the Southern Ocean, this lighthouse has guided vessels through some of Australia’s most dangerous waters for over a century, bearing witness to countless tragedies and mysteries that have earned this stretch of coastline a reputation as the “skeleton coast” of Australia.

The cape itself isn’t overly spectacular but the coastline here is notorious for its ferocity, with the Southern Ocean’s full fury unleashed against Tasmania’s western coast. The area experiences some of the most severe weather conditions in the World, with howling westerly winds, driving rain, and mountainous seas that have claimed countless vessels over the centuries. Local Aboriginal peoples avoided this headland, believing it to be cursed by the spirits of those who had perished in its waters.

The need for a lighthouse at Cape Sorell became increasingly urgent as Tasmania’s west coast mining boom intensified in the late 19th century. Macquarie Harbour served as the vital lifeline for the remote mining settlements of Strahan and Queenstown, with steamers regularly navigating the treacherous harbour entrance known as “Hell’s Gates.”

The narrow, 120 metre wide entrance to Macquarie Harbour was given the name of Hells Gates by the convicts being transported to Sarah Island which was regarded as the harshest and most isolated prison in the colony. It could equally have been given this name by mariners trying to navigate this passage which is obstructed by hidden reefs and shoals and subject to fast running tides.

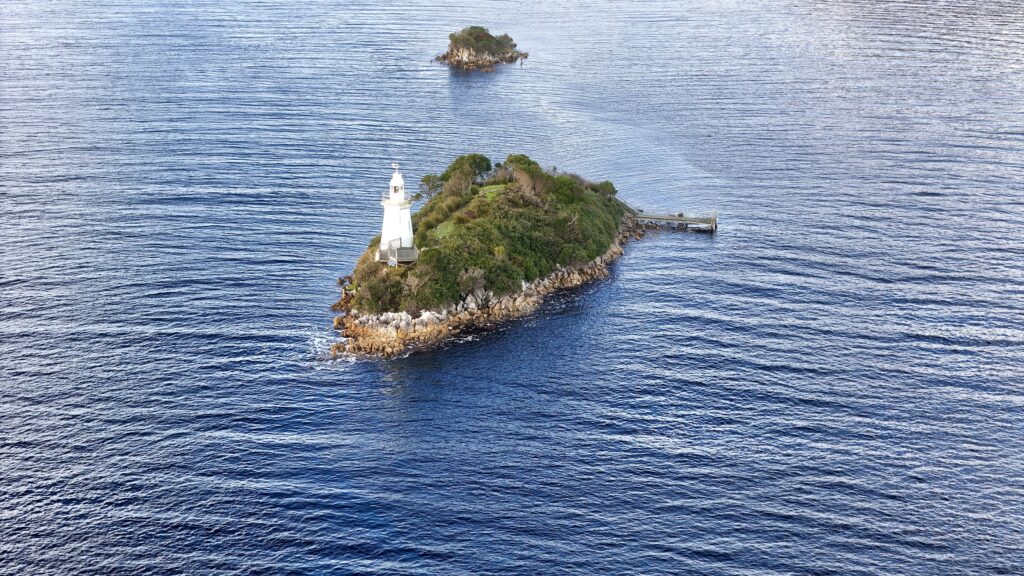

In 1892 lights were established on Entrance and Bonnet islands at Hell’s Gates but these were of little use to shipping at sea off the west coast. The installation of a coastal light together with improvements to the harbour such as a breakwater at Hell’s Gates was seen as a priority. The result was the establishment of a light at Cape Sorell, just outside Macquarie Harbour, in 1899.

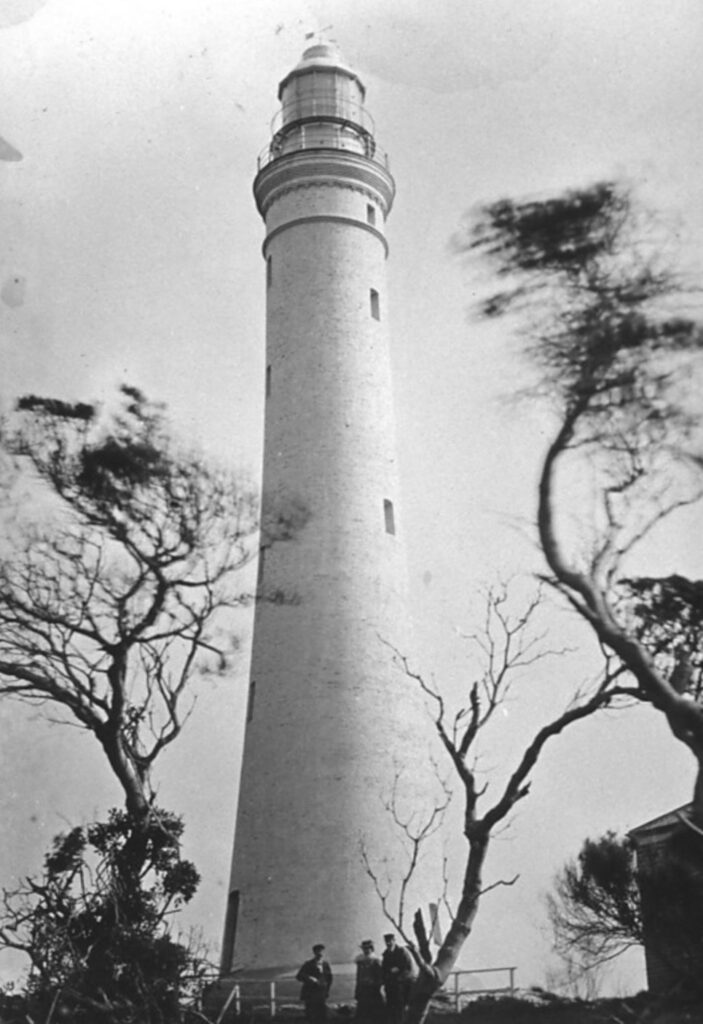

The lighthouse, which was named after the Lieutenant-Governor of Tasmania (1817-24) Colonel William Sorell is regarded as the most beautiful in Tasmania. The tower though slim and elegant has the strength to withstand the full force of the Roaring Forties and with an overall height of 37m it’s the second tallest in Tasmania with Cape Wickham on King Island being 11m higher standing at 48m.

However, the beauty of the lighthouse is matched by the sad history of shipwrecks and tragedies to those stationed at the lighthouse.

Perhaps the most notable loss was that of the “Strahan Belle” in 1887, carrying twenty-three miners and their families back to the mainland for Christmas. The ship vanished without trace during a sudden southwesterly gale, with only fragments of wreckage washing ashore weeks later. The lighthouse keepers who would later staff Cape Sorell claimed that on certain storm-lashed nights, they could hear the desperate cries of the Belle’s passengers carried on the wind, calling for help that would never come.

The decision to construct a lighthouse at Cape Sorell was made following this devastating loss, with the project assigned to the architectural partnership of Robert Huckson and Robert Hutchison and construction undertaken by J & R Duff Bros. who had already proven their expertise with other challenging Tasmanian lighthouses including the recently completed Maatsuyker Island station. Construction commenced in 1888, presenting immediate and severe logistical challenges that would test human endurance to its limits.

The construction crew faced constant danger from the unstable ground, savage weather, and the ever-present risk of being cut off from supplies by storms. The project was plagued by inexplicable accidents and strange occurrences that the workers attributed to the restless spirits of those who had perished in the surrounding waters. Tools would mysteriously disappear overnight, only to be found arranged in perfect circles the following morning. Workers reported hearing voices calling their names from empty buildings, and several men claimed to have seen figures in period clothing walking the shoreline at dawn, only to vanish when approached.

The most disturbing incident occurred in October 1898 when construction foreman Patrick O’Brien disappeared during a routine inspection of the foundation work. His body was found three days later at the base of the cliffs, despite colleagues insisting he had been nowhere near the edge when last seen. O’Brien’s final entry in the construction log, written the night before his death, simply stated: “They want us to leave. The sea remembers everything.”

Cape Sorell lighthouse was first exhibited on November 15th, 1899, its powerful beam cutting through the darkness to guide vessels safely past the treacherous reefs. The first head keeper, William Carmichael, arrived with his wife and two young children, beginning what would become one of Australia’s most challenging lighthouse postings. Carmichael’s early logbook entries document not only weather observations and shipping movements but also a series of strange phenomena that would plague the lighthouse throughout its operational life.

Within weeks of the light’s activation, Carmichael began reporting unusual occurrences in his official logs. The lighthouse’s clockwork mechanism would occasionally stop at precisely 11:47 PM, the estimated time of the Georgette’s sinking, despite being in perfect working order. More disturbing were the sounds that seemed to emanate from within the lighthouse tower itself: metallic scraping noises that resembled anchor chains being dragged across stone, and what Carmichael described as “the sound of many voices singing hymns in languages I do not recognise.”

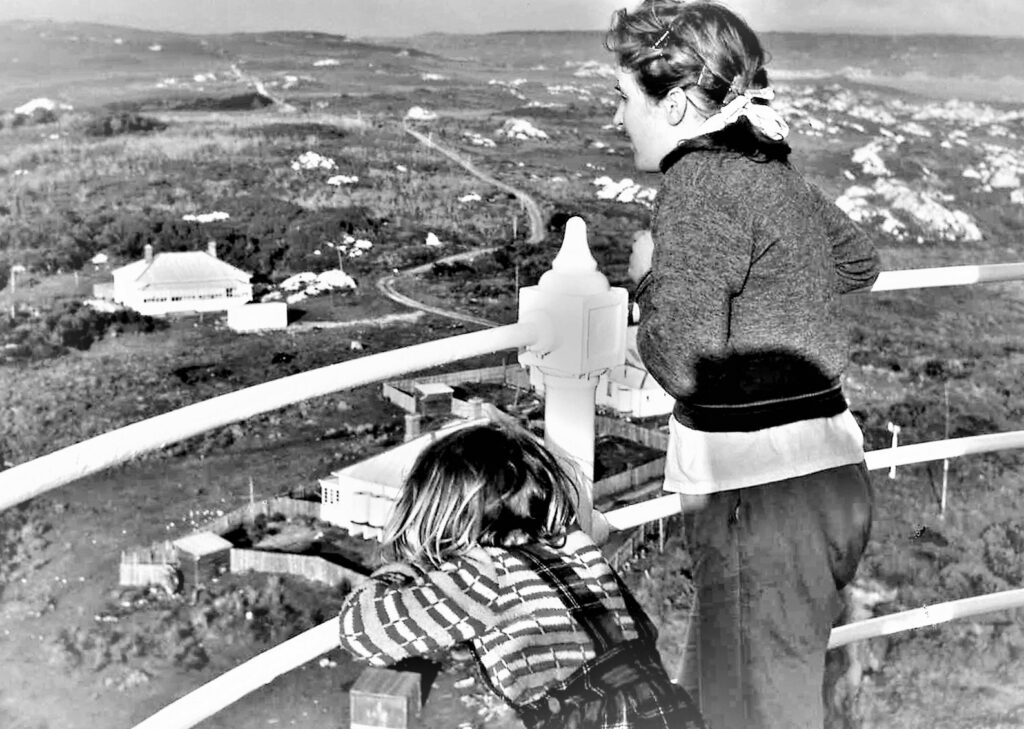

Life at Cape Sorell tested the limits of human endurance and adaptability. The station’s extreme isolation meant that keeper families could be cut off from the outside world for months at a time when severe weather prevented supply vessels from approaching. The keepers developed remarkable self-sufficiency, maintaining vegetable gardens in sheltered pockets behind the cottages and keeping livestock despite the challenges posed by the harsh environment and the strange incidents that seemed to plague the station.

Tragedy struck the lighthouse community in 1903 when assistant keeper Thomas Brennan was found dead in the lantern room under mysterious circumstances. Brennan had been performing routine maintenance on the lens assembly when he apparently fell from the catwalk, suffering fatal injuries. However, his colleague Edward Walsh reported that Brennan had been secured by safety ropes and questioned how such an experienced keeper could have suffered such an accident. More puzzling was Walsh’s claim that moments before discovering Brennan’s body, he had heard multiple voices engaged in heated conversation coming from the lantern room, though when he investigated, only Brennan was present, and already deceased.

The lighthouse keepers became expert weather observers, their daily recordings providing crucial data for maritime forecasting services. Their logbooks document wind speeds that regularly exceeded 150 kilometres per hour, with one entry from keeper James Morrison in 1923 recording a gust of 189 kilometres per hour that reportedly lifted sheep from their feet and hurled them over the cliff edge. During this same storm, Morrison reported seeing what he described as “a great sailing ship with torn sails” battling through the massive waves below the lighthouse, despite no vessels being scheduled in the area. When he attempted to signal the ship with the lighthouse beam, it simply vanished into the storm.

The mystery of the phantom ships became a recurring theme in the keeper’s logs. In 1931, keeper Harold Davies documented seven separate sightings of vessels that appeared to be in distress, yet when he attempted to radio coastal authorities, no ships were reported missing. Davies became convinced that he was witnessing the ghostly reenactments of historical wrecks, writing in his personal diary: “The sea gives up its dead on certain nights, and we are condemned to watch their final voyages played out again and again.”

Water supply was a constant concern, with rainwater collected from every available surface and stored in large tanks that were frequently damaged by flying debris during storms. In 1925, keeper Michael O’Sullivan made a disturbing discovery when cleaning the main water tank. At the bottom, he found a collection of objects that had no explanation for their presence: a child’s leather boot dating from the 1870s, several pieces of ship’s crockery bearing the name “Georgette,” and most unsettling of all, a brass nameplate reading “Strahan Belle” despite that vessel having been lost at sea decades earlier.

The isolation fostered strong bonds among the lighthouse families, though these relationships were often strained by the unexplained phenomena that seemed to intensify during the long winter months. Children born on the cape grew up accepting the strange occurrences as part of daily life, often playing games that involved “talking to the sea people”—invisible playmates that concerned their parents but seemed harmless enough. However, in 1934, the daughter of keeper Robert MacDonald disappeared for three days during a severe storm. When she was finally found, unharmed but soaking wet, in a sea cave at the base of the cliffs, she claimed that “the lady in the white dress” had kept her safe and warm. The cave was only accessible at low tide, and the girl had no explanation for how she had survived three days of pounding surf without injury.

The most documented supernatural incident in the lighthouse’s history occurred during the winter of 1942, when head keeper Arthur Fleming and his assistant Samuel Brooks reported a series of events that defied rational explanation. Over the course of a week, both men witnessed what they described as a full-scale naval battle being fought in the waters below the lighthouse. They documented ships firing cannons, men shouting orders, and the screams of the wounded, yet when they searched the waters with binoculars, nothing was present except empty ocean. The phantom battle always began at sunset and concluded at precisely 11:47 PM, leaving both keepers exhausted and disturbed by what they had witnessed.

Technological improvements over the decades brought some comfort to the keeper families, though they also seemed to intensify the supernatural activity. The installation of radio communication equipment in the 1930s provided the first reliable means of contact with the outside world, but keepers frequently reported receiving transmissions from vessels that had been lost decades earlier. In 1938, keeper William Stone documented receiving a distress call that began: “This is the Strahan Belle, taking on water fast, position approximately five miles southwest of Cape Sorell…” Stone attempted to respond, but the transmission cut off abruptly, leaving only static.

Electric power arrived at Cape Sorell in 1938 with the installation of diesel generators, transforming both the lighthouse operation and the daily lives of the keeper families. However, the electrical systems seemed particularly susceptible to the mysterious forces that haunted the station. Lights would flicker in patterns that resembled maritime signal codes, and the generators would occasionally start themselves in the middle of the night, despite being properly shut down. Most unsettling was the tendency for electrical equipment to malfunction during the anniversary dates of major shipwrecks in the area.

The final tragedy to befall Cape Sorell lighthouse occurred in 1987, just seven years before automation. Relief keeper David Patterson arrived at the station to find head keeper Martin Walsh and his family had vanished without explanation. Their personal belongings remained undisturbed, meals were still on the table, and the lighthouse had continued to operate normally. An extensive search of the island revealed no trace of the Walsh family, and the mystery was never solved. Patterson, who had to maintain the lighthouse alone until a replacement crew could be arranged, reported constant supernatural activity during his two-week vigil, including the sound of children playing in the empty cottages and the distinct aroma of his predecessor’s pipe tobacco drifting through rooms that had been sealed for days.

Cape Sorell lighthouse was automated in 1994, ending over a century of continuous human habitation on this remote and haunted headland. The final keeper, Thomas Wright, had requested an early transfer after experiencing what he described as “an overwhelming presence” that made normal life impossible. His final log entry, dated March 15th, 1994, read: “The light will continue, but perhaps it’s time for the living to leave this place to those who came before.”

Since automation, the lighthouse has operated with remarkable reliability despite the continuing challenges posed by both the harsh environment and the unexplained phenomena that persist in the area. Maintenance crews who visit the station by helicopter report a range of supernatural encounters, from tools that move on their own to the sound of lighthouse bells that were removed decades ago. In 2003, a helicopter pilot reported seeing figures in period clothing waving from the lighthouse gallery, though the station had been unmanned for nearly a decade.

Today, Cape Sorell lighthouse continues to serve as a vital navigation aid for vessels approaching Macquarie Harbour and the west coast of Tasmania. The beacon continues its nightly vigil, warning mariners of the hidden dangers that lurk beneath the waters around this unforgiving coast, while the restless spirits of those claimed by these treacherous waters maintain their own eternal watch. Local fishermen still avoid the area on certain nights, particularly during storm seasons, when the phantom lights of long-lost vessels are said to dance in the waters below the lighthouse, forever attempting to reach a safety that will always remain just beyond their grasp.

There are several smaller lights located further up the west coast at Sandy Cape, which just south of Arthur River and Bluff Hill Point and the original but now demolished eponymously named Lighthouse Beach lighthouse which are both between Arthur River an Marrawah.

Technical Details:

First Exhibited: November 15, 1899

Architects: Robert Huckson & Robert Hutchison

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: 42°12’S, 145°09’E

Original Optic: 1st Order Fresnel Lens

Current Optic: LED Array

Automated: March 1994

Construction: Brick with local quartzite stone foundations

Height: 37 metres

Elevation: 70 metres above sea level

Range: Nominal: 25 NM, Geographical: 27 NM

Character: Fl. W. 15s

Light Source: LED

Power Source: Solar/Wind Hybrid System

Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Thanks Mike. Another beauty!

Piet