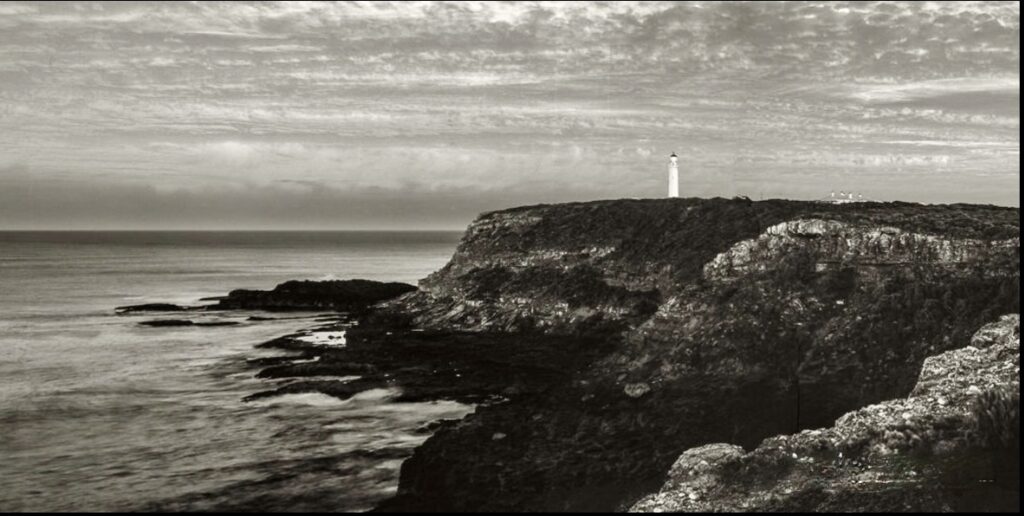

Cape Nelson Lighthouse, Victoria’s westernmost sentinel commanding the approaches to Bass Strait from its dramatic clifftop position, stands as a monument to colonial perseverance after construction delays spanning nearly two decades before its first illumination on July 7, 1884. This distinctive white masonry tower, distinguished by its red band and surrounded by the longest stone boundary wall of any Australian lighthouse, rises from the windswept headland 15 kilometres southwest of Portland, where it has guided mariners around the treacherous cape that marks the transition from the Southern Ocean to Bass Strait. The lighthouse’s remote and exposed position on these rugged volcanic cliffs subjects it to the full fury of Southern Ocean storms, making it both a crucial navigation aid and a testament to the engineering skill required to construct substantial masonry buildings in such challenging conditions.

Cape Nelson itself presents a forbidding landscape of towering sea cliffs, native scrubland, and pounding surf, where the Southern Ocean meets Bass Strait in a confusion of currents, reefs, and unpredictable weather that has challenged mariners since the earliest days of European exploration. The cape’s volcanic origins created a coastline of dark basalt cliffs rising directly from deep water, offering no shelter for vessels caught in storms but providing an ideal foundation for a lighthouse that needed maximum visibility across both western and northern approaches. The 243-hectare state park that now surrounds the lighthouse preserves this wild coastal environment, where native vegetation adapted to salt spray and constant winds creates a unique ecosystem supporting diverse bird species and seasonal whale migrations.

The Gunditjmara people, whose traditional country encompasses the Portland region and Cape Nelson, possessed intimate knowledge of this treacherous coastline through thousands of years of seasonal occupation, their understanding of weather patterns, marine resources, and dangerous sea conditions proving invaluable to early European mariners attempting to navigate these waters. Their sophisticated aquaculture systems in the region’s wetlands and their detailed knowledge of seasonal fish runs and bird migrations reflected a deep connection to the marine environment that European settlers struggled to understand. The establishment of the Framlingham Mission disrupted traditional Gunditjmara life, but their cultural heritage endures in the landscape around Cape Nelson, where archaeological sites and traditional stories preserve their connection to this dramatic coastline.

The urgent need for a lighthouse at Cape Nelson became apparent with the establishment of Portland as Victoria’s first permanent settlement in 1834 and the subsequent growth of maritime traffic seeking the protection of Portland Bay while avoiding the dangerous waters that extend far offshore from the cape itself. Early vessels approaching from the west faced the challenge of identifying Cape Nelson among the similar headlands of the region, particularly during the thick fogs that frequently shroud this coast, while strong currents and hidden reefs created additional hazards for sailing ships attempting to round the cape in heavy weather. The increasing size and number of vessels using the Portland route to Melbourne made reliable navigation aids essential, though the remote location and construction challenges delayed the lighthouse’s establishment for nearly 25 years after initial proposals.

The extended construction period of Cape Nelson Lighthouse, from initial planning in the 1860s through to completion in 1884, reflected both the site’s challenging conditions and the difficulty of obtaining suitable building materials for such an exposed location. Colonial engineers recognised that any structure on Cape Nelson would face extreme weather conditions requiring exceptional durability, leading to specifications for massive bluestone masonry that could withstand decades of salt spray and storm damage. The difficulty in obtaining suitable bluestone delayed construction repeatedly, as quarries struggled to provide stones of sufficient size and quality for the demanding coastal environment, while transportation of materials to the remote site required careful planning to coordinate with weather windows and tidal conditions.

Construction finally commenced in the late 1870s under contractor J. Thorne, working from designs prepared by the Public Works Department that incorporated lessons learned from earlier lighthouse projects around Bass Strait. The circular stone tower, built from carefully selected bluestone blocks, required foundations excavated directly into the volcanic rock of the cape to ensure stability against the enormous forces generated by Southern Ocean storms. The lighthouse keepers’ quarters, constructed simultaneously from matching bluestone, provided accommodation for multiple families in a complex that included workshops, stores, and all the facilities necessary for self-sufficient operation in such an isolated location.

The lighthouse’s most distinctive feature, beyond the tower itself, is the remarkable stone boundary wall that extends for over a kilometre around the entire lighthouse reserve, built to a height of 1.75 metres and width of 0.4 metres from the same bluestone as the main structures. This wall, unique among Australian lighthouses, served multiple purposes: defining the government reserve, providing windbreak protection for the keepers’ gardens and livestock, and creating a firebreak that could protect the buildings from grass fires that periodically swept the cape. The wall’s construction required an enormous quantity of stone and represented a substantial investment in creating a self-contained lighthouse station capable of withstanding both natural disasters and complete isolation from outside assistance.

The lighthouse entered service on July 7, 1884, its first-order Fresnel lens system representing the most advanced optical technology available, capable of projecting a powerful beam across both the western approaches from the Southern Ocean and the northern waters of Bass Strait. The fixed white light, varied by red sectors to indicate dangerous areas, provided mariners with precise positional information essential for safe navigation around the cape’s treacherous reefs and currents. The lighthouse keepers, initially housed in the five cottages built within the stone-walled compound, maintained not only the light itself but also the complex systems of oil storage, lens cleaning, and weather observation that made the station fully self-sufficient.

The operational history of Cape Nelson Lighthouse spans 140 years of continuous service, during which the isolated station evolved from complete dependence on irregular supply ships to eventual road access and modern communication systems. The lighthouse families developed extensive gardens within the protective stone walls, raised livestock, and created a small community that endured the psychological challenges of extreme isolation while maintaining one of Australia’s most important navigation aids. The station’s logbooks record not only routine maintenance and weather observations but also dramatic rescues, shipwreck investigations, and the gradual technological transitions that eventually eliminated the need for resident keepers.

The lighthouse’s conversion to automated operation reflected broader changes in navigation technology and lighthouse management, with the last resident keepers departing in the latter part of the 20th century after generations of families had called Cape Nelson home. The five keepers’ cottages, rather than being demolished or abandoned, found new life as unique tourist accommodation, allowing visitors to experience the lighthouse station’s remarkable setting while supporting ongoing conservation of the heritage buildings and surrounding landscape.

Modern Cape Nelson Lighthouse continues operating as an active navigation aid under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, its LED beacon powered by solar panels maintaining the tradition of guidance that began in 1884. The lighthouse station has evolved into one of Australia’s most distinctive heritage tourism destinations, where visitors can stay in the original keepers’ cottages, explore the dramatic coastal landscape, and experience the isolation and natural beauty that defined lighthouse life for over a century.

The surrounding Cape Nelson State Park protects 243 hectares of native coastal vegetation and provides habitat for diverse wildlife, while the Sea Cliff Nature Walk offers spectacular views along some of Victoria’s most dramatic coastline. The park’s position on major bird migration routes makes it a premier birdwatching destination, while seasonal whale migrations provide opportunities to observe southern right whales and humpback whales from the lighthouse’s commanding clifftop position.

Conservation efforts focus on maintaining the heritage values of the lighthouse complex while adapting the buildings for sustainable tourism use that supports ongoing maintenance of these remarkable structures. The stone boundary wall, keepers’ cottages, and lighthouse tower represent one of Australia’s most complete 19th-century lighthouse stations, demonstrating both the engineering challenges of remote lighthouse construction and the self-sufficient lifestyle required of lighthouse families.

The lighthouse’s survival in virtually original condition, combined with its continued operation as a navigation aid and successful adaptation as tourist accommodation, makes Cape Nelson Lighthouse a model for heritage lighthouse conservation. Its remote location, which once made it one of Australia’s most isolated lighthouse stations, now provides visitors with an authentic experience of lighthouse life while preserving the wild coastal environment that makes Cape Nelson one of Victoria’s most spectacular natural landmarks.

Technical Specifications – Cape Nelson Lighthouse

First Exhibited: July 7, 1884

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Cape Nelson, near Portland, Victoria, Australia (Latitude 38° 25′ south, Longitude 141° 35′ east)

Construction: 1876-1884, contractor J. Thorne, Public Works Department design

Tower Height: 21 metres

Focal Elevation: Approximately 65 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Bluestone masonry

Original Optic: First-order Fresnel lens with fixed light and red sectors

Current Light: LED beacon powered by solar panels

Character: Fixed White Light with red sectors

Range: Nominal range approximately 19 nautical miles

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: Listed on Victorian Heritage Register

Disclaimer: Due to the need to get across the “Top End” in the dry season (which usually ends in October), and to spend time in the outback on the way north I have rushed the first stage of Act 3. In order to document the lighthouses I’ve visited I’ve enlisted the help of Elon Grok and A.I. Claude to help on these Lighthouse Stories. Despite their claims of infallibility I’ve found some of their facts not to be accurate and would welcome any corrections, which they will learn from! I have also sourced a number of photos from the public domain (i.e. Dr Google) to compliment the shots I’ve taken on my travels. I would like to concentrate on telling my personal experiences and thoughts as I travel around and intend to reedit these lighthouse stories when I have time