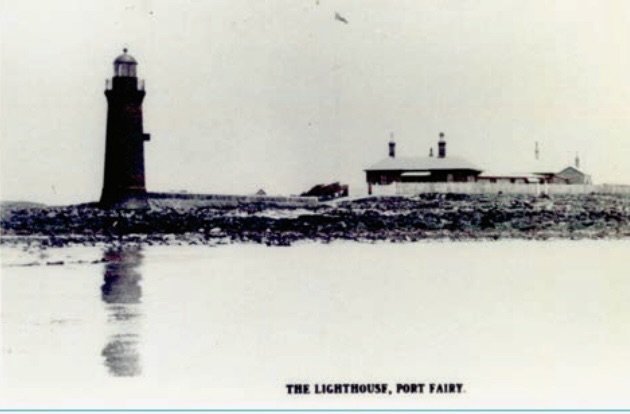

Griffiths Island Lighthouse, rising from the wind-swept shores of a small island at the mouth of the Moyne River in Port Fairy, Victoria, stands as a distinctive sentinel marking one of Australia’s most historic fishing ports. This unique 11-metre bluestone tower, built at sea level rather than on commanding heights like most coastal lighthouses, has guided vessels through the treacherous river entrance and into Port Fairy’s protected harbour since 1859. Connected to the mainland by a causeway that disappears at high tide, the lighthouse occupies a strategic position where Bass Strait’s unpredictable waters meet the narrow Moyne River channel, making it an essential navigation aid for the western Victorian coast’s most important 19th-century trading port.

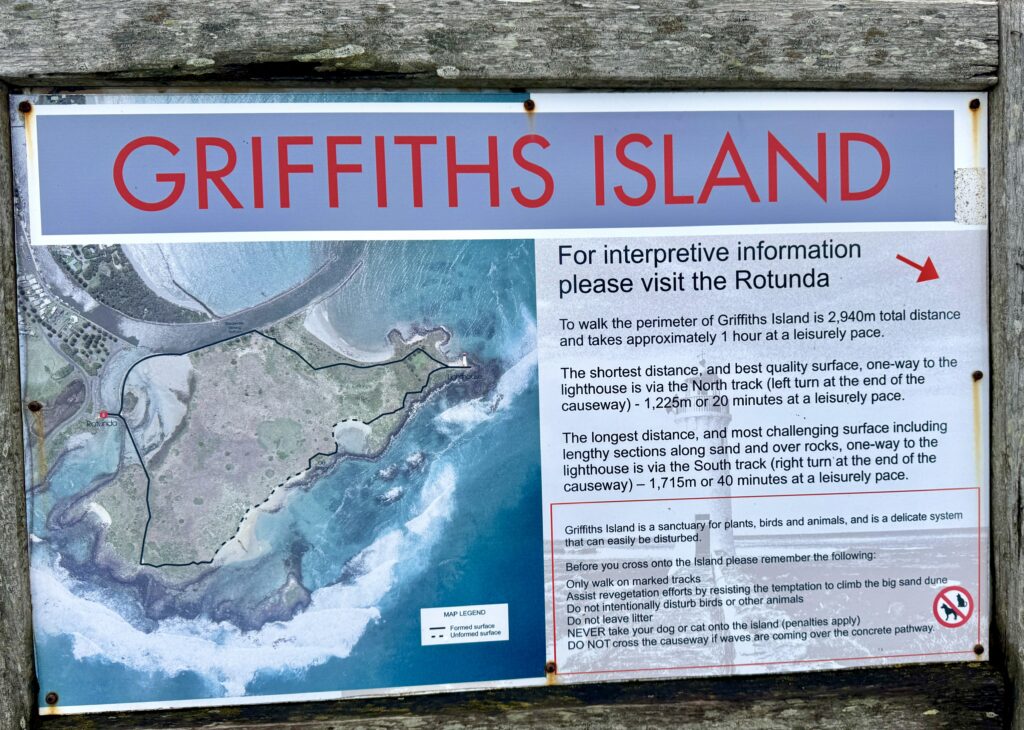

The island itself presents a remarkable landscape of native vegetation, walking tracks, and wildlife, where swamp wallabies graze among tea trees and thousands of short-tailed shearwater seabirds return annually to nest in burrows across the 8-hectare reserve. Griffiths Island’s low-lying topography, barely above sea level, creates a unique microenvironment where coastal scrub meets river estuary, providing habitat for diverse bird species while exposing the lighthouse to the full force of Southern Ocean storms. Unlike the dramatic cliff-top positions of most Australian lighthouses, this structure’s sea-level location made it particularly vulnerable to wave damage and storm surge, requiring robust bluestone construction to withstand nearly 170 years of battering from Bass Strait’s notorious weather.

The Gunditjmara people, traditional custodians of this southwestern Victorian coastline, have inhabited the area around Port Fairy for thousands of years, their sophisticated aquaculture systems and permanent settlements reflecting a deep understanding of the coastal and riverine environment. Their knowledge of the treacherous Moyne River bar, where fresh water meets the sea creating dangerous cross-currents and shifting sandbars, proved invaluable to early European settlers and mariners. The island, known to the Gunditjmara by its traditional name, held significance as a seasonal fishing and gathering place, with archaeological evidence of middens and tool-making sites scattered across its surface. European colonisation disrupted these ancient patterns, but the Gunditjmara connection to country endures, with their maritime expertise recognised as contributing to the safe navigation of these waters long before any lighthouse existed.

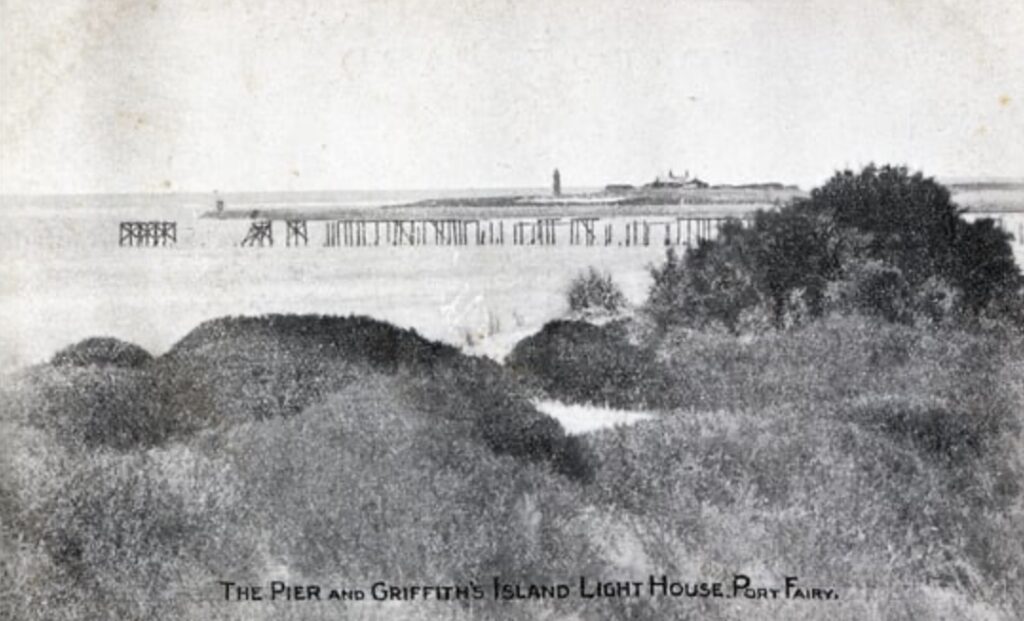

The urgent need for a navigation aid at Port Fairy emerged as the town developed into western Victoria’s premier port during the 1840s and 1850s, with the Moyne River entrance claiming numerous vessels attempting to reach the harbour’s safety. The treacherous river bar, where sand and silt deposits constantly shifted under tidal action, created a shallow, narrow channel that could trap unwary mariners, particularly during rough weather when waves broke across the entrance. Early trading vessels, whalers, and later gold rush traffic faced the challenge of identifying the river mouth among the similar-looking coastline stretches, with many ships running aground on the bar or missing the entrance entirely in fog and storms. The port’s growing importance as a wool, grain, and passenger terminal—with regular services to Melbourne, Adelaide, and Tasmania—made reliable navigation essential, while the increasing size of steam vessels demanded precise channel guidance that only a lighthouse could provide.

Construction of Griffiths Island Lighthouse commenced in 1859 as part of the Victorian Public Works Department’s ambitious program to establish four harbour lights across the colony, with Scottish stonemasons selected for their expertise in working the local bluestone quarried from the volcanic plains surrounding Port Fairy. The challenging island location required all materials and workers to be transported across the causeway during low tide or ferried by small boats in rough conditions, with the bluestone blocks carefully shaped and fitted using traditional dry-stone techniques that required no mortar between courses. The tower’s unique design incorporated an internal spiral staircase cut directly into the stone walls, with each step inserted into the next course during construction—a distinctive engineering solution that eliminated the need for a separate central support column while maximizing the structure’s strength against storm forces.

The lighthouse’s unusual sea-level position, dictated by the flat topography of Griffiths Island, presented unique challenges that required innovative solutions from the colonial engineers. Unlike cliff-top lighthouses that gained height and range from elevation, the Griffiths Island beacon relied entirely on its 11-metre tower height to achieve visibility over the surrounding coastline and provide adequate warning range for approaching vessels. The bluestone construction, with walls tapering from a broad base to support the lantern room, demonstrated remarkable durability in withstanding nearly two centuries of salt spray, storm surge, and the occasional high tide that completely surrounded the structure. Scottish craftsmanship ensured precise stonework that has required minimal maintenance, with the original bluestone showing little weathering despite constant exposure to Bass Strait’s harsh marine environment.

Griffiths Island Lighthouse entered service in 1859, its fixed white light burning whale oil in a Fresnel lens system that cast its beam across the Moyne River entrance and surrounding waters to guide vessels safely through the treacherous bar. The lighthouse keepers and their families faced unique challenges living on an island that became completely cut off during high tides and severe weather, with supplies and communication dependent on small boats or timing trips across the exposed causeway. The keeper’s cottage, built simultaneously with the lighthouse from matching bluestone, provided basic accommodation for the lighthouse family, though the isolation proved demanding for wives and children who might be stranded for days during storms when the causeway disappeared beneath churning waters.

The operational history of Griffiths Island Lighthouse reflects the changing fortunes of Port Fairy as a major port, with the light serving increasing numbers of coastal steamers, wool clippers, and immigrant ships during the 1860s-1880s boom period before declining traffic reduced its importance in the early 20th century. Lighthouse keepers maintained detailed logbooks recording weather conditions, vessel movements, and the constant battle against salt corrosion that threatened the delicate lens mechanisms and metalwork of the lantern room. Automation gradually replaced the resident keepers, with the last permanent lighthouse keeper departing in the mid-1950s after nearly a century of continuous habitation, though maintenance crews continued visiting regularly to service the increasingly sophisticated navigation equipment.

The lighthouse’s conversion to automatic operation reflected broader changes in marine navigation technology, with electric power replacing oil flames and eventually solar panels providing sustainable energy for the modern LED beacon. The Haldane Brothers, who served as lighthouse keepers in the 1930s, built the fishing boat “Amaryllis” on Griffiths Island for their personal use, illustrating the self-reliant lifestyle required of lighthouse families. Despite automation, the structure continues functioning as an active navigation aid, its distinctive fixed white light still guiding vessels through the Moyne River entrance, though modern GPS systems have reduced its critical importance for contemporary mariners.

Today, Griffiths Island Lighthouse stands as both a working navigation aid and a significant heritage site, protected on the Victorian Heritage Register for its historical importance as the only surviving harbour light from the original 1859 construction program still in its original location. The lighthouse and island have become a popular tourist destination, accessible via a scenic 400-metre walking track that showcases the unique coastal environment and provides spectacular views across Bass Strait and the Southern Ocean. The National Trust of Australia conducts guided tours of the lighthouse, weather permitting, allowing visitors to climb the bluestone tower and experience the panoramic views that lighthouse keepers enjoyed for nearly a century.

The island’s transformation into a nature reserve has created opportunities for wildlife observation, particularly during the annual shearwater migration when thousands of seabirds return to their nesting burrows in a spectacular natural display that draws visitors from across Victoria. The resident swamp wallaby population, unique for such a small coastal island, adds to the attraction while demonstrating the ecosystem’s resilience despite human intervention. Conservation efforts focus on protecting both the cultural heritage values of the lighthouse complex and the natural environment that makes Griffiths Island a crucial seabird breeding sanctuary.

Port Fairy’s designation as a National Trust Historic Town recognises the broader maritime heritage context in which Griffiths Island Lighthouse played a vital role, with the port’s collection of 19th-century buildings, wharves, and maritime infrastructure creating one of Australia’s most complete historic coastal settlements. The lighthouse serves as a tangible link to the era when Port Fairy ranked among Australia’s busiest ports, handling wool exports, passenger services, and general cargo that connected western Victoria to Melbourne and the wider world. Its survival in original condition, when most contemporary harbour lights have been demolished or relocated, makes it an invaluable resource for understanding 19th-century lighthouse technology and the crucial role of navigation aids in colonial maritime development.

The ongoing maintenance of Griffiths Island Lighthouse by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority ensures its continued operation as an active navigation aid while preserving its heritage values for future generations. Modern LED technology provides reliable illumination with minimal power consumption from solar panels, eliminating the need for regular fuel deliveries that once challenged lighthouse keepers. The structure’s remarkable durability, evidenced by minimal structural deterioration after 165 years of continuous operation, demonstrates the quality of both the Scottish stonemasons’ craftsmanship and the colonial engineers’ design that successfully adapted lighthouse technology to the unique challenges of a sea-level harbour light.

Technical Specifications

First Exhibited: 1859

Status: Active (Automated)

Location: Griffiths Island, Port Fairy, Victoria, Australia (Latitude 38° 23′ south, Longitude 142° 14′ east)

Construction: 1859, Victorian Public Works Department

Tower Height: 11 metres

Focal Elevation: 11 metres above sea level

Construction Material: Bluestone (local volcanic stone)

Original Optic: Fresnel lens system with whale oil burner

Current Light: LED beacon powered by solar panels

Character: Fixed White Light

Range: Nominal range approximately 8 nautical miles

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Heritage Status: Listed on Victorian Heritage Register (H1659)

Notable Features: Only surviving 1859 harbour light in original location; unique sea-level position; distinctive bluestone construction with integral spiral staircase

Disclaimer: Due to the need to get across the “Top End” in the dry season (which usually ends in October), and to spend time in the outback on the way north I have rushed the first stage of Act 3. In order to document the lighthouses I’ve visited I’ve enlisted the help of Elon Grok and A.I. Claude to help on these Lighthouse Stories. Despite their claims of infallibility I’ve found some of their facts not to be accurate and would welcome any corrections, which they will learn from! I have also sourced a number of photos from the public domain (i.e. Dr Google) to compliment the shots I’ve taken on my travels. I would like to concentrate on telling my personal experiences and thoughts as I travel around and intend to reedit these lighthouse stories when I have time.