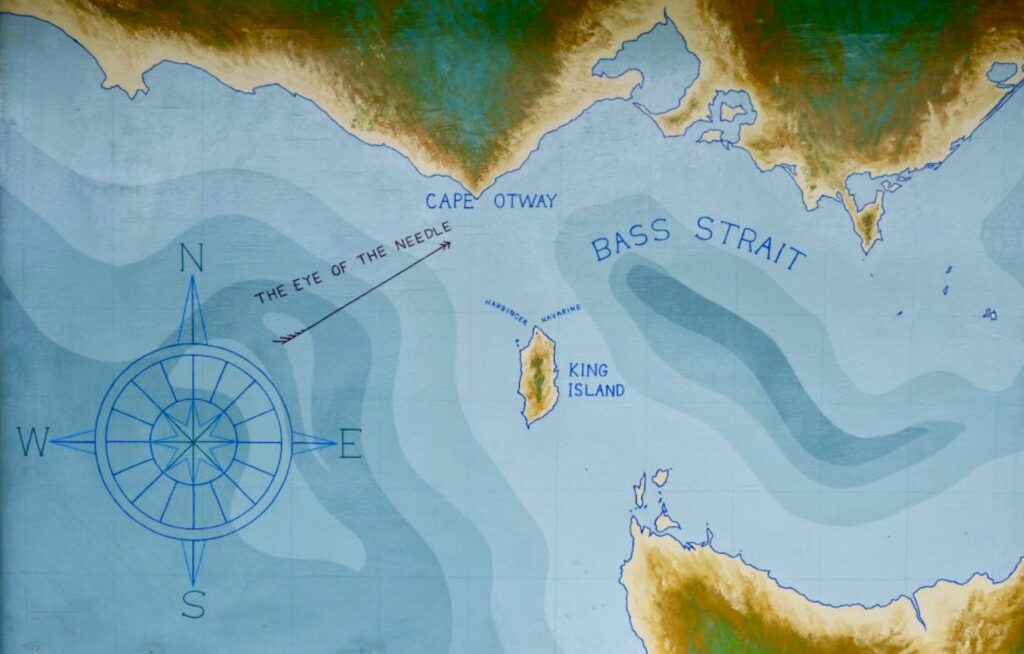

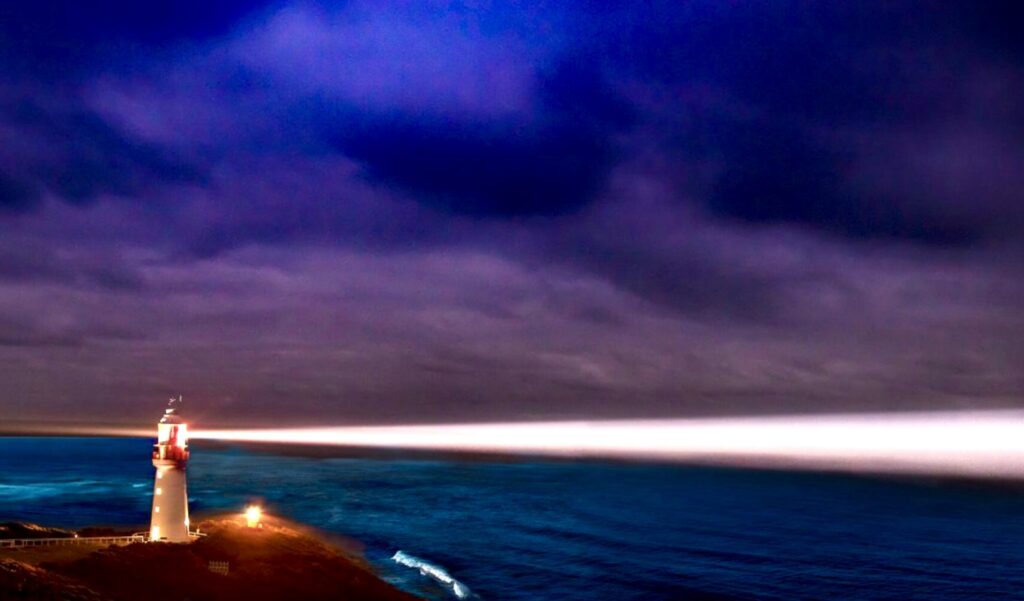

The Cape Otway Lighthouse located above the rugged cliffs of Cape Otway along Victoria’s Great Ocean Road is Australia’s oldest surviving mainland lighthouse, operational since 1848. Positioned at the the narrow western entrance to Bass Strait where it meets the Southern Ocean this treacherous passage was given the name the “Eye of the Needle” by early mariners bound for Melbourne and Australia’s east coast. The 21 metre sandstone tower that stands 91 metres above sea level, has helped guide seafarers along what became known as the Shipwreck Coast due to the number of ships lost to the deadly combination of fog, gales, submerged reefs, unpredictable currents, and sudden squalls all of which are common along this stretch of coast, justifying its reputation as a maritime graveyard.

The cape consists of steep cliffs, dense rainforests, and rough seas, shaped by strong winds and large waves hitting hidden reefs offshore. Bass Strait, separating mainland Australia from Tasmania, is known for dangerous conditions like fog, storms, and fast tides. During the 19th-century gold rush this route saw heavy shipping traffic to Melbourne, but reefs and limited navigation aids led to over 200 wrecks along the Victorian coast by the late 1800s.

The Gadubanud people, traditional custodians of the Otway Ranges and coast, have lived here for thousands of years, with a deep connection to the land and sea. Their traditions highlight the area’s significance their knowledge of the surrounding country assisted early European explorers, including Charles La Trobe, who selected the lighthouse site in 1846. European settlement disrupted their way of life, but their heritage endures, with traditional meeting huts at the lighthouse site honouring their history.

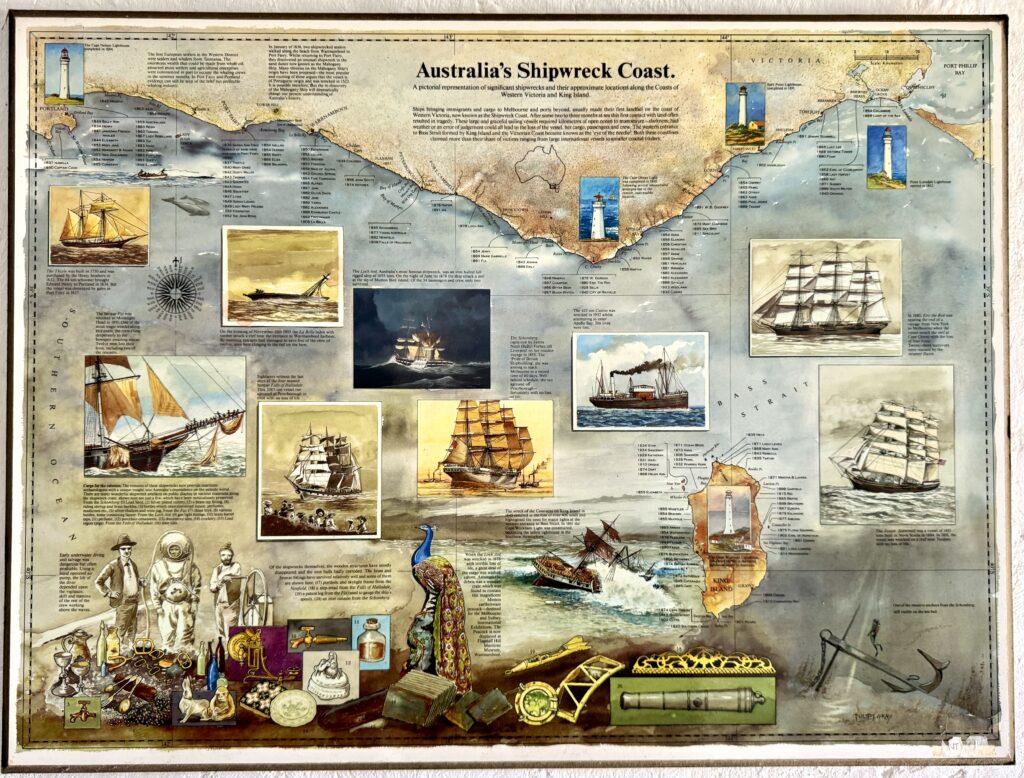

The desperate need for a lighthouse at Cape Otway emerged from an escalating catalogue of maritime catastrophes that starkly exposed the deadly hazards lurking beneath Bass Strait’s deceptively beautiful surface. The early tragedy of the Neva in 1835, which foundered on reefs near King Island claiming 224 lives served as a grim herald of the strait’s dangers, but it was the Cataraqui’s catastrophic destruction in 1845, Australia’s worst civilian maritime disaster with over 400 souls lost to the merciless sea that intensified urgent calls for navigational aids along this cursed coast.

As gold rush fever gripped the nation in the 1850s and shipping traffic surged to unprecedented levels, the wrecks multiplied with horrifying regularity: the Sacramento in 1853, dashed to pieces against the razor-sharp reefs of Point Lonsdale; the Marie Gabrielle in 1869, claimed by the treacherous waters near Aireys Inlet; and the magnificent Schomberg in 1855, wrecked off Peterborough where 77 perished in a foundering that shocked the colonial world. Even after the lighthouse began its watch tragedies continued to unfold with heartbreaking regularity; the Loch Ard in 1878, torn apart on nearby Mutton Bird Island leaving only two survivors of the 54 on board; the Eric the Red in 1880, a proud three-masted barque from New York that struck Otway Reef with another 22 lost lives prompting the installation of additional warning lights and the Fiji in 1891, grounding on the ominous Moonlight Head with 13 drowned in the raging surf.

Countless smaller vessels vanished without trace, their splintered remains washing ashore as mute testimony to the coast’s insatiable appetite for ships and souls. Survivors who lived to tell their tales, experienced pilots who knew these waters intimately, and desperate shipping interests all lobbied colonial authorities to light this passage of darkness or the golden route to Melbourne would remain forever a highway to hell.

Approval for the construction of the lighthouse was finally granted in 1843 but construction didn’t begin until 1846 due to the difficulties encountered in site selection, planning and logistics.

The construction site posed logistical nightmares that would daunt modern engineers; precious sandstone was painstakingly quarried at Parker River, five km to the east, then hauled by teams of bullocks along rough bush tracks that turned to quagmires with every rainfall. Seventy dedicated workers laboured for ten long months in conditions of extreme hardship, carefully fitting each stone block with such precision that not a single drop of mortar was required between the courses.

The magnificent lantern assembly, manufactured by skilled craftsmen in distant Birmingham, arrived after a perilous sea voyage and was landed through thunderous surf using small boats that risked destruction with each wave. Supplies reached the isolated site sporadically and unpredictably, dependent entirely upon favourable weather and sea conditions for delivery. The crushing isolation plagued every aspect of construction; access roads were little more than rough tracks through virgin bush, fresh water sources were limited and unreliable, and the weather could turn savage without warning, halting work for days at a time. Strange whispers began to circulate among the workers, tools mysteriously vanishing in the impenetrable bush during the night, eerie cries echoing from the cliff faces during violent storms, unexplained phenomena that some attributed to the wind’s trickery while others wondered if they were omens of future tragedies.

Cape Otway Lighthouse was first lit on August 29, 1848, its revolutionary catoptric system employing 21 precisely positioned parabolic reflectors to amplify the flames of whale oil into a brilliant beam visible for miles across the treacherous waters.

The lighthouse keepers and their families endured an isolation so complete and profound that it challenged the very limits of human endurance. Essential supplies were landed at the distant Parker River jetty only every six to twelve months, weather permitting, while meaningful contact with the outside world remained limited to rare visitors until improved road access finally arrived in the 1930s. The position’s first keeper was summarily dismissed after just three months for tampering with the crucial light mechanism, replaced by the stalwart Henry Bayles Ford, who dedicated thirty years of his life to maintaining the beacon, his son George later achieving local fame by riding through dangerous terrain to summon help for the Loch Ard survivors.

The detailed logbooks maintained by successive keepers chronicled not merely the steady march of technological progress; the installation of the revolving lens system in 1891, the revolutionary incandescent mantle in 1905, the arrival of electric power in 1939 and connection to mains electricity in 1962 but the deeply human drama of life at the edge of civilisation: daring rescues performed in mountainous seas, violent storms that shook the tower to its foundations, and the psychological toll of unrelenting solitude. Keeper families cultivated vegetable gardens in the thin coastal soil, tended livestock that provided essential fresh meat and milk, and maintained the numerous buildings that comprised their isolated community, yet illness and accidents claimed precious lives with heartbreaking regularity, with bodies sometimes stored in the workshop buildings during winter months when burial was impossible.

The lighthouse’s extreme remoteness and proximity to countless maritime tragedies fostered an atmosphere ripe for supernatural encounters, cementing Cape Otway’s enduring reputation as Australia’s most haunted lighthouse.

Generation after generation of keepers reported unexplained phenomena that defied rational explanation: the sound of heavy footsteps ascending the spiral staircase during the dead of night when all living occupants were accounted for, oil-burning lanterns mysteriously rekindled by invisible hands after being extinguished, and whispered conversations echoing through empty rooms that seemed to relay distress calls from ships long since claimed by the depths. The ghostly apparitions reported over the decades include the restless spirits of shipwreck victims whose broken bodies were once laid out on the lighthouse grounds awaiting burial, tragic women who perished from the crushing isolation and despair of lighthouse life, and a spectral keeper in period uniform who continues his eternal patrol of the tower, ensuring the light never fails those still struggling in the darkness below. The workshop buildings, which served as makeshift morgues during maritime disasters, harbor bone-chilling cold spots and shadowy figures that move just beyond the edge of vision, while the historic telegraph station constructed in 1859 allegedly transmits phantom Morse code messages during violent storms, as if eternally relaying desperate pleas for assistance from vessels already claimed by the deep. Local children spoke in hushed tones of their mysterious “sea friends” who shared tales of long-forgotten wrecks and warned of approaching weather changes, while during howling gales, the very air seemed to fill with the anguished cries of drowned souls seeking the shelter of the light that might have saved them. Modern ghost tours investigate these persistent phenomena with scientific equipment, often capturing electronic voice phenomena featuring desperate voices pleading “help” or naming specific vessels like the ill-fated Loch Ard. One particularly haunting legend tells of Captain Angus, a ghostly mariner condemned to eternal vigil, forever watching the horizon for his lost ship while the sweet scent of his pipe tobacco drifts through the keeper quarters on still nights.

As maritime technology advanced into the modern era, Cape Otway Lighthouse was finally decommissioned in 1994 after an extraordinary 146 years of faithful service, its original Fresnel lens extinguished in a poignant ceremony attended by thousands who came to honour its legacy, with operational duties transferred to a practical solar-powered beacon mounted on a modest 2m structure nearby. Yet even today maintenance crews continue to report ongoing anomalies that suggest the lighthouse’s supernatural reputation remains well-deserved: electronic equipment activating without human intervention, radio systems crackling with archaic signal patterns that match no modern transmission protocols, and mysterious figures dressed in period clothing waving from the tower’s external balcony before vanishing into the coastal mists. Local commercial fishermen, whose families have worked these waters for generations, studiously avoid the cape on the anniversaries of major wrecks, claiming to witness strange underwater lights that trace the ghostly outlines of phantom hulls along the seabed, while experienced divers exploring the numerous wreck sites report encountering eerie zones of absolute silence where even the constant background noise of the sea mysteriously ceases.

Today, the lighthouse stands not merely as a beacon casting light across treacherous waters, but as a powerful monument in remembrance for the countless souls claimed by Bass Strait’s unforgiving embrace, serving as an eternal reminder to all visitors that some forces of nature and perhaps the supernatural, remain forever wild and untamed.

Technical Specifications

First Exhibited: August 29, 1848

Status: Decommissioned (1994); replaced by automated light

Location: Cape Otway, Great Ocean Road, Victoria, Australia (Latitude 38° 51’ south, Longitude 143° 29’ east)

Construction: 1846-1848, sandstone tower

Tower Height: 21 metres

Focal Elevation: 91 metres above sea level

Original Optic: Catoptric system with 21 parabolic reflectors

Range: Nominal: White 19 nautical miles, Red 15 nautical miles; Geographical: 21 nautical miles

Character: Fl (3) W 30s (three white flashes every 30 seconds) with red sector

Current Power Source: Solar panels (automated light)

Current Operator: Australian Maritime Safety Authority