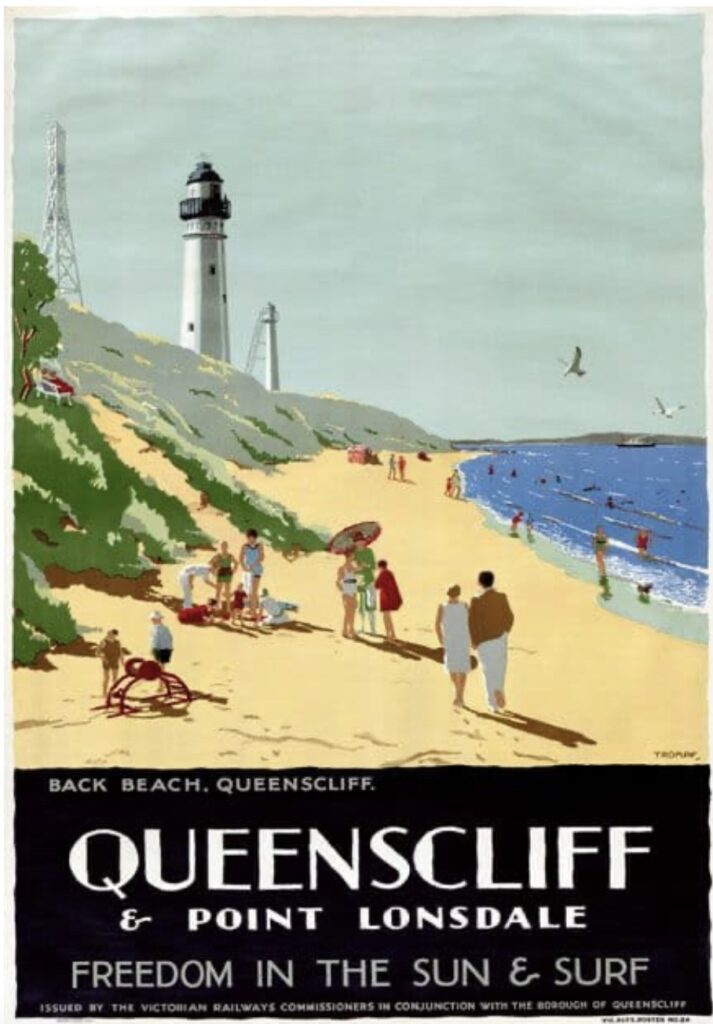

The Queenscliff Lighthouses stand on the eastern edge of the Bellarine Peninsula in Victoria, guiding mariners through the narrow and treacherous passage known as “The Rip” at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay. Comprising the distinctive Black Lighthouse (High Light) and White Lighthouse (Low Light), these structures form a crucial navigational aid that has guided vessels through one of the world’s most dangerous waterways for over 160 years.

Perched on Shortland Bluff, the lighthouses overlook the swirling currents where Bass Strait meets the powerful tidal flows of Port Phillip Bay. The Rip is a dramatic chokepoint, a mere 3 kms wide at its narrowest—where tidal flows reach speeds of up to 6 knots, creating standing waves and eddies that challenge even the most experienced mariners. Port Phillip Bay has served as Melbourne’s gateway since the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s and 1860s, attracting vessels from across the globe. Yet this attraction came at a deadly cost, as low-lying headlands and hidden dangers ensnared unwary ships in conditions that could shift from serene to savage in moments.

The indigenous Boonwurrung people, traditional custodians of the lands around Port Phillip Bay, long revered this area as a place of spiritual power and peril. Their oral traditions spoke of the bay as Bunjil’s domain, where the creator spirit watched over the waters and warned of invisible forces that could drag vessels to their doom. European settlers, arriving in the early 19th century, soon learned the truth of these warnings as shipwrecks piled up along the shores as grim reminders of the sea’s unforgiving nature.

The pressing need for reliable navigational aids became evident following devastating maritime disasters that exposed The Rip’s lethal hazards. The wreck of the Isabella Watson on March 21, 1852, was among the most harrowing early disasters. This immigrant ship, carrying gold rush seekers to Melbourne, struck a reef in heavy seas while attempting to navigate the entrance during a gale. The vessel broke apart rapidly, claiming 10 lives, with survivors clinging to wreckage until rescued by local pilots. The tragedy highlighted the absence of adequate lighting and signalling, as captains relied on crude landmarks and luck to thread the needle through the Heads.

Other significant losses included the William Salthouse (1841), which struck Pope’s Eye Shoal; the Frisk (1853), dashed against rocks in poor visibility; the Sea that same year, overwhelmed by tides; and the Non Pareil (1857), which foundered outbound with cargo lost to the depths. These incidents, often exacerbated by fog, inaccurate charts, and the bay’s deceptive calm masking underwater perils, spurred colonial authorities to action. Later disasters reinforced the urgency. The Hurricane (1869) misjudged the channel in strong currents, while the pilot schooner Rip itself was overwhelmed by an enormous wave in 1873, killing four crew members. Perhaps most infamous was the Cheviot in 1887, a steamship that struck Point Nepean Reef while exiting The Rip, breaking in two and drowning 35 people in a catastrophe that shocked the nation. This tragedy was compounded in 1967 when Prime Minister Harold Holt was lost at sea whilst swimming at Cheviot beach, named in memory of this disaster.

Construction began in the early 1860s, with the High Light (Black Lighthouse) erected in 1862 and the Low Light (White Lighthouse) following in 1863. Colonial engineers faced formidable logistical hurdles at this exposed coastal outpost. Materials, including bluestone quarried in Melbourne or possibly shipped as ballast from Scotland, had to be transported by sea to the bluff, braving the very dangers the lighthouses aimed to mitigate. Workers contended with howling winds, eroding cliffs, and supply shortages, as fresh water and provisions were scarce on the peninsula. The High Light’s design was curiously adapted from a wave-washed Scottish model with curved walls and an elevated entrance accessed by rope ladder. Though its placement 40 meters above sea level rendered such features redundant, this spoke to the engineers’ caution.

Strange incidents during construction fuelled local whispers. Tools vanished overnight, only to reappear in odd arrangements, and workers reported eerie sounds echoing from the bay—perhaps the cries of past victims carried on the wind. Though not as documented as other sites, these occurrences hinted at the site’s charged atmosphere, where the boundary between the living and the lost seemed blurred. The lighthouses were completed amid the gold rush frenzy, with Fort Queenscliff later enveloping the High Light as defences against potential privateer attacks on gold shipments.

The lighthouses first illuminated paired beams providing a leading line through The Rip, with vessels aligning the High Light above the Low Light to stay in the safe channel. Keepers maintained the lamps, initially oil-fuelled, then gas from 1890, and electricity by 1924. Logbooks recorded not just routine operations but dramatic rescues, as keepers signalled to distressed ships amid storms. While the lighthouses saved countless lives, tragedies persisted: the SS Glenelg vanished in 1900 with 38 aboard, presumed lost in The Rip; the Petriana tanker wrecked in 1903, causing Australia’s first major oil spill; and the SS Time grounded on Corsair Rock in 1949, its salvage becoming a local spectacle.

The isolation bred an aura of mystery. While not overtly haunted like many others, Queenscliff’s maritime heritage includes strange tales with keepers occasionally reporting unexplained lights bobbing in The Rip during fog, as if phantom vessels replayed their final voyages. The town itself harbors legends: the ghost of Johnny Hulston’s unsolved murder in 1893 is said to wander near the Heads, his restless spirit calling out in the night. At nearby establishments like the Royal Hotel, apparitions of two drowned sisters from the 19th century appear in basements, their laughter echoing as a haunting reminder of their tragic loss. Families at the lighthouses developed superstitions, leaving lanterns burning for “visitors from the deep” and heeding children’s uncanny predictions of approaching gales.

During World War II, the High Light’s position in Fort Queenscliff added layers of tension, with reports of shadowy figures in outdated uniforms patrolling the bluff—perhaps echoes of soldiers or lost sailors. When automation arrived in 1999, the human presence faded, but the lighthouses’ vigil endures. Maintenance teams now arrive by road or boat, occasionally noting equipment anomalies: lights flickering in Morse-like patterns or radios crackling with faint, archaic distress calls. Local divers exploring the wrecks below report underwater illuminations tracing ghostly hulls, while fishermen avoid certain anniversary dates, claiming The Rip stirs with unrest.

Today, the Queenscliff Lighthouses remain active under the Port of Melbourne Corporation, their solar powered LED lights guiding modern shipping through a passage tamed but never conquered.

Technical Details

High Light (Black Lighthouse)

- First Exhibited: 1862

- Status: Active (automated)

- Location: Fort Queenscliff, Shortland Bluff, Bellarine Peninsula, Victoria

- Construction: 1862, adapted from Scottish wave-washed design

- Material: Bluestone (quarried in Melbourne or shipped from Scotland)

- Tower Height: Approximately 15 metres

- Focal Elevation: 40 metres above sea level

- Design Features: Curved walls, elevated entrance (originally accessed by rope ladder)

- Colour: Black exterior

- Original Power Source: Oil lamps

- Power Evolution: Oil (1862-1890), Gas (1890-1924), Electric (1924-1999), Solar LED (1999-present)

- Current Operator: Port of Melbourne Corporation

Low Light (White Lighthouse)

- First Exhibited: 1863

- Status: Active (automated)

- Location: Shortland Bluff, Bellarine Peninsula, Victoria

- Construction: 1863

- Material: Bluestone

- Colour: White exterior

- Original Power Source: Oil lamps

- Power Evolution: Oil (1863-1890), Gas (1890-1924), Electric (1924-1999), Solar LED (1999-present)

- Current Operator: Port of Melbourne Corporation