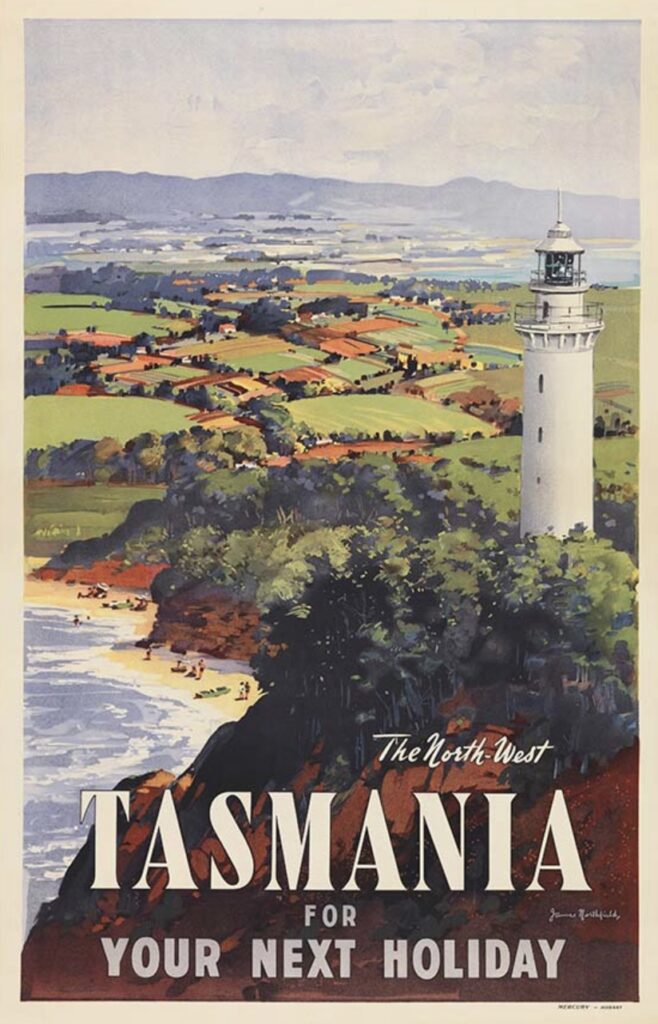

Table Cape Lighthouse stands at the edge of a spectacular circular headland, rising nearly 180 metres above the treacherous waters of Bass Strait. Located just five kilometres from the town of Wynyard on Tasmania’s northwest coast, this lighthouse has guided countless vessels through some of Australia’s most challenging maritime waters for over a century.

The cape’s remarkable geological formation, with its distinctive flat-topped profile, was named by British navigator Matthew Flinders during his circumnavigation of Van Diemen’s Land with George Bass in 1798. Rising from the sea like a natural fortress, Table Cape presents a sheer cliff face to Bass Strait, creating an imposing barrier that has both protected and threatened mariners for centuries. The surrounding waters, where Bass Strait meets the northwest coast of Tasmania, are notorious for their unpredictable conditions, fierce winds, and hidden reefs, making this stretch of coastline a graveyard for ships.

The urgent need for a lighthouse at Table Cape became increasingly apparent as maritime traffic through Bass Strait intensified during the late 19th century. The cape’s strategic position overlooking the shipping lanes between mainland Australia and Tasmania made it a critical navigation point, yet its prominence also made it a deadly hazard for vessels caught in poor weather or struggling with navigation in the pre-GPS era.

Bass Strait was already recognised as one of the world’s most treacherous waterways, claiming over 1,000 vessels and an unknown number of lives lost at sea. The recognition of Van Diemen’s Land as an island followed the wreck of the ship Sydney Cove in Bass Strait in 1797, setting a grim precedent for the maritime disasters that followed.

The rugged, rocky foreshore below Table Cape became the scene of numerous shipwrecks prior to the lighthouse’s construction, with vessels driven against the unforgiving cliffs by powerful winds and currents. Two vessels, in particular, sealed the fate of Table Cape as a lighthouse location, their tragic losses providing the final impetus needed to overcome bureaucratic delays and funding concerns.

The first was the Emma Prescott in 1867, a vessel that foundered on the treacherous coastline below the cape, adding another name to the growing list of ships claimed by these waters. The loss highlighted the particular danger posed by Table Cape’s commanding profile, which could appear suddenly out of storms and fog to catch mariners unprepared.

Even more devastating was the loss of the schooner Orson in 1884, a tragedy that finally spurred authorities into action. The Orson’s wreck demonstrated conclusively that the approaches to Wynyard and the mouth of the Inglis River could no longer remain unlit.

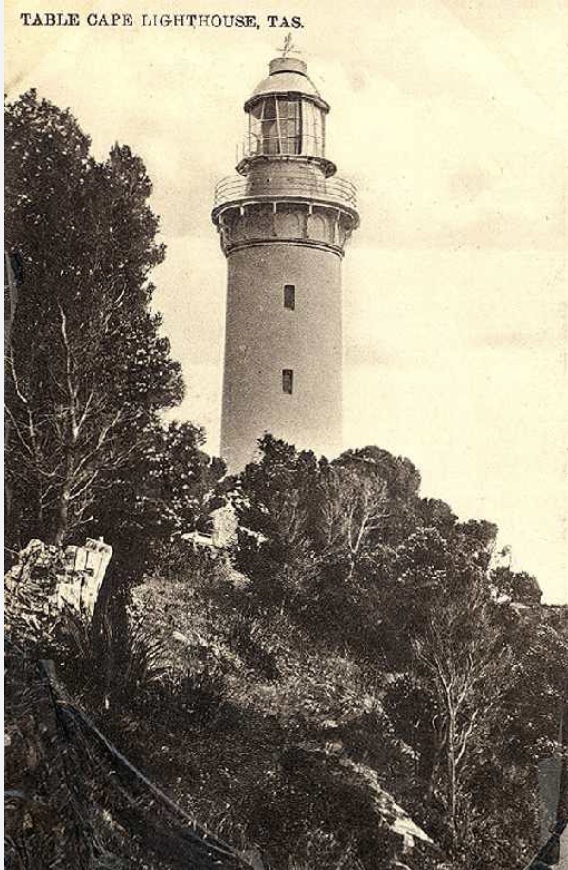

Designed by Huckson & Hutchison, construction began in 1886, with the project awarded to contractor Mr. John Luck. The challenging logistics of building on such a remote and elevated site required both local knowledge and innovative solutions.

The lighthouse was completed and entered service in 1888, initially powered by oil before being converted to automatic acetylene operation in 1920. This technological advancement improved both reliability and efficiency, reducing the manual labour required to maintain the light whilst increasing its consistency.

From its commissioning in 1888 until 1920, Table Cape Lighthouse was a staffed station, home to more than twelve lighthouse keepers and their families over its thirty-two years of manned operation. These dedicated individuals faced the unique challenges of life on an exposed headland, isolated from the broader community yet bearing the enormous responsibility of maintaining a beacon upon which countless lives depended.

The keepers developed strong bonds with each other and with the broader lighthouse-keeping community across Tasmania and beyond. These familial ties transcended local, national, and international borders, creating a network of shared experience and mutual support that connected lighthouse families worldwide. The traditions and knowledge passed down through generations of keepers created a unique culture that valued precision, dedication, and an intimate understanding of the sea’s moods and dangers.

Life on Table Cape was governed by the rhythms of the lighthouse operation and the ever-changing conditions of Bass Strait. Keepers maintained detailed logs of weather observations, shipping movements, and the performance of the lighthouse equipment. Their isolation meant they became skilled in self-sufficiency, maintaining gardens where possible and developing the resourcefulness necessary to handle emergencies without immediate outside assistance.

Beyond the Emma Prescott and Orson disasters that directly prompted the lighthouse’s construction, the broader region witnessed numerous other maritime tragedies that underscored the constant danger faced by vessels navigating these waters. Over the years, there have been mysterious disappearances where ships and their entire crews vanished without a trace. These include the cutter Glimpse, en route from Wynyard to Launceston, resulting in the loss of all hands, demonstrating that even local vessels familiar with these waters were not immune to the area’s dangers. Other ships that disappeared without a trace include the schooners Red Jacket and Reindeer and the brigs Creole and Grecian Queen, all with no survivors. The complete disappearance of these vessels created an atmosphere of supernatural dread amongst mariners, who began to speak in hushed tones of ships that simply vanished, leaving no survivors to tell their tales.

Local Aboriginal peoples had long recognised the spiritual significance of these waters, understanding that certain areas of the coast were places where the boundary between the world of the living and the realm of the ancestors became thin. European settlers, whilst dismissing such beliefs as superstition, nonetheless found themselves unable to explain the strange phenomena that seemed to cluster around areas of repeated maritime disaster.

As the lighthouse began operations in 1888, stories began to circulate amongst the local population about unexplained phenomena associated with the cape and its surrounding waters. Fishermen reported seeing lights moving beneath the surface of the sea on calm nights, lights that seemed to follow the paths of vessels long since lost to the depths. These underwater illuminations, described as pale and ethereal, would appear most commonly during the anniversary dates of major shipwrecks, as if the lost souls were attempting to signal their presence to the world above.

The lighthouse keepers, isolated on their windswept promontory, became unwilling witnesses to events that defied rational explanation. Several keepers reported seeing phantom ships struggling through phantom storms, their crews fighting desperately against waves that existed only in some otherworldly dimension. These spectral vessels would appear most commonly during severe weather, as if the cape’s elevation allowed the keepers to peer through the veil between worlds and witness the eternal replay of maritime disasters.

One keeper, whose name was lost to history but whose account was preserved in local folklore, claimed to have seen the Emma Prescott fighting her final battle against the rocks below the cape. According to his testimony, recorded by a visiting clergyman in 1891, the phantom vessel would appear at precisely the same time each year, her crew visible on deck as they struggled to save their ship from the inevitable. The keeper described watching helplessly as the ghostly drama played out, knowing that he was witnessing a tragedy that had occurred decades earlier yet seemed as real and immediate as if it were happening for the first time.

Throughout the staffed period of the lighthouse’s operation, keepers reported a puzzling phenomenon that seemed to have no rational explanation. Supplies delivered to the station would occasionally disappear overnight, only to be discovered days or weeks later in locations where they could not possibly have been placed by human hands. Food stores would be found arranged on the rocks below the cape, as if someone had carefully laid out provisions for invisible guests. Tools would vanish from locked storage rooms, only to reappear in the lighthouse lantern room, positioned with mathematical precision around the great lens.

The keepers began to theorise that the spirits of those lost in the surrounding waters were somehow attempting to communicate with the living, using the lighthouse as a focal point for their otherworldly presence. Some families reported that their children would speak of “sea friends” who visited them in their dreams, describing in detail the faces and clothing of people they had never seen but who matched descriptions of those lost in historical shipwrecks.

Most unsettling was the recurring discovery of personal items that had no connection to any current or former lighthouse inhabitants. A pocket watch bearing the initials “E.P.” was found in the lighthouse kitchen in 1892, leading local historians to speculate about a connection to the Emma Prescott disaster. A child’s leather boot, worn smooth by seawater, would appear periodically in different locations around the station, despite the keepers’ attempts to dispose of it. Each time they threw it into the sea, it would return within days, placed carefully on the lighthouse steps as if someone was determined that it not be forgotten.

The automation of Table Cape Lighthouse reflected broader changes in maritime navigation and lighthouse technology. As shipping became more sophisticated and alternative navigation aids became available, the role of traditional lighthouses evolved. However, Table Cape’s strategic position and the continuing challenges of Bass Strait navigation ensured its continued importance as a maritime safety aid.

The lighthouse’s conversion to automatic operation in 1920 was pioneering for its time, demonstrating the reliability of acetylene systems and paving the way for similar conversions at other remote lighthouse stations. This technological advancement allowed lighthouse authorities to maintain navigation aids in locations where the cost and difficulty of staffing had previously made operation challenging.

Today, Table Cape Lighthouse continues to serve as both a vital navigation aid and a popular tourist destination. The lighthouse and its spectacular setting attract visitors who come to appreciate both the engineering achievement it represents and the breathtaking views it offers across Bass Strait. The surrounding area, now known for its scenic farmlands and seasonal tulip farms, provides a striking contrast to the industrial purpose for which the lighthouse was originally constructed.

Technical Details:

- First Exhibited: 1888

- Status: Active (Automated)

- Architects: Huckson & Hutchison

- Contractor: Mr. John Luck

- Location: Table Cape, Lat: 40°57’ S, Long: 145°44’ E

- Tower Height: 25 metres

- Focal Elevation: 190 metres above sea level

- Automation: 1920

- Original Lens: Chance Bros. 2nd Order

- Range: 16 nautical miles (red), 19 nautical miles (white)

- Character: Fl. WR (2) 10 sec.

There are several other lesser lights along Tasmania’s north coast including Highfield Point at Stanley, Rocky Cape near Boat Harbour and Round Hill outside Burnie. I visited these lights but don’t think they are interesting enough for their own stories, however, for the record I have included photos of each below.