Positioned on Tasmania’s remote northeastern coast, Eddystone Point Lighthouse stands as a magnificent granite monument to seafarers guarding the treacherous waters where Bass Strait meets the Tasman Sea. This imposing lighthouse has played a critical role in safeguarding mariners who have long considered this area to be one of the most hazardous stretches of Tasmania’s coastline, notorious for its hidden reefs, unpredictable currents, and frequently challenging weather conditions.

Eddystone Point Lighthouse forms a crucial link in Tasmania’s eastern chain of coastal lights, working in conjunction with Deal Island Lighthouse to the north and Cape Tourville Lighthouse to the south to provide comprehensive navigational coverage along Tasmania’s eastern seaboard, a vital shipping corridor for vessels traveling between Australia’s southern ports and the Pacific.

The lighthouse presides over what was historically one of Tasmania’s most treacherous maritime regions, where vessels rounding the island’s northeastern corner faced the dangerous transition from the relatively sheltered waters of Tasmania’s east coast to the fully exposed conditions of Bass Strait and the Tasman Sea. This critical position marks a pivotal navigation point for shipping, with the lighthouse serving as both warning beacon and reassuring guide to vessels traversing this challenging nautical junction.

The lighthouse was commissioned in 1889 in response to numerous maritime disasters along Tasmania’s northeastern coast. The urgent need for the government to take action had been highlighted by multiple shipwrecks, with the loss of several vessels and numerous lives in the preceding decades compelling colonial maritime authorities to establish a major light station despite the area’s remote and challenging location.

Designed by Tasmanian Colonial Architect Robert Huckson, Eddystone Point Lighthouse exemplifies the monumental solidity of late Victorian lighthouse architecture at its most impressive. The magnificent tower rises 35m from base to lantern, with a focal plane 42m above sea level. This commanding height enables the light to be visible for approximately 26 nautical miles, providing a crucial early warning to vessels approaching Tasmania’s eastern coastline.

The lighthouse’s construction represents one of the most remarkable engineering achievements in Tasmania’s colonial history. Built entirely from locally quarried pink granite blocks, the tower features a classical tapered design with walls nearly 3 meters thick at the base, gradually tapering as it rises. The precision of the stonework is extraordinary, with each massive granite block expertly shaped and fitted to create a structure of exceptional beauty and strength. This masterpiece of masonry has withstood more than 135 years of the Tasman Sea’s fiercest storms with minimal deterioration, testament to the extraordinary quality of both materials and workmanship.

One of Eddystone Point’s most impressive features is its internal structure, particularly its magnificent spiral staircase. The 120 granite steps wind elegantly around a central column from base to lantern room, each step a single piece of expertly carved granite. This remarkable feat of stone craftsmanship represents some of the finest heritage stonework in Australia, creating a stairway of exceptional durability and architectural beauty that has required minimal restoration throughout the lighthouse’s long operational history.

When first commissioned, the lighthouse was equipped with state-of-the-art illumination technology in the form of a first-order Chance Brothers dioptric apparatus. This precision optical system, manufactured by the world’s preeminent lighthouse engineers, utilized a five-wick kerosene lamp as its light source, producing a powerful fixed white light that revolutionized navigation safety in the region. The complex lens arrangement concentrated and projected the light with remarkable efficiency, creating a beam visible far beyond the horizon.

Throughout its operational history, the lighthouse underwent several significant technological transitions. The original kerosene illumination was upgraded to pressurized kerosene vapor in 1913, substantially increasing the light’s intensity. Electrification came in 1959, dramatically improving reliability and further enhancing brightness. Despite these modernizations, the lighthouse retained its original Chance Brothers lens assembly, which was carefully preserved and maintained throughout these transitions, a practice that continues to this day.

Life for keepers at Eddystone Point represented the quintessential lighthouse experience, combining extraordinary natural beauty with profound isolation. The light station complex included substantial granite keeper’s quarters for three families, a series of outbuildings, and eventually a school and post office, establishing a largely self-sufficient community at this remote outpost. The nearest settlement was St. Helens, some 35 kilometers away by rough track, meaning that for much of its history, the lighthouse community relied heavily on quarterly supply vessels and their own resourcefulness.

The station’s extreme isolation subjected both the lighthouse and its keepers to considerable environmental challenges. Eddystone’s exposed position makes it particularly vulnerable to the powerful easterly gales that sweep in from the Tasman Sea, with historical records documenting numerous storms where winds exceeding 120 kph battered the station, driving seas that occasionally broke over the lower sections of the lighthouse grounds despite their elevated position.

Historical keeper logs detail extraordinary weather events, with entries describing “continuous horizontal rain making visibility between buildings near impossible” and “seas breaking over the assistant keeper’s roof, the spray reaching the tower base.” During particularly severe weather, keepers would maintain continuous watch, ensuring the light remained operational through conditions that would occasionally prevent supply vessels from reaching the station for months at a time.

The waters surrounding Eddystone Point have claimed numerous vessels throughout history, highlighting the vital importance of the lighthouse’s warning beam. Notable incidents include the tragic wreck of the steamship Standard in 1894, which struck submerged rocks despite the lighthouse being operational, and the dramatic loss of the Coliban in 1907, driven ashore during an exceptional gale. Even with the light’s guidance, the combination of treacherous reefs, powerful currents, and sometimes ferocious weather conditions meant the waters around Eddystone remained challenging for mariners throughout much of its history and to the current day.

Like many remote lighthouse stations, Eddystone Point accumulated its share of folklore and legends. The most enduring involves the so-called “Weeping Light,” a phenomenon first recorded in keeper logs during the 1920s, wherein under specific atmospheric conditions, the lighthouse beam appeared to split and create a secondary, downward-pointing beam that local Aboriginal communities interpreted as the lighthouse “crying” for those lost at sea. While meteorologists later explained this rare optical effect as resulting from unusual atmospheric refraction, the story became embedded in local maritime tradition.

Among the station’s most remarkable documented incidents was the “Great Storm of 1917,” when Head Keeper William McDougall and his assistants maintained the light continuously for three days while hurricane-force winds devastated the surrounding landscape, tore the roof from one outbuilding, and drove seawater across the station grounds with such force that salt deposits reportedly coated the tower windows 30 meters above ground level. This extraordinary demonstration of keeper dedication became part of Australian lighthouse folklore and was later commemorated in a series of paintings by Tasmanian maritime artist Walter Beauchamp.

The lighthouse gained additional historical significance during World War II when it served as an important coastal observation post, with keepers maintaining constant watch for enemy vessels or suspicious activity in the Tasman Sea. Several Japanese submarine sightings were reported from Eddystone during this period, highlighting the lighthouse’s strategic importance beyond its traditional navigational role.

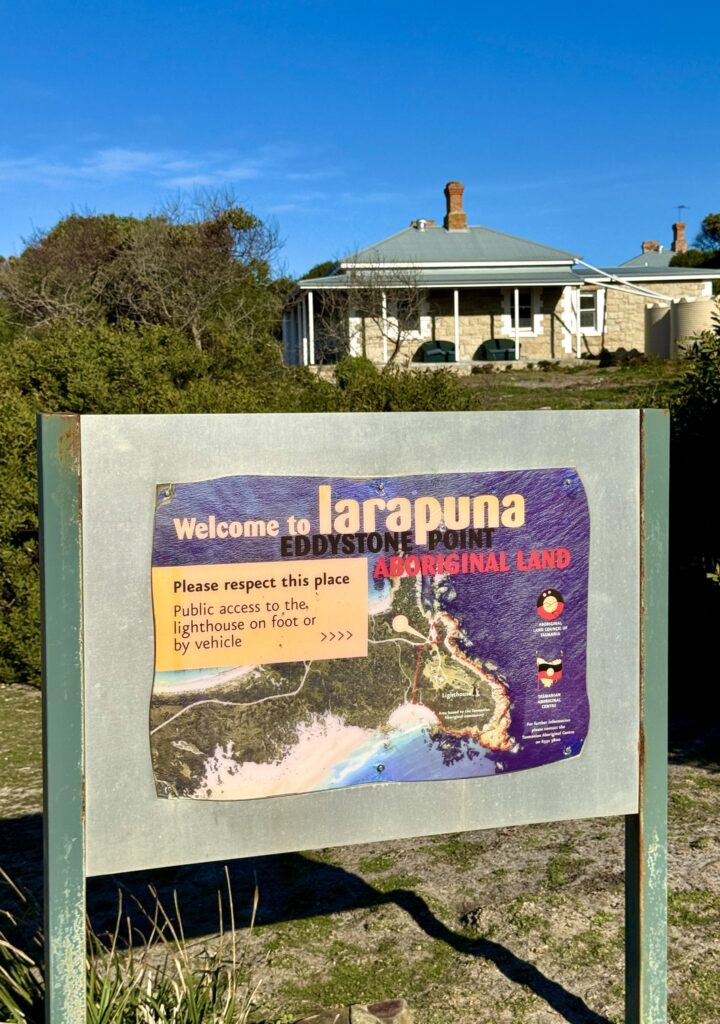

Though automated in 1973, ending 84 years of continuous keeper presence, Eddystone Point has been exceptionally well preserved as one of Tasmania’s most significant maritime heritage sites. The lighthouse precinct is now managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, with the magnificent granite tower and keeper’s quarters standing as an extraordinary monument to Tasmania’s maritime history. The station’s location within the Mount William National Park has ensured its natural setting remains largely unchanged, allowing visitors to experience the lighthouse much as it would have appeared to generations of keepers and their families.

Today, Eddystone Point Lighthouse continues to function as an active navigational aid under the management of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, while also serving as one of Tasmania’s premier heritage tourism destinations. The keeper’s quarters now house interpretive displays documenting the station’s rich history and the lives of those who maintained this remote outpost. Guided tours allow visitors to climb the magnificent granite staircase to the lantern room and witness the original Chance Brothers lens that has guided mariners safely for more than a century.

Having withstood more than 135 years of the Tasman Sea’s most powerful storms, witnessed the evolution of maritime traffic from colonial sailing ships to modern vessels, and transitioned from kerosene lamps to automated systems, Eddystone Point Lighthouse stands as an enduring monument to Australia’s maritime heritage. Its magnificent pink granite tower, gleaming against the dramatic coastal landscape, continues to be one of Australia’s most architecturally significant lighthouses and a powerful symbol of the human dedication that maintained these isolated beacons through decades of storms, solitude, and unwavering commitment to mariner safety.

p.s. This lighthouse is not to be confused with it’s more famous but much less attractive namesake Eddystone Rock lighthouse, which sits off Rame Head, in Cornwall south west England, or the most outrageous surf break in the world, Eddystone Rock, off the southern tip of Tasmania.

Technical Details:

First Exhibited: 1889

Architect: Robert Huckson

Status: Active

Location Lat: 40° 59.5834′ S Long: 148° 20.9167′ E

Current Optic: Chance Brothers lens relocated from Cape Du Couedic (SA) in 1961

Automated & demanned: 1973

Construction Pink granite tower and lantern with copper dome

Height 35 m

Elevation 42 m

Range Nominal: 22 nml Geographical: 26 nml

Character: Flashing white light: every 10 seconds

Intensity: 540,000 cd