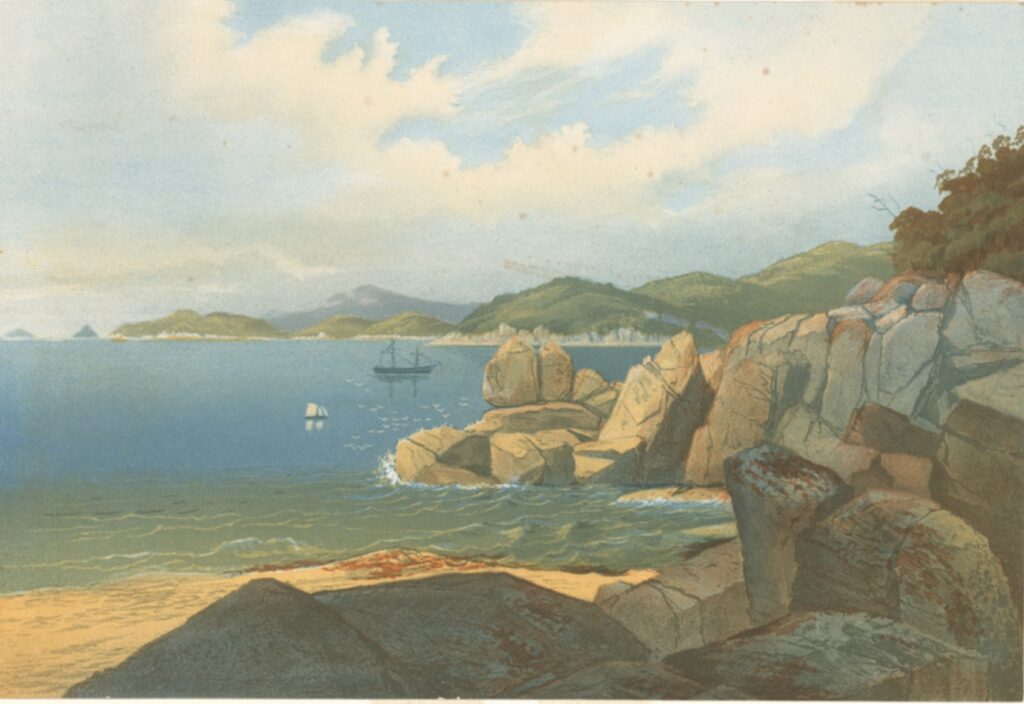

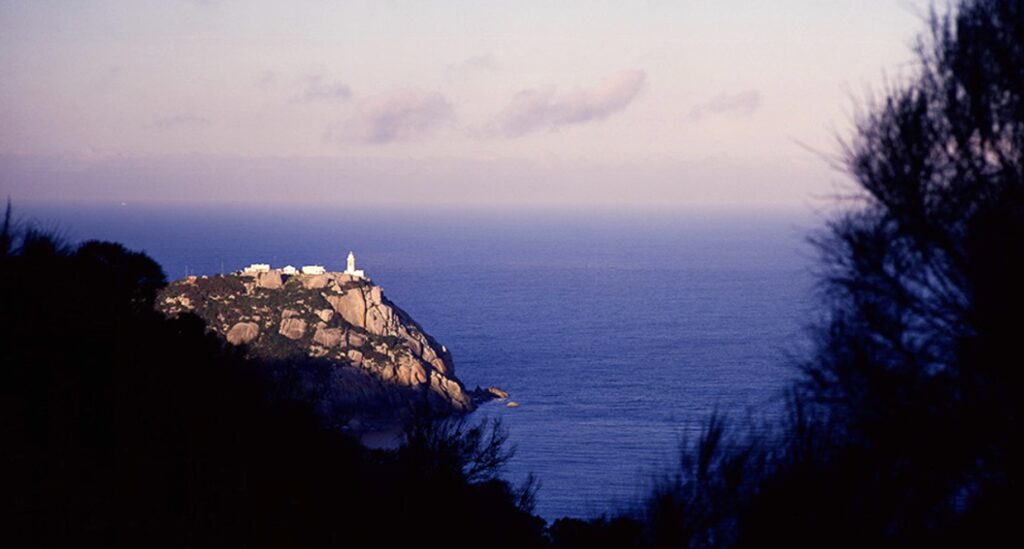

Perched atop a massive granite outcrop on the southernmost point of mainland Australia, Wilsons Promontory Lighthouse stands watch over the treacherous waters at the eastern end of Bass Strait. For over 160 years, its powerful beam has guided countless vessels through one of Australia’s most hazardous maritime passages.

The lighthouse occupies a commanding position on Southeast Point, the southern extremity of Wilsons Promontory National Park in Victoria. This location was chosen to mark the critical junction where ships must negotiate the dangerous waters between mainland Australia and Tasmania, an area notorious for it’s unpredictable and often violent weather and sea conditions.

Like most lighthouses of its era the location of this lighthouse was prompted by the alarming frequency of shipwrecks in the surrounding waters during the early colonial period. As maritime traffic increased following the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s, the need for a lighthouse became increasingly urgent. The loss of several valuable cargo ships in the vicinity, including the ill-fated Clonmel in 1841, underscored the deadly nature of the unforgiving coastline and provided the impetus for the lighthouses construction. One can’t help but think the loss of gold was more of a concern to the authorities than the loss of life!

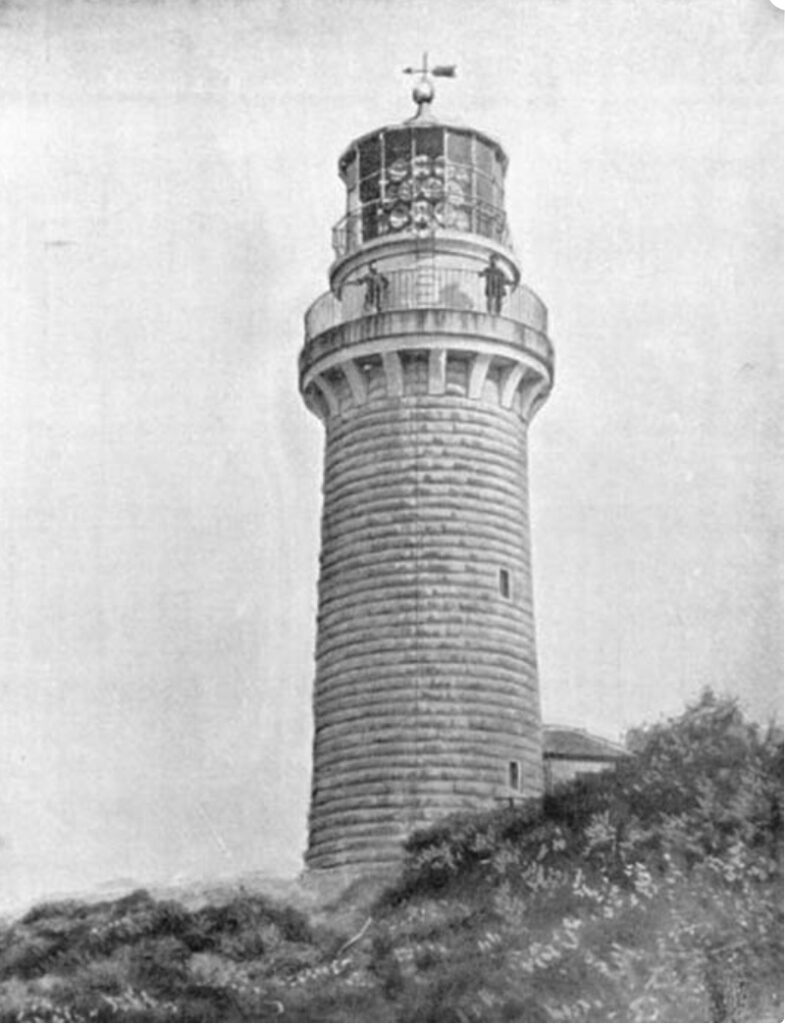

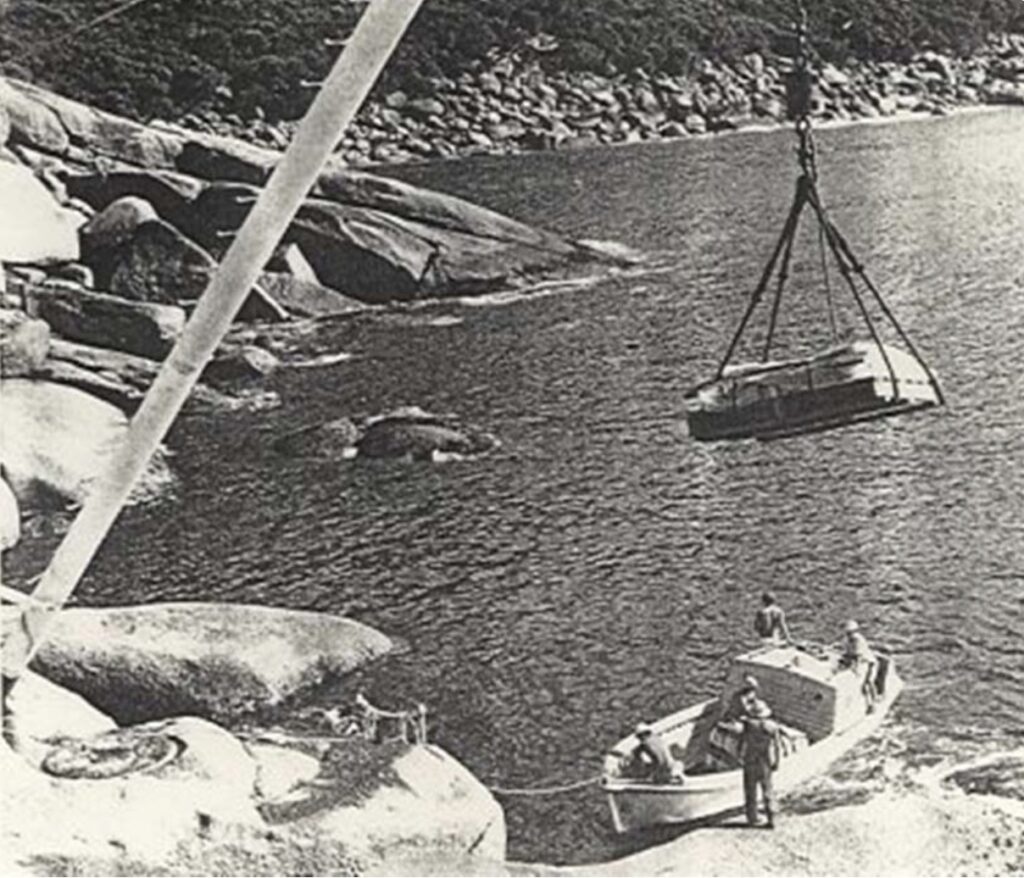

Designed by the Victorian Colonial Architect Charles Maplestone, Wilsons Promontory Lighthouse embodies the quintessential colonial lighthouse architectural tradition. Construction began in 1853 under extraordinarily challenging conditions, with all materials required for building having to be transported by sea to this remote location. The difficult terrain necessitated the creation of a temporary tramway to move granite, timber, and other supplies from the landing beachg up the steep slopes to the construction site.

The lighthouse rises 19m from its base to the lantern room, with the focal plane of the light sitting an impressive 117m above sea level due to the height of the promontory itself. This elevation enables the light to be visible for approximately 26 nautical miles in clear conditions, making it one of the most powerful lighthouses on the Australian coast. The tower’s classic cylindrical design, constructed from locally quarried granite blocks, provides exceptional durability against the extreme weather conditions frequently experienced at this exposed location. The structure features walls nearly two meters thick at the base, tapering gradually as the tower rises. This robust construction has allowed the lighthouse to withstand hurricane-force winds and powerful storms that regularly batter the promontory.

When first commissioned in 1859, the lighthouse was equipped with a first-order catadioptric apparatus manufactured by Chance Brothers of Birmingham, then the world’s leading lighthouse equipment supplier. This powerful beacon immediately proved its value, significantly reducing shipping incidents in this previously perilous stretch of coastline.

Throughout its operational history, the lighthouse underwent several technological upgrades. In 1975, the lighthouse was electrified, dramatically increasing its effectiveness and reducing the intensive maintenance requirements of earlier illumination systems. Finally, in 1993, the lighthouse was fully automated, ending over 130 years of continuous human presence at the station.

Life for the keepers at Wilsons Promontory represented perhaps the most extreme example of isolation in the Australian lighthouse service. Located approximately 30km from the nearest settlement at Tidal River, and with no road access, the lighthouse station functioned as an entirely self-sufficient community. Supplies arrived quarterly by sea, weather permitting, and keepers developed remarkable resourcefulness to sustain their families between these infrequent deliveries.

The station included substantial accommodations designed to house three lighthouse keepers and their families. The impressive keepers’ quarters, constructed from the same local granite as the tower itself, featured separate wings for each family while sharing certain communal facilities. This architectural arrangement fostered a close-knit community while respecting the hierarchical structure of the lighthouse service, with the principal keeper occupying the most spacious quarters.

The isolation experienced by residents extended beyond mere physical distance. Before the introduction of radio communication in the 1930s, keepers might go months without contact with the outside world beyond the occasional supply vessel. This isolation was particularly challenging during medical emergencies, with numerous entries in the station logs documenting desperate measures taken to treat serious injuries or illnesses without access to professional medical care.

The environmental conditions at Wilsons Promontory subjected both the lighthouse and its keepers to extraordinary challenges. Situated at the convergence point of several major weather systems, the promontory experiences some of Australia’s most extreme meteorological events. Records from the lighthouse’s weather station document sustained winds exceeding 165 kph, with gusts approaching 200 kph during the most severe storms.

During particularly violent weather, the keepers maintained continuous watch, ensuring the light remained operational through conditions that could send massive waves crashing against cliffs. The station logs contain numerous accounts of nights where the entire promontory seemed to tremble under the assault of these tempests, with spray from breaking waves reaching the lighthouse windows, almost 120m above sea level!

The waters surrounding Wilsons Promontory have claimed many vessels throughout history, earning the area a sinister reputation among mariners long before European settlement. Indigenous Australian oral traditions contain numerous references to the dangerous waters of the promontory, suggesting the areas treacherous nature has been recognised for thousands of years.

Colonial maritime records document dozens of significant shipwrecks in the vicinity, with the SS Clonmel disaster of 1841 perhaps the most notable. This early steam passenger vessel struck a sandbar near the promontory with 80 people aboard. Though all passengers survived the initial grounding, the difficult rescue operation underscored the need for improved navigational aids in the region.

Even after the lighthouse began operation, the extreme conditions occasionally overwhelmed vessels in distress. The lighthouse keepers frequently found themselves serving as first responders to maritime emergencies, organising rescue efforts and providing initial care to survivors. The keepers’ logs record numerous heroic rescues where staff risked their own lives to save others, descending treacherous cliffs or launching small boats into turbulent seas to reach survivors.

Like many isolated lighthouses with histories of shipwrecks and hardship, Wilsons Promontory has accumulated a rich folklore of supernatural occurrences. The most persistent stories involve reports of a “lady in blue” believed by many to be connected to the tragic drowning of a keeper’s wife in the 1870s. Numerous keepers and their families documented unexplained phenomena including mysterious footsteps, doors opening and closing without explanation, and occasionally glimpses of a female figure near the tower during storms.

One particularly intriguing account from 1912 describes how the three children of assistant keeper James McNamara simultaneously developed high fevers followed by delirium in which all three independently reported conversations with “the blue lady” who correctly predicted the arrival of a supply vessel three days early. Such occurrences were taken seriously enough that several relief keepers reportedly refused extended assignments at the station.

More verifiable is the tragic story of Senior Keeper Joseph Anderson who died at the station in 1889 after falling from the tower during routine maintenance. According to station records, subsequent keepers frequently reported hearing scraping sounds on the tower stairs on the anniversary of his death, described as similar to the sound of a body being dragged upwards.

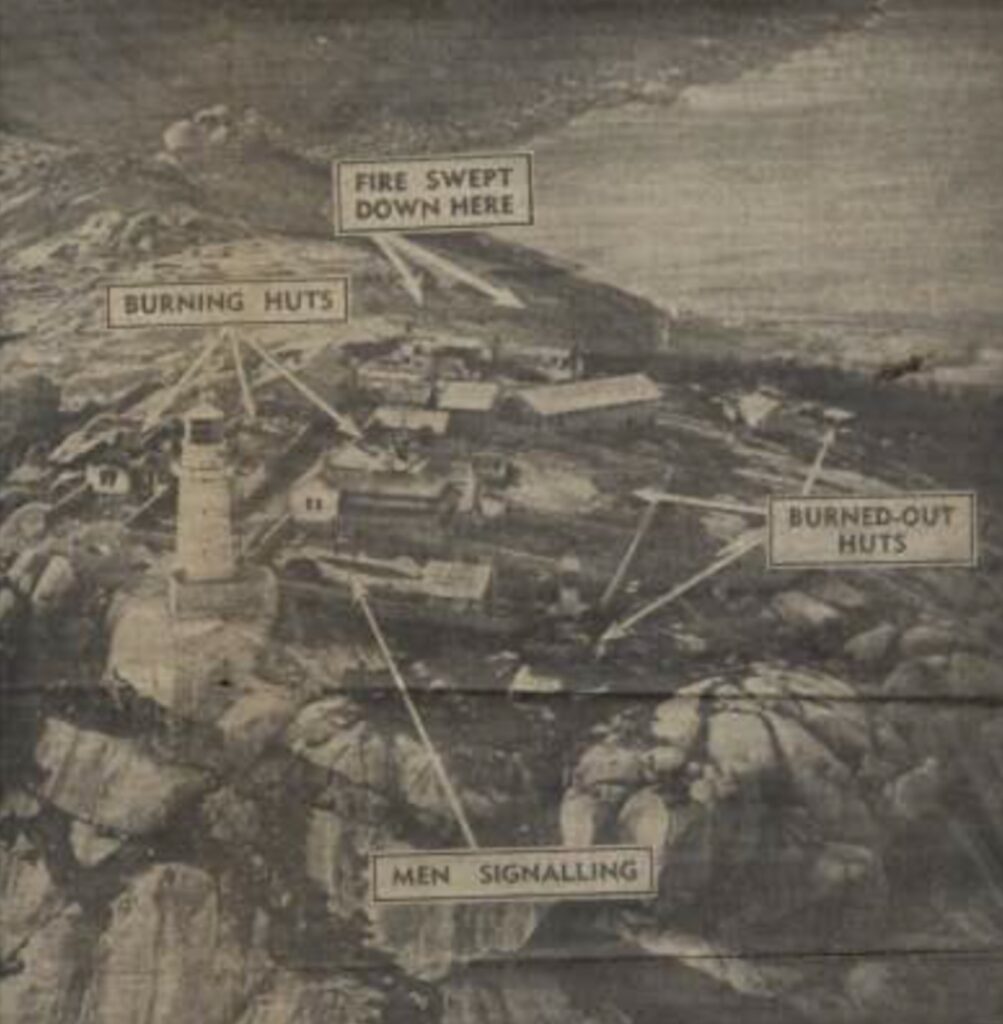

A more recent disaster occurred in 1951 when a fire burned through the park destroying all the wooden buildings at the lighthouse including the radio shack and telephone line, completely isolating those on station for over 6 months until communications were restored. The fire is believed to have been caused by an escaped ‘billy fire’ at Tin Pot Waterhole outside the northern boundary of the park and as a result all fires are now prohibited in the park.

Despite automation ending the resident keeper tradition, the lighthouse found new purpose. In 1996, Parks Victoria assumed management responsibility for the historic complex, eventually developing a program that allowed small groups of visitors to stay in the refurbished keepers’ quarters. This initiative has enabled people to experience something of the isolation and spectacular natural setting that defined life at this remote station, while ensuring the preservation of this significant heritage site.

Today, Wilsons Promontory Lighthouse represents one of Australia’s most important maritime heritage sites. The complete lighthouse station, with its original tower, keepers’ quarters, and various outbuildings, offers an exceptionally well-preserved example of a mid-Victorian lighthouse complex. The site’s remote location has paradoxically helped preserve its authentic character, with fewer modifications than many more accessible lighthouses.

The lighthouse remains an active with its automated light still reaching out across Bass Strait each night. Its characteristic flash pattern, one flash every 15 second, continues to be recognised by mariners navigating these waters, maintaining an unbroken tradition of maritime safety spanning more than a century and a half.

A Personal Note:

For the second lighthouse in a row it was a case of “close but no cigar”! Arriving at Tidal River I enquired about hiking to the lighthouse only to discover it was 19km each way necessitating an overnight stay at the lighthouse, which required me to carry everything I’d need including bedding and food. That presented a bit of a problem as I was ill equipped, the weather wasn’t great and it was booked out anyway!

The ranger then suggested I check with Wanderer Adventures who ran a boat trip to the lighthouse and nearby islands, including the scary looking skull rock every Wednesday, and it happened to be Wednesday! I hurriedly made my way over to them only to discover that today’s trip had been cancelled due to bad weather and sea conditions. Janice and Dave, the operators, were sympathetic to my cause and suggested I call them next Tuesday (29/4) to check if they’d be running the following day.

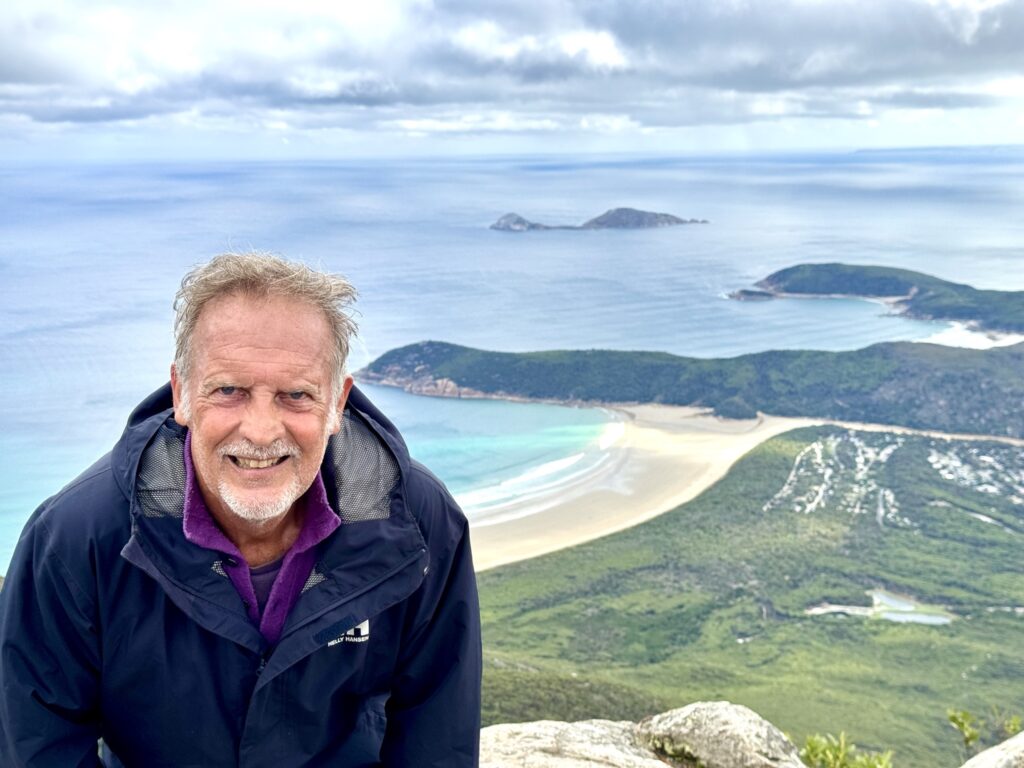

In order to make the most of my time here I climbed the imposing Mt. Oberon, which was a pretty hard slog, 3.9km all uphill, hoping to get a glimpse of the lighthouse which I didn’t but the view overlooking the promontory was breathtaking and it was pretty cool (both meanings of the word) when the clouds enveloped us and reduced visibility to about zero, only to blow by and re-reveal the amazing outlook. Thankfully the trek down the mountain was much easier and I couldn’t help thinking how I’d handle a 38km trek to the lighthouse and back if the opportunity came up? I also took the opportunity to visit some of the beautiful deserted beaches and decided, one way or another, I’ll be coming back.

I checked with Janice yesterday and unfortunately they didn’t have the numbers they needed to make it viable and have cancelled again. Janice was very apologetic and as a last resort suggested I contact the rangers and see if I can hitch a ride with them when next they go to service and maintain the cottages at the lighthouse, which is evidently a fairly frequently. She gave me the number for the ranger station and I spoke to a lady called Hayley from Parks Victoria who said it was an unusual request that they’d normally refuse but she’d pass on my details to the rangers and see if they might agree, with the proviso that it was a very long shot. I said I understood that but it was the only shot I had! As I write now I’m still waiting and hoping against hope that I might be able to get there and I’ll update this post if I do but in the interest of moving on I’m posting this now. Stay tuned!