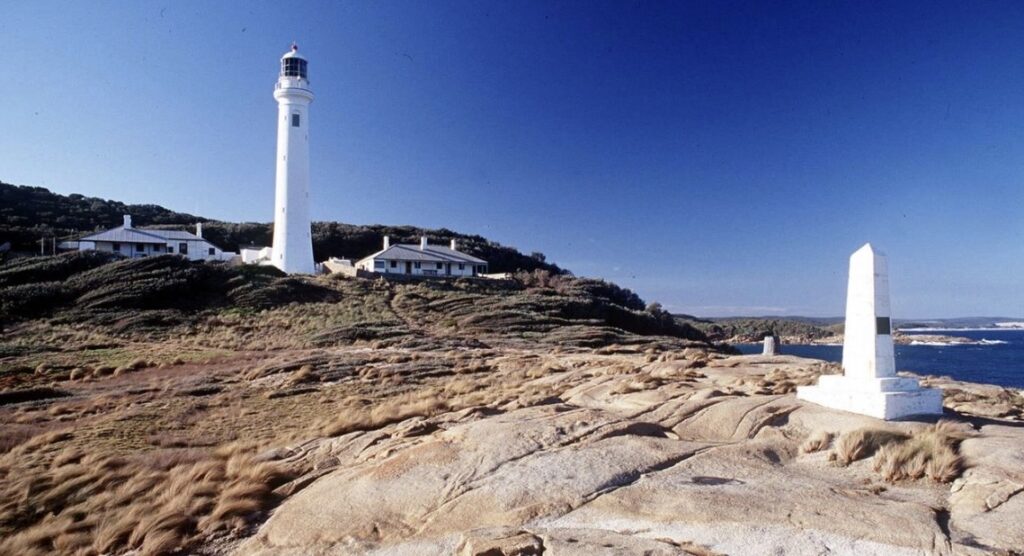

Point Hicks Lighthouse marks a site of profound historical significance, the first point of mainland Australia sighted by Lieutenant James Cook aboard the HMS Endeavour in 1770, a moment that would forever alter the course of the continent’s history.

Positioned on Victoria’s remote eastern coastline Point Hicks Lighthouse is one on three charged with the responsibility of guiding ships along one of Australia’s most dangerous coasts, an area renown for its sudden violent storms and treacherous seas, a rugged coast dotted with many islands and reefs where the warmer waters of the Tasman Sea collide with the cold waters of Bass Strait.

This was also the busiest shipping lane in Australia and securing safe passage along the southeastern seaboard during an era when shipping represented the nation’s primary means of transport and provided a vital connection to the wider world was of critical importance to our young nation.

Completed in 1890 as part of Victoria’s comprehensive coastal lighting scheme, Point Hicks Lighthouse was designed by the Victorian Public Works Department under engineer Carlo Catani. The lighthouse embodies the distinctive characteristics of late Victorian lighthouse architecture with its graceful proportions and meticulous attention to both function and form. Rising 39 meters from base to lantern, it stands as the third tallest lighthouse in Australia, its impressive height necessitated by the need to project its beam over the surrounding forest and far out to sea.

The lighthouse’s construction represented a remarkable logistical achievement given its remote location. With no roads reaching the site, all construction materials—thousands of granite blocks, tons of cement, intricate ironwork, and the delicate optical apparatus—had to be transported by sea. Ships anchored offshore while materials were laboriously transferred to small boats, landed on the beach, and then hauled up steep terrain to the construction site. This arduous process stretched over several years before the lighthouse finally cast its inaugural beam across the waters in May 1890.

The lighthouse tower’s elegant design features a gradually tapering cylindrical form constructed from locally quarried granite blocks, each precisely cut and fitted to create a structure of exceptional strength and durability. The tower’s thickness at its base—walls measuring nearly two meters—reflects the engineers’ understanding of the extreme forces this isolated sentinel would face during coastal storms. The exterior was rendered and painted bright white to maximize visibility against the often dark and stormy skies characteristic of this coastline.

Point Hicks was equipped with a state-of-the-art first-order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, the largest and most powerful category of lighthouse optic available at that time. The massive prismatic lens assembly, manufactured in Birmingham, England, and shipped to Australia concentrated the light from a kerosene vapor lamp into an intense beam visible from approximately 26 nautical miles at sea. The optical apparatus, weighing several tons, rotated on a bed of mercury to create the lighthouse’s distinctive flashing pattern—three flashes every thirty seconds—that allowed mariners to positively identify this particular lighthouse.

The lighthouse station was designed as a self-contained community, necessarily self-sufficient due to its extreme isolation. The complex included substantial accommodations for three lighthouse keepers and their families, with the head keeper occupying the largest residence befitting their status as the station’s commanding officer. Supporting structures included a workshop, stables, storage facilities, and a small school room where the keepers’ children received their education.

Life for those stationed at Point Hicks was defined by its remoteness. The nearest settlement was many days’ journey away through dense coastal forests, making regular supply deliveries crucial lifelines. These came by sea every three months, weather permitting, bringing not only essential provisions but also mail and news from the outside world. For the keepers and their families, this isolation fostered an extraordinary resilience and self-reliance that became the hallmark of lighthouse communities.

The isolation that defined life at Point Hicks was magnified by the surrounding wilderness. The lighthouse stands within what is now recognised as one of Australia’s most pristine coastal environments, with the keepers serving as unofficial stewards of this remarkable ecosystem. Beyond their maritime duties, they often aided shipwreck survivors, monitored weather patterns, and recorded observations of the abundant wildlife that inhabited the surrounding forests and waters.

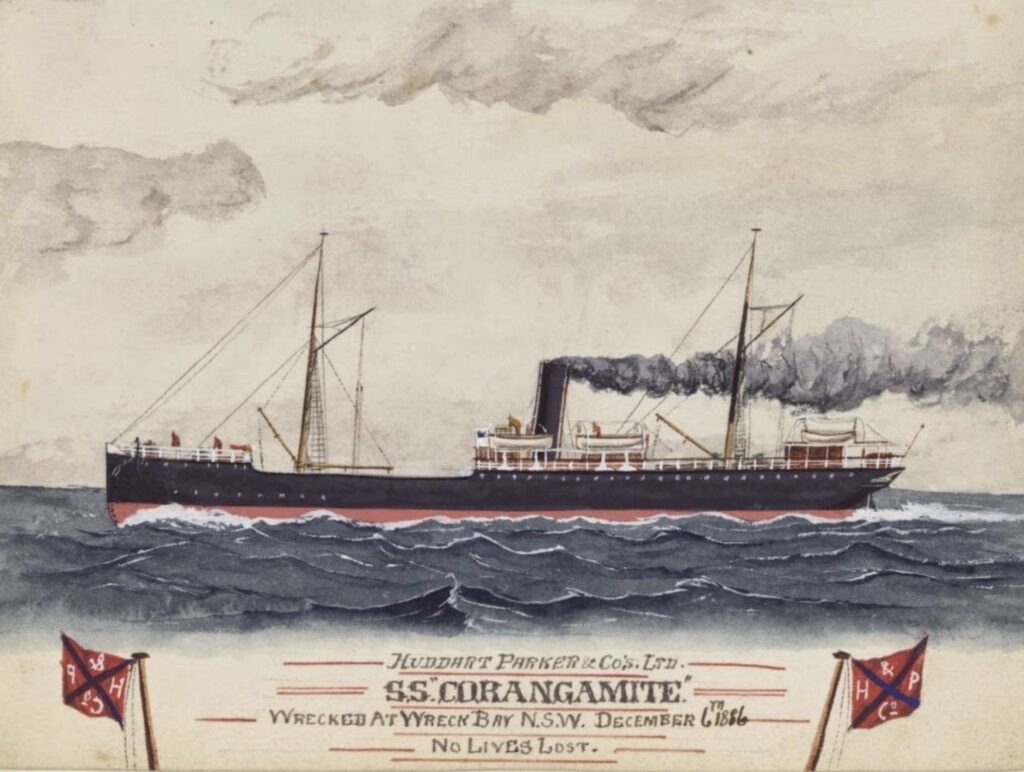

The waters off Point Hicks have claimed numerous vessels throughout history, each wreck adding to the lighthouse’s purpose and legacy. Most notorious was the loss of the SS Saros in 1937, which ran aground on a reef during heavy fog just kilometers from the lighthouse. Despite the proximity of the light, conditions rendered it ineffective that fateful night. The lighthouse keepers coordinated rescue efforts, recovering survivors and providing emergency aid. This tragedy, like others along this coast, underscored the continuing dangers of maritime travel even in the modern era.

Archaeological surveys have identified multiple shipwreck sites in the vicinity of Point Hicks, many dating to the pre-lighthouse era when this treacherous coastline claimed vessels with alarming regularity. These underwater time capsules, now protected heritage sites, provide valuable insights into colonial-era shipping and trade patterns, while serving as somber reminders of the human cost that justified the lighthouse’s construction.

Like many remote lighthouses with histories intertwined with tragedy, Point Hicks has accumulated its share of folklore and supernatural tales. Most persistent are accounts of mysterious footsteps ascending the tower stairs on storm-tossed nights when all keepers were accounted for. Some attribute these phenomena to the ghost of assistant keeper Robert Christoferson, who died at the station in 1947 after a tragic accident. After being discharged from the Army in 1945, Christoferson sought sanctuary and seclusion as an assistant keeper at Point Hicks. After his mysterious disappearance, numerous residents and visitors attest that the ghost of Christoferson occupies his former cottage: his hobnail boots are heard around the tower at night and his apparition polishes brass doorknobs and moves tools and other objects about the lighthouse. His grave, located in the lighthouse grounds, serves as a poignant reminder of the isolation that could transform routine accidents into life-threatening emergencies.

The lighthouse’s connection to Captain Cook’s historic first sighting of eastern Australia adds another significant dimension to its historical importance. On April 19, 1770, Cook recorded in his journal the sighting of “a point of land which I have named Point Hicks because Lieutenant Hicks was the first who discovered this land.” While controversy has surrounded the exact location of Cook’s sighting, the lighthouse has become the symbolic marker of this pivotal moment in Australian history.

Today, Point Hicks Lighthouse stands as one of Australia’s most significant maritime heritage sites, protected within the Croajingolong National Park and recognized on the Commonwealth Heritage List. The complete lighthouse station, with its original tower, keepers’ residences, and outbuildings, presents an exceptionally well-preserved example of late Victorian lighthouse architecture and engineering. Its continuing operation makes it not merely a museum piece but a living link to Australia’s maritime past.

A Personal Note:

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to visit Point Hicks as the only access road has been closed since the disastrous bushfires of 2020 which burnt out several wooden bridges. As disappointing as this was it has made my next adventure, to retrace Captain Cooks voyage along the east coast of Australia all the more important as Point Hicks will mark the start of this journey.