Situated at the southernmost point of New South Wales before the coastline curves westward toward Victoria, the imposing tower of Green Cape Lighthouse has served as a crucial navigational beacon along Australia’s treacherous southeastern coastline for almost 150 years.

The lighthouse was commissioned and first lit in 1883 following a series of devastating shipwrecks along this notorious stretch of coastline. However, ironically the worst tragedy occured after the lighthouse was operational with the loss of the steamship Ly-ee-Moon in 1886, which struck rocks virtually beneath lighthouse. This maritime disaster, which claimed 71 lives, including Flora MacKillop, mother of Sister (now Saint) Mary, who evidently visited and blessed her mother’s grave in the Ly-ee-Moon Cemetery near the lighthouse.

Designed by renowned colonial architect James Barnet, who was responsible for many of Australia’s finest lighthouses Green Cape represents the height of Victorian lighthouse design and engineering. Unlike its more modestly sized counterparts the lighthouse towers an impressive 29 meters from base to lantern, making it the tallest lighthouse in New South Wales at the time of its completion. Its construction demanded extraordinary effort, with materials painstakingly transported to this remote location by sea and then hauled up steep cliffs before assembly could even begin.

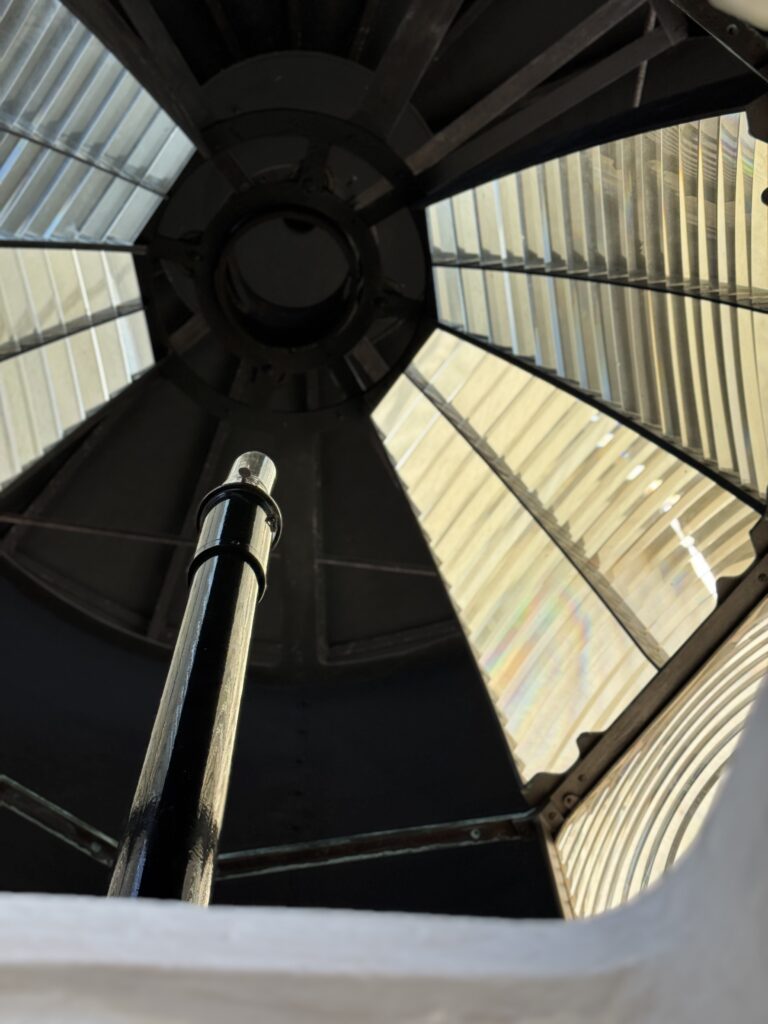

The lighthouse’s architecture reflects both beauty and functionality in equal measure. Constructed from locally quarried granite blocks and imported concrete the lighthouses unique design, transitioning from a square base to an octagonal tower provides both structural integrity against fierce Bass Strait storms and a distinctive silhouette visible from considerable distances. Its gradually tapering form culminates in an elegant lantern room housing one of the most powerful optical apparatuses installed on the Australian coast to that time. It’s also said that Barnet took inspiration from middle eastern architecture for the domed roof of the attached keepers office.

The gleaming white exterior, serves the practical purpose of maximizing visibility against dark skies, while the solid construction speaks to the Victorian engineers’ determination to build a structure that would withstand the extreme coastal conditions for generations to come. The lighthouse and its associated keeper’s quarters represent a complete colonial lighthouse station, carefully designed to be self-sufficient in this remote location.

Initially equipped with a first-order dioptric lens manufactured by the renowned Chance Brothers of Birmingham, the light was fuelled by kerosene and could project a beam visible for approximately 20 nautical miles. This powerful illumination provided crucial guidance to vessels navigating the shipping routes between Sydney and Melbourne, as well as international traffic moving along Australia’s eastern seaboard. The lighthouse underwent significant technological transitions throughout its operational history. The original kerosene lamp was replaced by a vapor burning system in the early 20th century, followed by conversion to electric operation in 1962. In 1992, the lighthouse was fully automated, ending over a century of continuous human presence at the station.

Life for the keepers at Green Cape was marked by extraordinary isolation, the nearest settlement of any size, Eden, lay some 35 kilometres away, accessible initially only by sea or via a rough bush track. This isolation required the lighthouse station to function as an essentially autonomous community. The station included substantial accommodations for three lighthouse keepers and their families, arranged in a distinctive semi-detached configuration that reflected the hierarchy among the staff.

Weather extremes tested both the lighthouse and those who maintained it far more severely than at many other locations. Green Cape’s position at the convergence of the Eastern Australian current flowing from the north and the colder waters of Bass Strait coming from the west combine to create very treacherous sea conditions and extraordinarily powerful storms, with winds recorded at over 150 kilometres per hour and waves that could send spray higher than the tower itself. During the worst conditions, keepers sometimes maintained continuous watch, ensuring the light remained operational through even the most severe tempests.

The waters surrounding Green Cape have claimed numerous vessels over the centuries, earning this stretch of coastline an ominous reputation among mariners. The aforementioned Ly-ee-Moon disaster remains the most notorious shipwreck associated with the area, but numerous other vessels have met their end on the treacherous reefs and submerged rocks that lurk offshore.

Two of the more notable tragedies were of the SS City of Sydney in 1862 and the SS New Guinea in 1911, both claiming multiple lives and both occurring in the appropriately named Disaster Bay which is adjacent to the lighthouse. Even after the lighthouse began operation, the unpredictable and often violent seas of the area occasionally proved too challenging for ships in distress. The lighthouse keepers frequently found themselves first responders to maritime emergencies, organising rescue efforts and providing initial aid to survivors.

The lighthouse’s log books document dozens of dramatic rescues where keepers placed themselves at considerable personal risk to assist stricken vessels, launching small boats into turbulent seas or descending treacherous cliffs with ropes to reach survivors. These acts of heroism form an important chapter in the lighthouse’s history, emblematic of the broader role lighthouse keepers played in maritime safety beyond merely maintaining the light itself.

Like many isolated lighthouses with histories of tragic shipwrecks, Green Cape has accumulated a rich folklore of supernatural occurrences and mysterious tales. The most persistent involves reports of ghostly apparitions believed to be victims of the Ly-ee-Moon disaster. Keepers and their families recorded unexplained footsteps in empty corridors, mysterious knocking sounds, and occasionally glimpses of figures that vanished when approached.

One particularly chilling account from the 1920s describes a keeper’s young daughter who developed a friendship with an “invisible woman” who would speak to her near the cliff edge where many Ly-ee-Moon victims had been recovered. The child reportedly described details of 1880s clothing and life that she could not possibly have known.

More verifiable is the tragic story of assistant keeper Henry Gustavus Baumgarten, who died at the station in 1885 after a horse-riding accident. According to station records, his ghost was so frequently reported by subsequent keepers that it was almost considered another resident of the station, particularly on stormy nights when footsteps would allegedly be heard climbing the tower stairs, even when all keepers were accounted for.

As maritime navigation underwent revolutionary changes through the 20th century, Green Cape’s role evolved accordingly. The introduction of radar, satellite navigation, and automated systems gradually reduced the need for human keepers, though the lighthouse’s powerful beam remained an important backup to electronic aids. The 1992 automation marked the end of an era, as the last keepers departed the station that had been continuously inhabited since 1883.

Today, the Green Cape Lighthouse represents one of Australia’s most significant maritime heritage sites. The complete lighthouse station, with its original tower, keepers’ quarters, and outbuildings, offers an exceptionally well-preserved example of a late Victorian lighthouse complex.

On a personal note I was delighted to learn that plans are afoot to remove the awful skeletal iron tower that which superseded the lighthouse in 1994 and to instal a LED light inside the original lens, thereby reinstating the lighthouse to full operations in the near future. I understand this retrofitting is planned for several other lighthouses that have borne the insult of having their role taken over by a soulless meccano sets in the 1990’s. Another highlight on my visit was that I actually got to manually turn the lighthouse on (something I never thought I’d get to do)!

I love reading the history of these lighthouses and particularly enjoy learning the quirky side notes, like the ghost stories and any other info that brings current day relevance to these places of historical note.