Location:

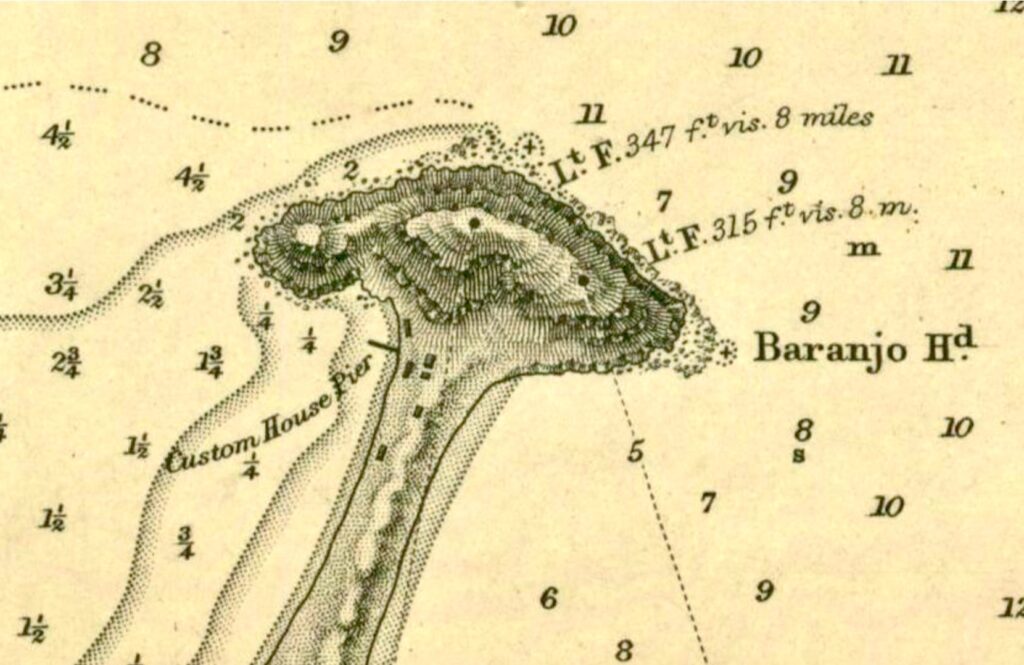

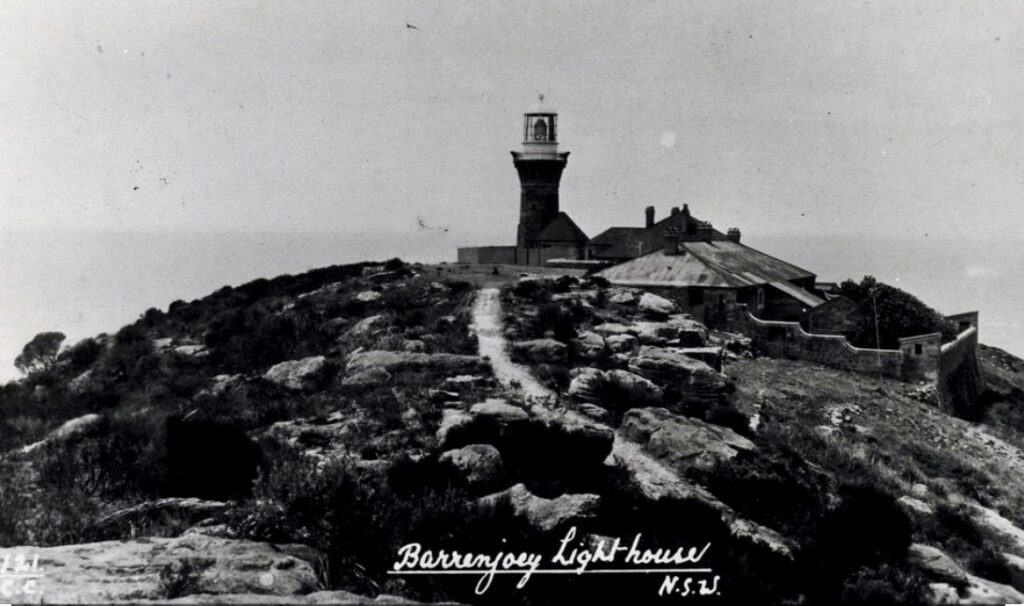

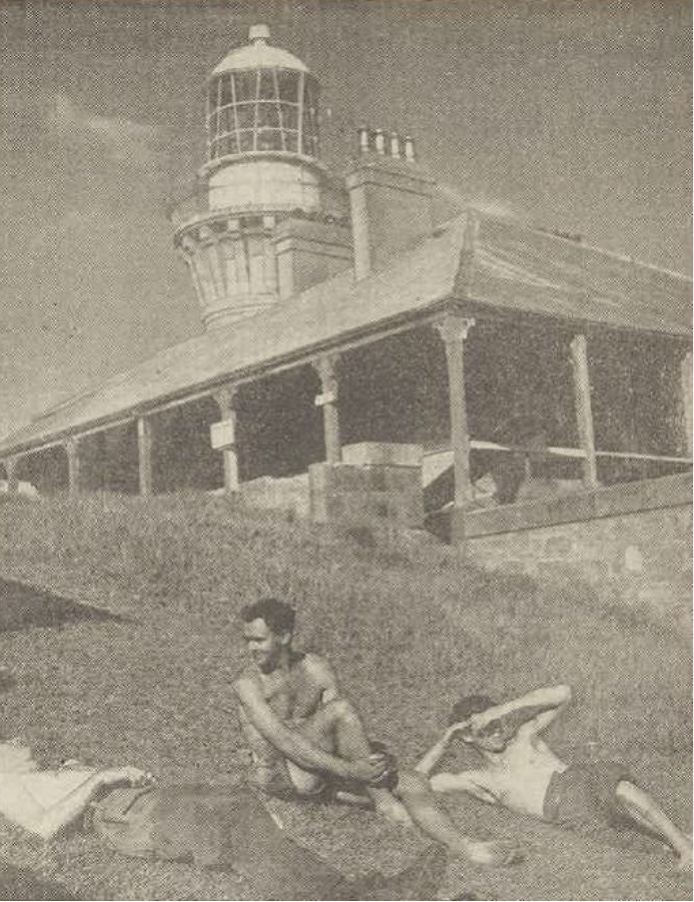

Marking the northern extremity of the Sydney metropolitan area Barrenjoey Lighthouse sits 113 meters above sea level and occupies a commanding position on Barrenjoey Head which together with the distinctive Lion Island forms the gateway to Broken Bay, where three major waterways converge; the Hawkesbury River to the west, Pittwater the south and Brisbane Waters to the north.

The headland itself is a striking geological feature, an island in prehistoric times it is now connected to the mainland by a narrow sandy isthmus. This natural formation creates a distinctive landmark that has guided maritime traffic for generations. The lighthouse’s elevated position offers panoramic views in all directions, over the Pacific Ocean and inland waterways further west to Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. However, this also makes it particularly vulnerable to severe weather conditions, especially during the east coast low pressure systems that frequently batter this stretch of coastline. Wind speeds at the summit can exceed 100 km/h during storms, while salt spray and extreme temperature variations test both the structure and those who maintained it.

The strategic position of the lighthouse ensures its beam can reach vessels up to 19 nautical miles out to sea and provides crucial guidance for ships navigating the often treacherous waters around Broken Bay.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 33° 34’S Long: 151° 19’E

First Lit: June 29, 1881 (Automated 1932, Demanned 1932)

Tower height: 21 meters

Focal Height: 113m above MSL

Original Lens: First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens

Intensity: 750,000 candela

Range: 19 nautical miles

Characteristic: Four White flashes every 20 seconds [Fl.(4)W. 20s]

Indigenous History:

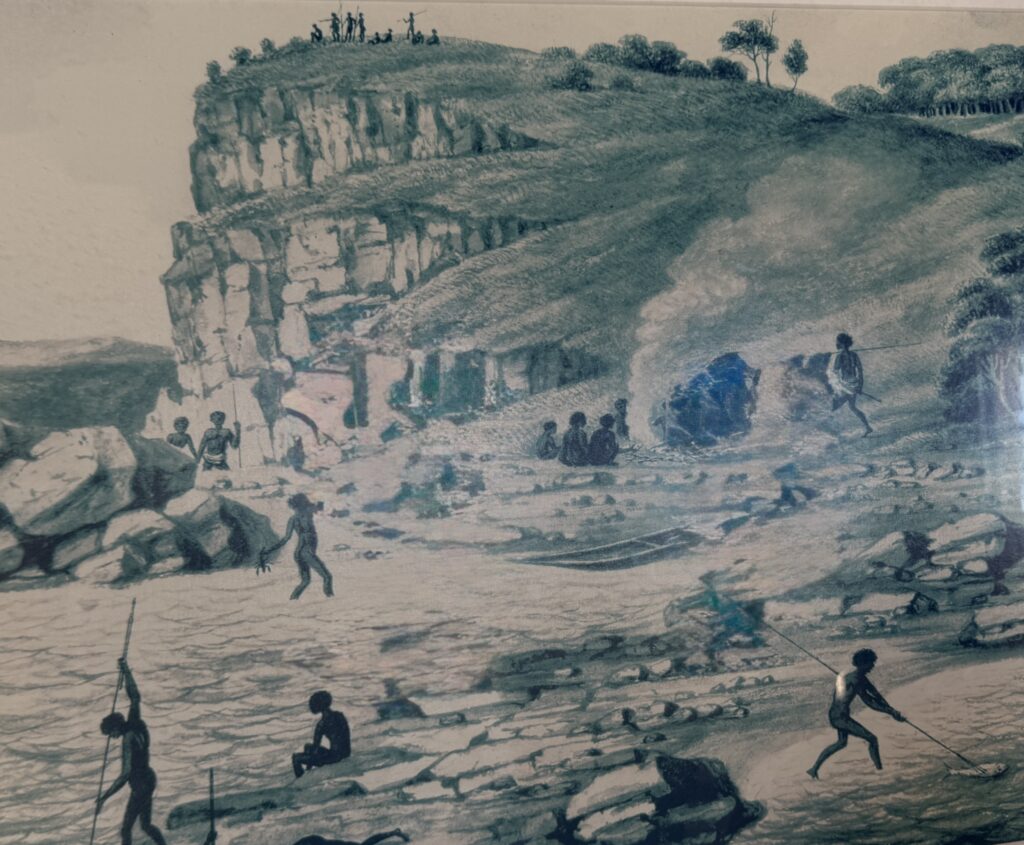

The Garigal people of the Eora Nation are the Traditional Owners of Barrenjoey Head, known to them as “Barrenjuee” or “Little Wallaby.” For countless generations before European settlement, this prominent headland served as an important meeting place and lookout point for Aboriginal people.

Archaeological evidence reveals a rich history of Indigenous occupation spanning thousands of years. Extensive rock art and shell middens discovered around the headland contain not just the remains of meals but also tell dreamtime stories dating back thousands years and provide valuable insights into pre-colonial life and the First Australians relationship to their environment.

The Garigal people developed intricate knowledge on their environment including an understanding of weather patterns and marines and native animal behaviours. The headland played a crucial role in their customs and ceremonies, particularly during whale migrations when it served as an ideal vantage point for tracking these sacred creatures.

The connection between the Garigal people and Barrenjoey Head continues today, with Traditional Owners maintaining cultural links to this significant landscape and sharing their knowledge through educational programs and cultural activities.

Colonial History:

European attention first turned to Barrenjoey Head following Governor Phillip’s exploration of Broken Bay in 1788. The strategic importance of the headland was recognized early, as it controlled access to both the Hawkesbury River system and the sheltered waters of Pittwater and Brisbane waters.

The discovery of arable land with abundant fresh water meant the Hawkesbury River valley became the food bowl of the colony with a resultant increase in shipping between Broken Bay and Port Jackson, and Barrenjoey was an important way point on this voyage.

The first European structure on the headland was a customs house established in 1843 to combat widespread smuggling in the area. The growing maritime trade along the coast, particularly the increasing traffic of vessels serving the Hawkesbury River settlements, led to the establishment of a navigation beacon in 1855. Initially, this consisted of a fire in a basket atop a wooden tripod, maintained by customs officers. By 1868, this crude arrangement was replaced by a proper red light mounted on a wooden tower, which served until the construction of the current lighthouse.

The name “Barrenjoey” itself has an interesting etymology. While clearly derived from the Aboriginal “Barrenjuee,” early colonial records show various spellings including “Barranjuee” and “Barranjoey.” The current spelling was officially adopted in 1866.

The Lighthouse:

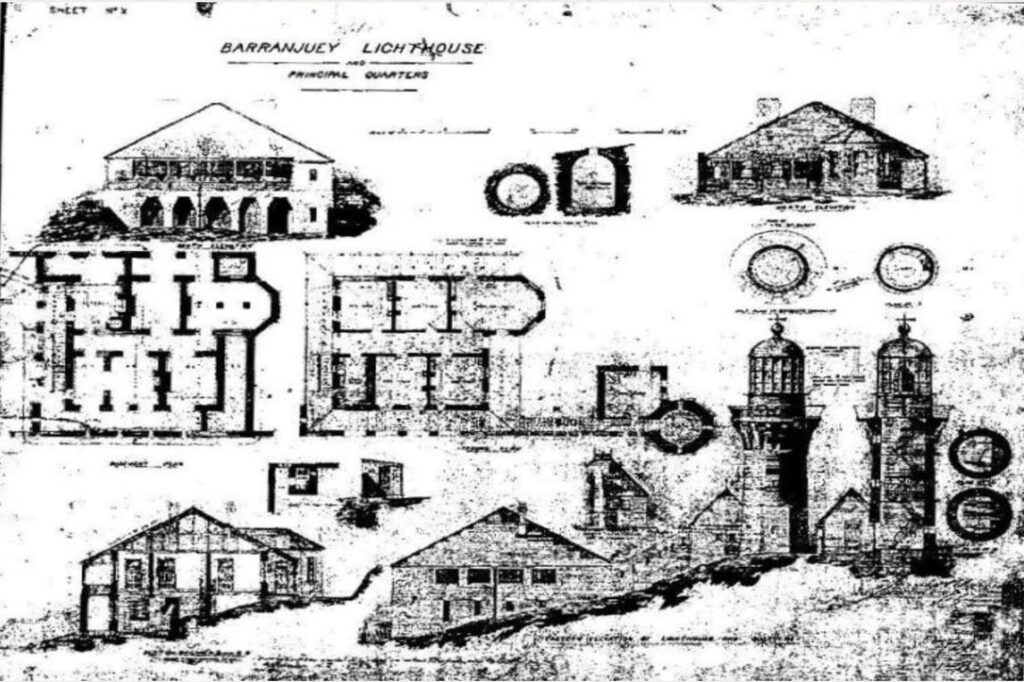

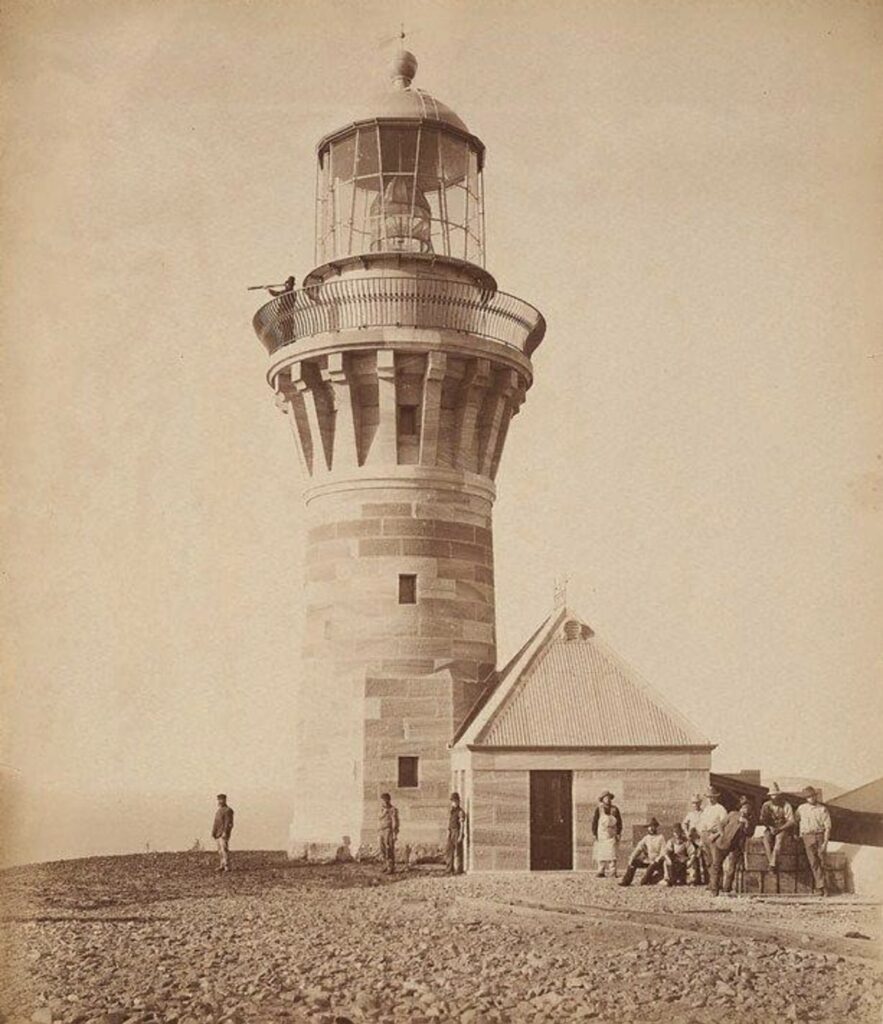

James Barnet’s design for Barrenjoey Lighthouse exemplifies his mature lighthouse architectural style, incorporating elements refined through his previous lighthouse projects along the NSW coast. The tower was constructed from locally quarried sandstone, with blocks carefully selected and cut on site. This local stone gives the lighthouse its distinctive honey-coloured appearance, differentiating it from the painted white towers more common along the coast.

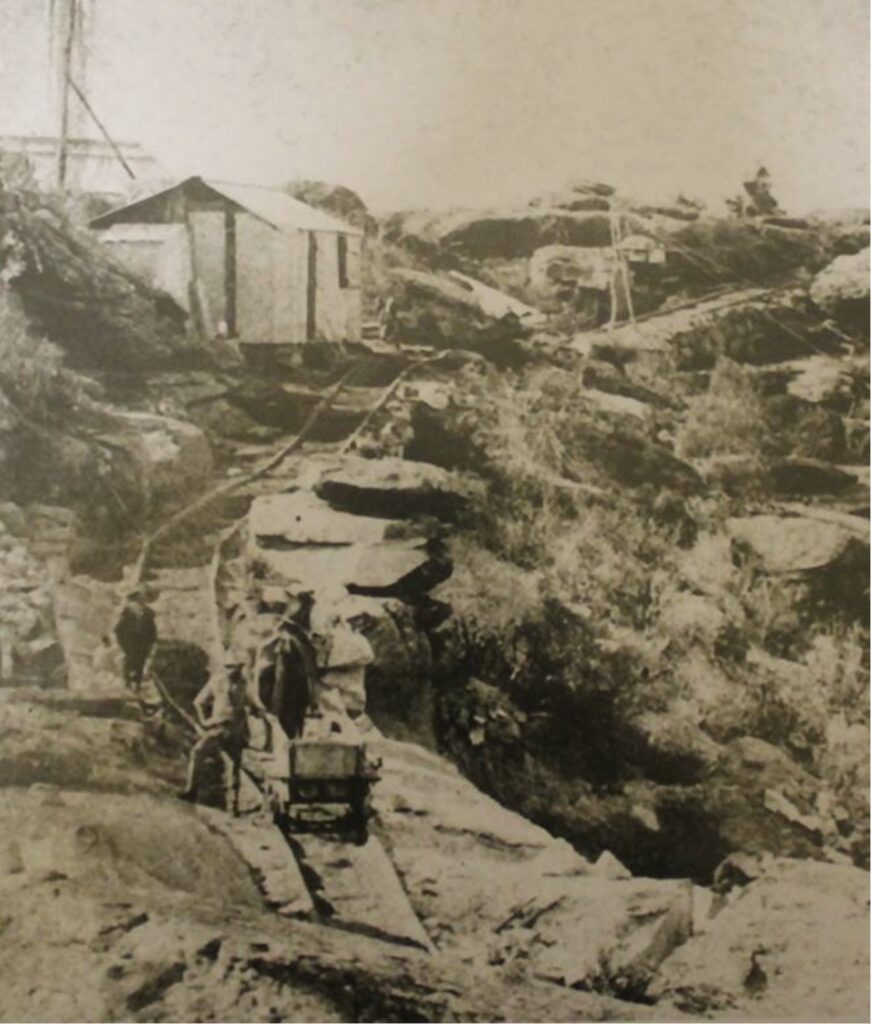

Construction commenced in 1880 under the supervision of Isaac Banks, presenting unique challenges due to the site’s accessibility. A flying fox system was established to transport materials from the beach to the construction site. Local historical accounts suggest that much of the stone was quarried from the western side of the headland, with a temporary tramway constructed to transport blocks to the building site.

The lighthouse was officially lit on June 29, 1881, equipped with a state-of-the-art First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens. Its characteristic white flash every 15 seconds would become a familiar and reassuring sight to generations of mariners navigating these waters.

The Buildings:

The lighthouse tower stands 21 meters high and was constructed from sandstone blocks quarried from the headland itself. The tower’s walls are nearly a meter thick at the base, tapering as they rise. The design incorporates several distinctive features of Barnet’s architectural style, including the gunmetal railing and bracketed gallery walkway.

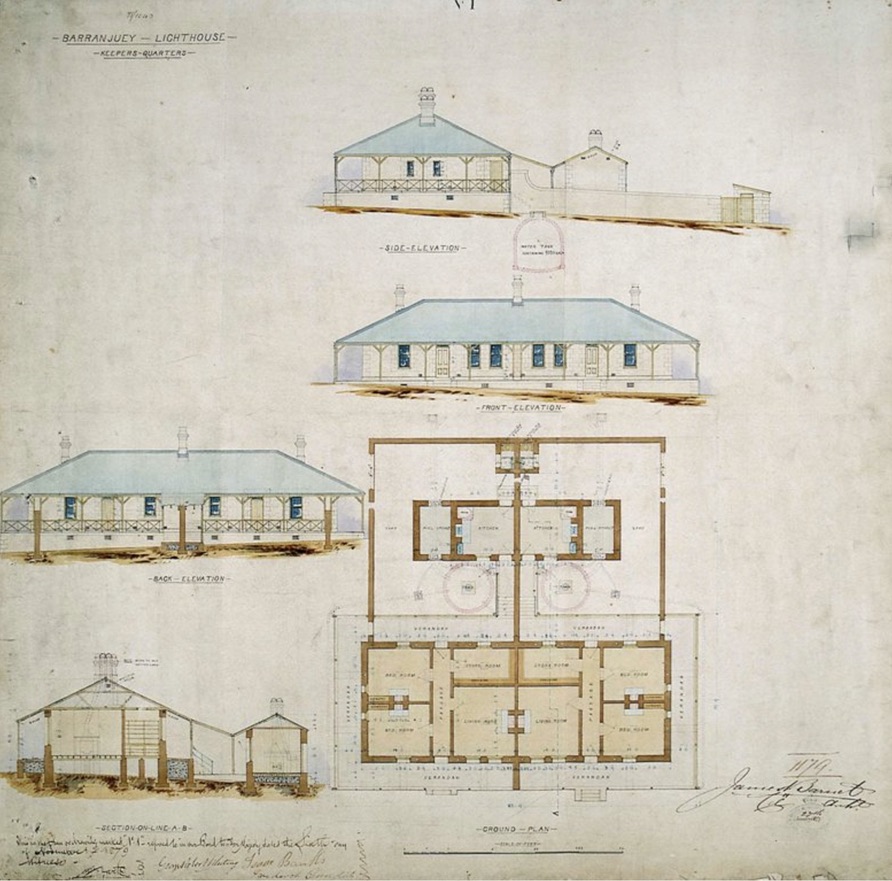

The lighthouse complex includes the main tower, keeper’s quarters, and various outbuildings all constructed from the same local sandstone. A unique feature of Barrenjoey is its two keeper’s cottages built in a Victorian Georgian style, positioned to provide both comfort and functionality for the lighthouse families while maintaining clear sight lines around the tower.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the lighthouse’s construction was the system of flying foxes used to transport materials up the steep headland. Evidence of this innovative construction technique can still be seen in the rock face today.

Technical Details:

The original lighting apparatus consisted of a First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens, a masterpiece of Victorian engineering that remains in place today. This sophisticated optical system stands 2.6 meters tall and contains hundreds of hand-ground glass prisms arranged in a beehive pattern to focus the light into an intense beam.

The original light was a fixed red light which was converted to a flashing white light with the characteristic of 4 white flashes every 20 seconds when the light source was upgraded to acetylene in 1932.

When first installed, the light source was a Colza oil fuelled lamp which required constant attention from the keepers. This was converted to a pressurised kerosene vapor system in 1912 which remained in operation until 1932 when it was converted to acetylene gas and further converted to mains electricity in 1972.

Since then there have been a number of technical updates including automation, remote monitoring capabilities, the conversion the light source to 1,000watt tungsten halogen and more recently a LED light source with solar power in 1995 and improved backup power systems.

While the light source has changed over time the original First Order Chance Brothers lens (1881) remained in opertion and the only modification has been the installation of automated storm shutters protecting the lantern room glass from storm damage.

Keepers of the Light:

The story of Barrenjoey’s lighthouse keepers is one of extraordinary dedication, family sacrifice, and lives lived in relative isolation for the safety of others. Each keeper brought their own character to the role, while their families created a unique community atop the windswept headland, their daily routines dictated by the needs of the light and the rhythms of the sea below.

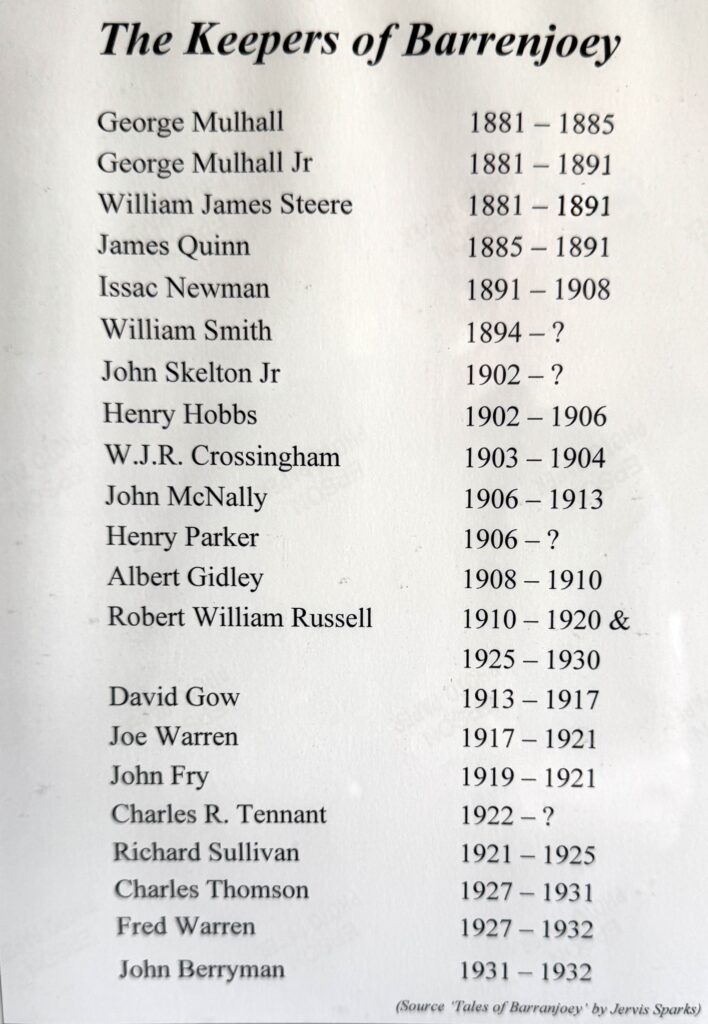

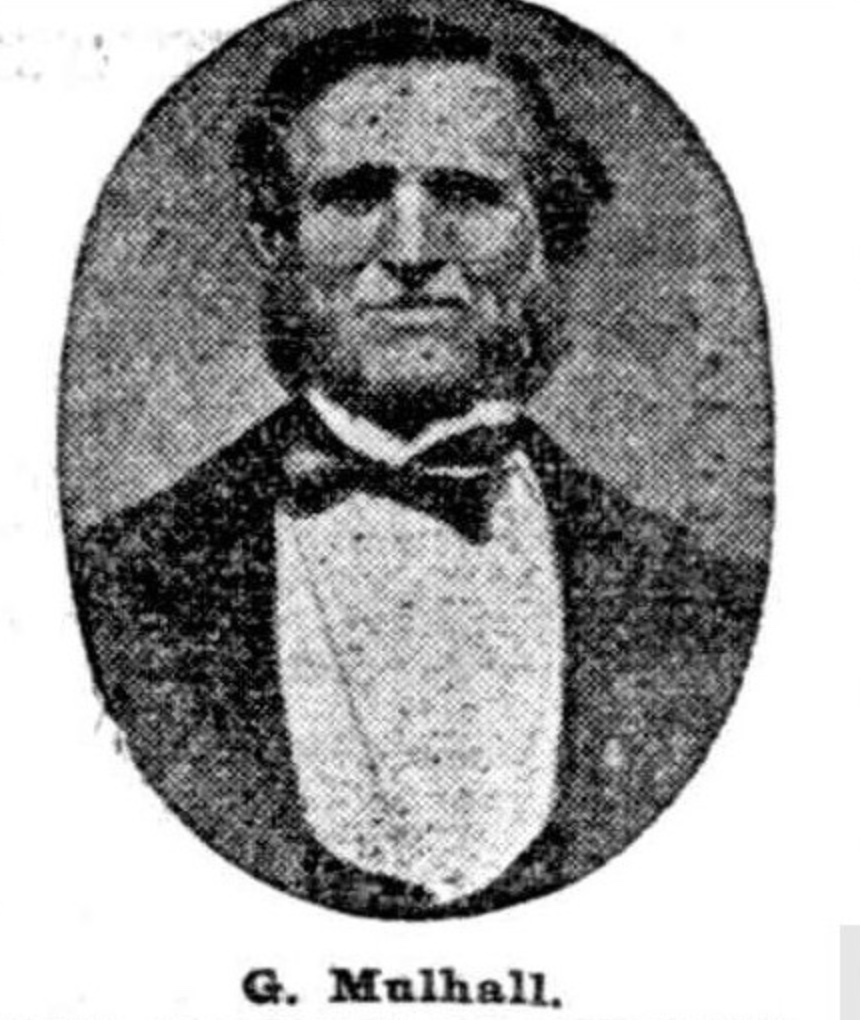

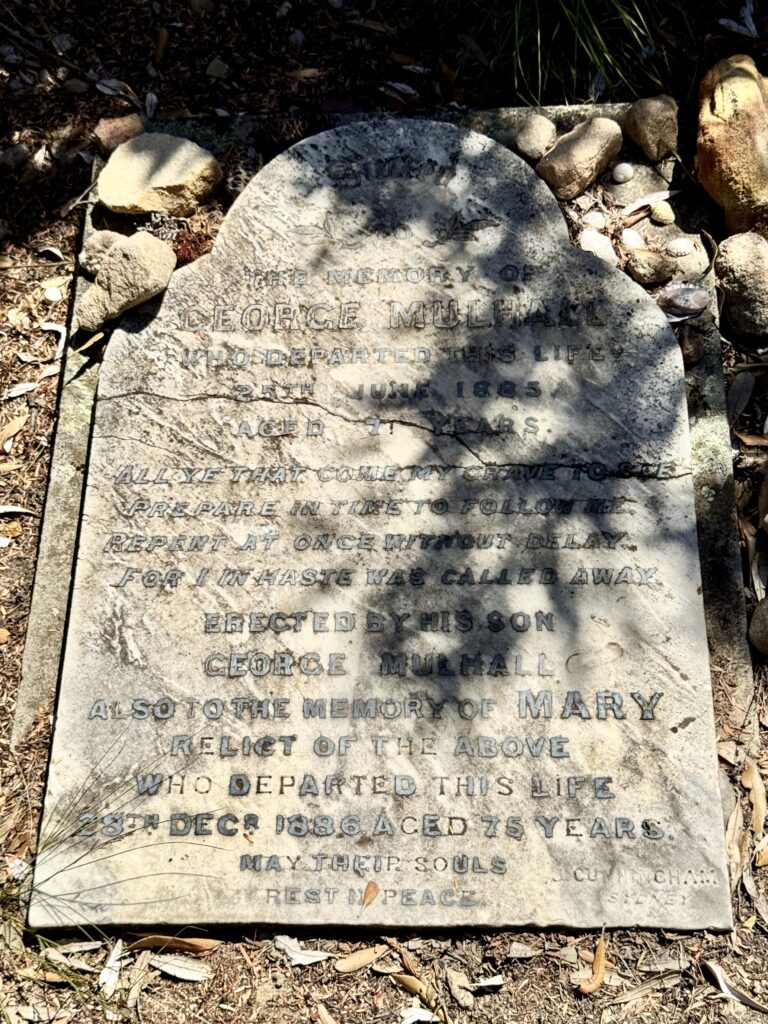

The is conjecture over whether Isaac Banks’ who oversaw the construction of the lighthouse and keepers cottages was also the first Head Keeper. There are conflicting accounts of whether it was Banks or George Mulhall were the first Head Keepers, however, with respect to the list above I will give Isaac Bank’s the benefit of the doubt and include the information I have seen on his tenure from 1881 to 1885.

Having overseen the lighthouse’s construction, Banks had an intimate knowledge of every aspect of the station and his personal diaries, preserved in the State Archives, reveal the immense challenges of those early years. Banks wrote of the struggle to establish supply lines, the difficulties of transporting fresh water to the summit, and his innovative solutions for maintaining the complex optical equipment. His wife Sarah established the station’s first vegetable garden, experimenting with different crops to determine what could survive in the salt-laden air. Their children, Tom and Mary, became the first of many lighthouse children to receive their education via correspondence, with Sarah serving as their teacher.

The story of the Mulhall family stands as one of the most compelling and tragic chapters in Barrenjoey’s history. George Mulhall Senior took up the position of Head Keeper in 1885, bringing with him a deep understanding of maritime operations gained from years of seafaring experience. His tenure, however, came to a dramatic and tragic end in 1885 when he was struck by lightning while checking the flagstaff during a severe storm. The incident occurred in full view of his family, including his son George Junior, who would later follow in his father’s footsteps as keeper.

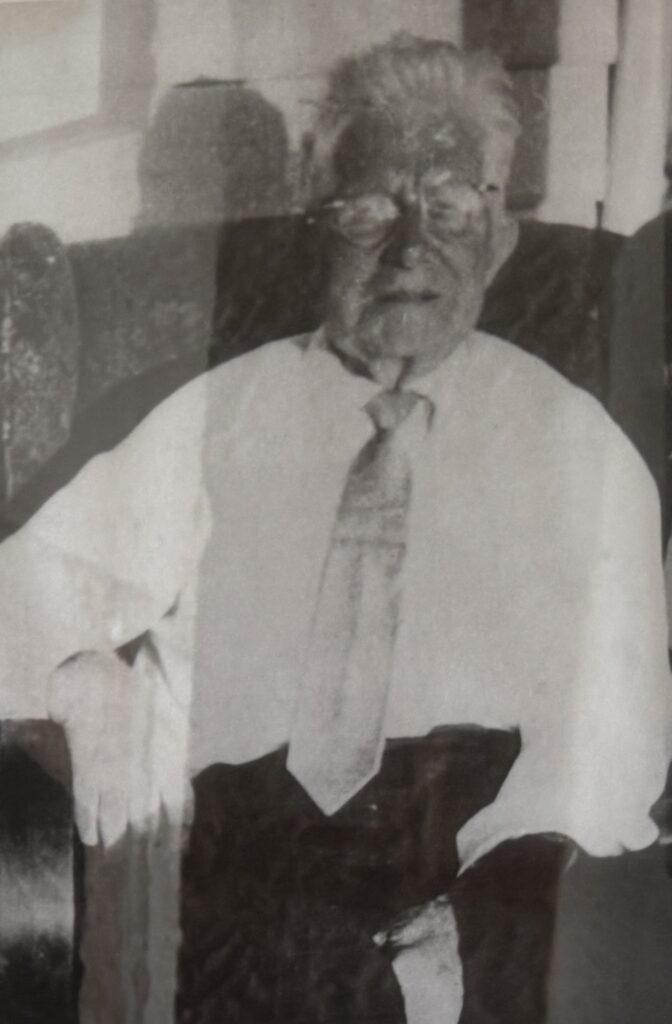

George Mulhall Junior’s appointment as Head Keeper in 1889 marked an unusual continuation of family tradition in lighthouse service. Stoically George’s widow Mary took over the duty’s of her late husband after his untimely death until their son, George Junior, was old enough to be appointed. Having grown up at the station and witnessed his father’s dedication and ultimate sacrifice, he brought a unique perspective to the role. Under his leadership, the station developed more sophisticated weather monitoring systems and improved rescue protocols. His wife Martha became known for her skill in treating injuries and illnesses, as the isolated location meant keeper families often had to manage medical emergencies without professional assistance.

This is where the Mulhall story gets really weird, maybe the truth is stranger than fiction!

Who said lightning doesn’t strike twice (or even three times)…

According to the graveside signage “On a stormy night in June, 1885, George Mulhall venturing out for more firewood, was struck down by a tremendous bolt of lightning, and as the journalism of that day recorded, was burnt to a cinder.”

Mulhall’s son, George Junior, the second lighthouse keeper 1881-1891, was in fact stuck by lightening resulting in a badly burnt arm and according to reports ‘from that day was bound in snake-skin to ward off further celestial visitations’. It is also reported (by the Sydney Morning Herald) that George Junior’s brother, an assistant keeper, was also killed, ‘almost entirely consumed’ by fire, when lightening hit one of the keepers houses in which he was staying on the evening of the 26 March 1888.

Henry Hobb’s tenure (1902-1906) coincided with significant technological advancements in lighthouse operation. Hobbs embraced these changes, developing new maintenance techniques for the increasingly complex equipment while maintaining the traditional skills essential for lighthouse operation. His detailed weather records proved particularly valuable for understanding local meteorological patterns, and his system of weather reporting was adopted by other lighthouses along the coast.

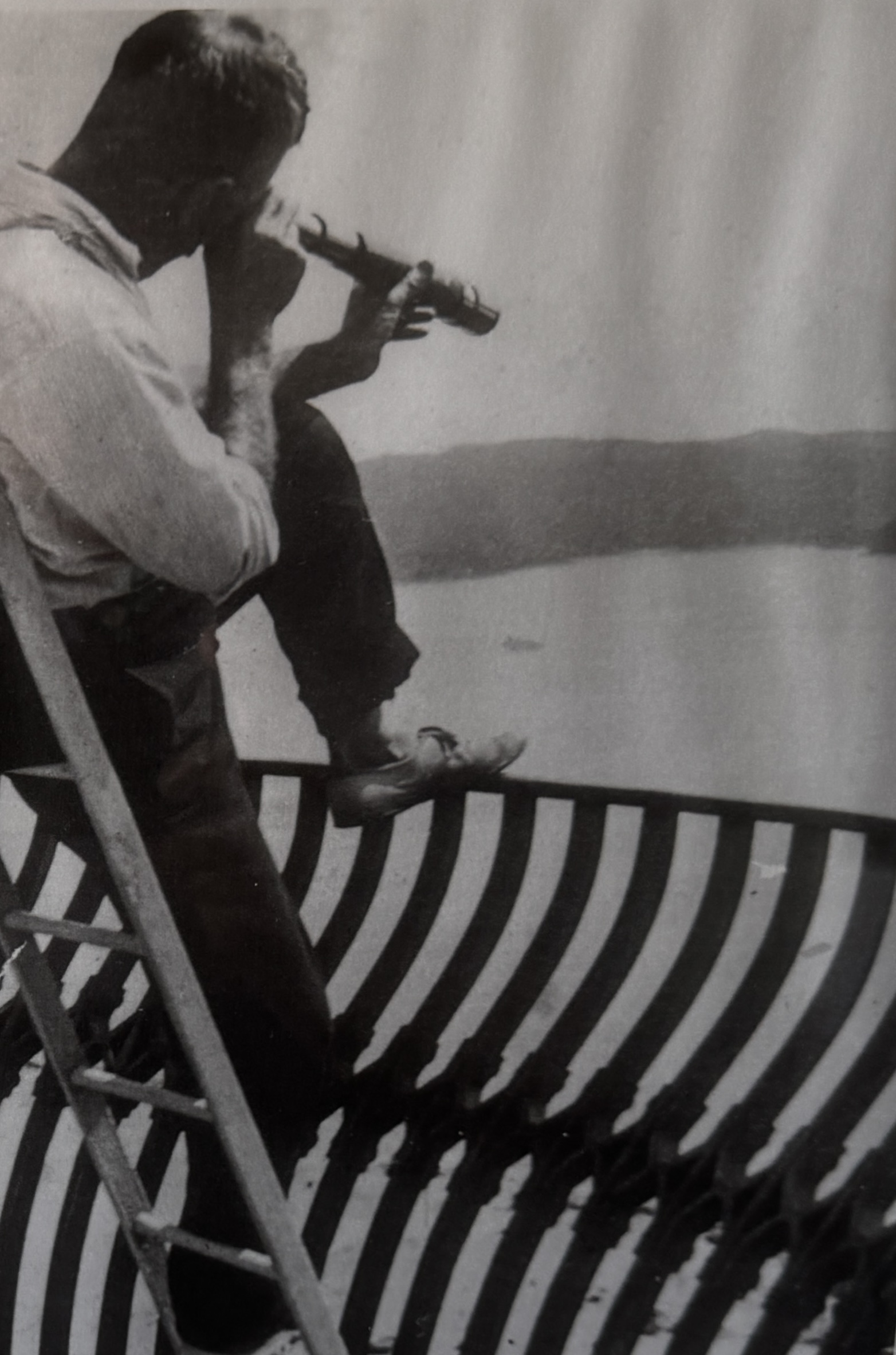

The First World War brought new challenges under Robert Russell’s leadership (1910-1920). The lighthouse took on additional responsibilities for coastal surveillance, with keepers maintaining watch for suspicious vessels while continuing their regular duties. Russell developed a coded signal system for communicating with naval vessels, and his careful organisation of blackout procedures helped maintain maritime safety while meeting wartime security requirements.

Fred Warren’s time as keeper (1927-1932) saw the most significant technological change in the lighthouse’s history – its electrification. Warren oversaw this complex transition, ensuring the keepers mastered the new electrical systems while maintaining their proficiency with the traditional equipment as a backup. His detailed documentation of the conversion process provides valuable insights into this pivotal period of lighthouse modernization.

James York’s wartime tenure (1934-1947) proved particularly challenging. World War II brought the threat of enemy action to Australian waters, and York coordinated closely with military authorities to maintain the lighthouse’s crucial navigation service while adhering to strict security protocols. His quick thinking during the SS Nimbin mining incident helped save numerous lives, earning him official commendation.

The post-war period under Henry Williams (1947-1960) saw the gradual introduction of automated systems, though the importance of human oversight remained paramount. Williams focused on preserving traditional lighthouse knowledge while adapting to new technologies, creating comprehensive training materials that would prove valuable for future keepers.

The final traditional keeper, Richard Chandler (1960-1972), guided the station through its transition to full automation. Recognising the historical significance of this change, he meticulously documented traditional practices and collected artifacts that would later form the basis of the lighthouse museum collection.

When automation finally came in 1972, it marked the end of an era spanning 91 years of continuous manned operation. The legacy of Barrenjoey’s keepers lives on not just in the continued operation of the light, but in the preserved cottages, detailed historical records, and the many technical innovations they pioneered. Their story stands as a testament to the dedication of those who devoted their lives to ensuring others’ safety at sea, often at great personal sacrifice.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

The waters surrounding Barrenjoey Head have witnessed a succession of maritime disasters starting from the earliest years of the colony when a variety on smaller ship transported produce and passengers from Sydney to the settlements along the Hawkesbury river. The discovery of coal in Newcastle significantly added to the marine traffic passing Barrenjoey as coal was transported from the Hunter region to Sydney, and this increased traffic resulted in a number of collisions, men overboard and shipwrecks along the central coast, including in the waters of Broken Bay. These waters, where the powerful currents of the Hawkesbury, Pittwater and Brisbane Waters meet the open ocean have claimed many vessels ranging from tiny fishing boats to ocean-going steamers, each tragedy contributing to the eventual establishment and ongoing importance of the lighthouse.

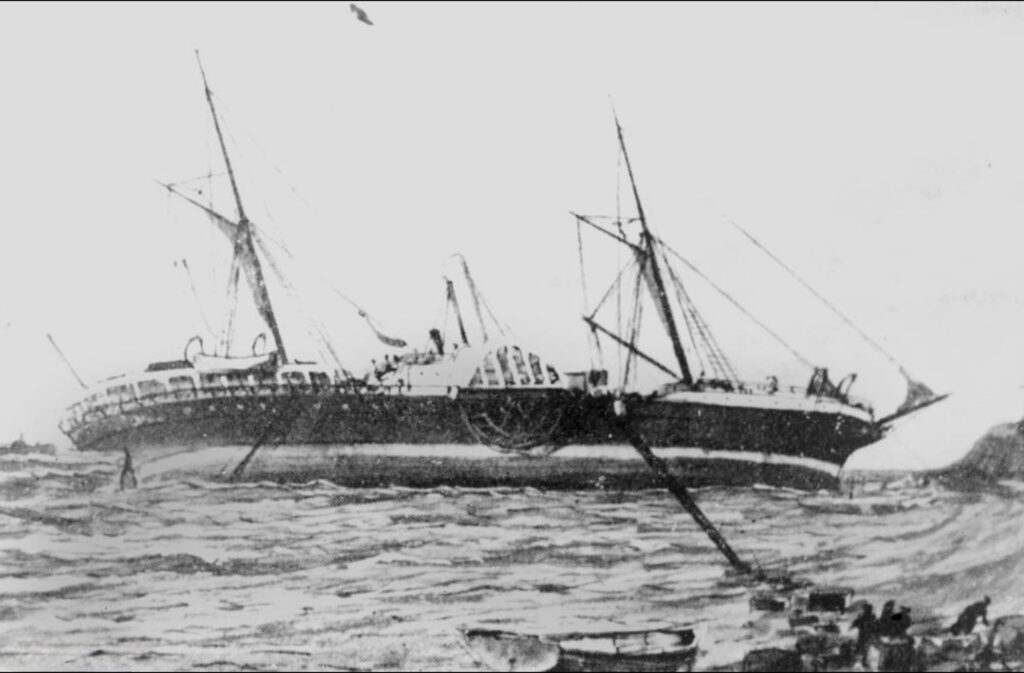

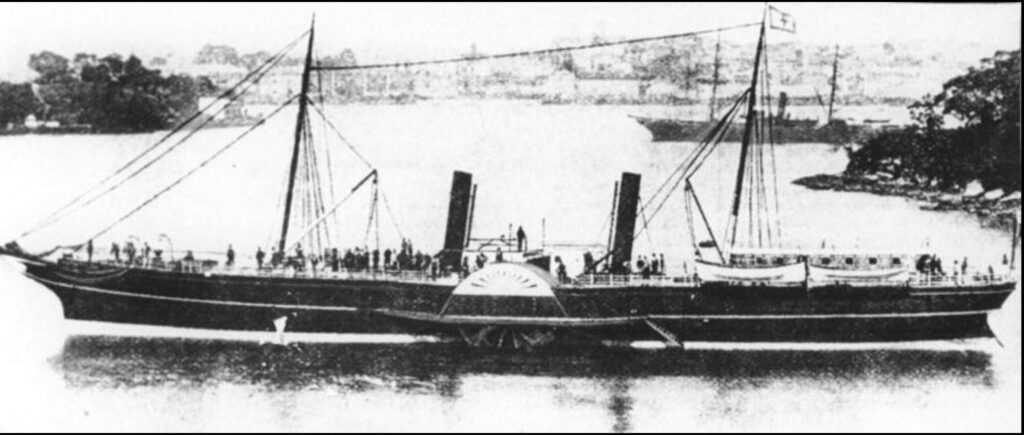

There was a serious incident on 20th January, 1881 when the SS Collaroy travelling north from Sydney in thick fog and mistook the Long Reef headland to be Barrenjoey and turned to Port in an effort to find shelter in Broken Bay only to run up on the beach that now bears its name. Fortunately no lives were lost and the ship was repaired and refloated but at the subsequent enquiry it became obvious that if the Barrenjoey light, which was under construction at the time, had been operational this incident would have been avoided.

Even after the lighthouse’s construction, the sea continued to claim its toll and ironically some of the worst disasters occured after the lighthouse was operational, and no doubt many more that were averted because of the existence of the light and the vigilance of the Keepers.

The Caledonian incident of 1882 proved to be the first major test of the new lighthouse and its keepers. The barque, caught in a severe storm, found itself driven towards the headland despite the warning beam. Keeper Isaac Banks and his assistants witnessed the unfolding drama and quickly organized a rescue operation. Using the newly installed rocket apparatus, they managed to establish a line to the stricken vessel. Over several harrowing hours, all crew members were safely brought ashore – a testament to the keeper’s courage and the value of the lighthouse station’s rescue equipment.

The 1890s brought a series of wrecks that tested the lighthouse community. The most deadly of these was the loss of the coastal steamer Maitland.

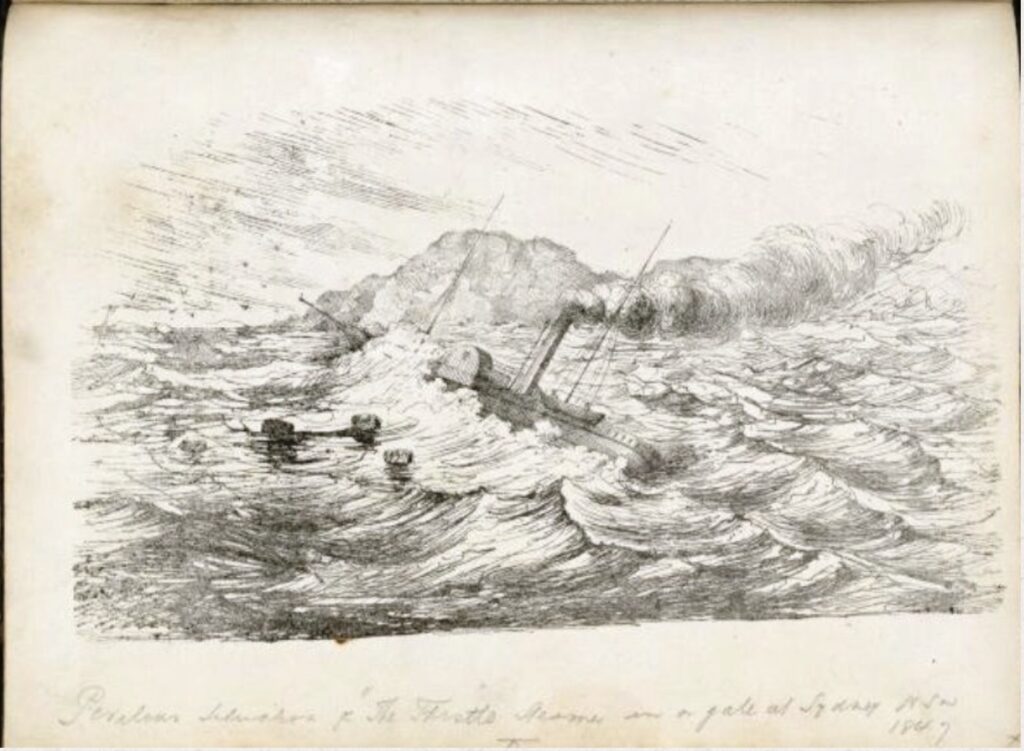

The Maitland was a regular trader along the east coast and Captain Skinner was experienced and familiar with how quickly a storm could develop to make the trip perilous. It left Sydney at 11pm on May 5, 1898, with the view of arriving in Newcastle by 9am the following morning. The ship encountered high seas and clipped the reef at Long Reef causing damage to a sponson and the hull and the ship was unstable and was taking in water. Captain Skinner decided to make a break for the safety of Broken Bay using the lighthouse at Barrenjoey as a marker to aim for. However, the ship’s engine room was swamped and the fires for the steam engine were put out. Powerless, the ship drifted past the entrance to Broken Bay and was heading towards what was previously called Boat Harbour (now Maitland Bay). Captain Skinner assembled everybody and instructed them “to prepare themselves for what was to come” and in the pre-dawn light the Maitland found itself crashing upon a rock shelf at Bouddi Point. The ship was split into two pieces with the bow of the ship breaking off and sinking within minutes. Crew and passengers in this section of the ship were trapped and drowned. The stern of the ship was washed on top of the rock shelf with the remaining passengers and crew being saved by rescuers including George Mulhall Jr. who had witnessed the drama unfolding from the lighthouse and alerted authorities before crossing the bay to join the rescue effort. Of the 63 on board 29 were killed the incident and the horror of the disaster was compounded by the fact that many victims were found washed up on the nearby beaches in the days that followed.

The storm, which came to be called the Maitland Gale, caused havoc along the coast with a number of other ships being wrecked and people lost and to this day is regarded as one of the most severe storms to have ever impacted the NSW coast and led to improvements in storm warning protocols and rescue equipment.

Footnote: One of the survivors was a baby, Daisy Hammond, who lived to the age of 90, dying in 1988. As were her wishes her ashes were scattered at the wreck site.

Sadly not all tragedies were at sea. As reported in the Sydney Herald on 15th December, 1914 “the body of Frederick Peters, aged sixty years, one of the light-keepers at the Barranjoey Lighthouse was washed up on the rocks at Stokes Point in Pittwater on Saturday afternoon. Peters was last seen alive on Wednesday morning when he left in a sailing boat for Newport. The same afternoon the boat was found on the beach near that place, and a search was then instituted for Peters, with the result stated”.

World War II brought new dangers to these waters, as demonstrated by the tragic loss of the SS Nimbin in 1940. The vessel was proceeding north when it struck a German mine laid by a naval raider off Barrenjoey Head. The explosion was so powerful it was felt at the lighthouse, where keeper James York was on duty. York immediately raised the alarm and coordinated rescue efforts, but the ship sank within minutes. Seven crew members lost their lives, while forty-two were saved through the combined efforts of the lighthouse staff and local fishing boats. The incident led to increased coastal patrols and the establishment of new defensive measures around Broken Bay.

The post-war period saw changing patterns in maritime incidents. The fishing vessel Dawn Spray was lost in 1965 during a fierce electrical storm, while the yacht Waitangi foundered in 1974 during an unexpected southerly buster. In each case, the lighthouse played a crucial role in coordinating rescue efforts and guiding emergency vessels to the scene.

Modern times have brought their own challenges. The 1980s saw several incidents involving pleasure craft, as recreational boating in the area increased. While improvements in navigation technology and safety equipment have reduced the frequency of major disasters, the waters around Barrenjoey Head continue to demand respect. Recent incidents include the grounding of the yacht Symphony in 2010 and the dramatic rescue of the fishing trawler Northern Challenger during the devastating storms of 2016.

The lighthouse continues to play a vital role in preventing maritime disasters, its beam now supplemented by modern navigation aids but still serving as a crucial backup and visible reminder of the need for vigilance at sea. Each incident in these waters has contributed to improvements in maritime safety, from enhanced warning systems to better rescue capabilities, creating a legacy of learning from tragedy that continues to save lives today.

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many ancient landmarks that stand at the intersection of land and sea Barrenjoey harbors a rich collection of mysteries, unexplained phenomena, and enduring legends. These stories span thousands of years from Indigenous Dreamtime tales to modern inexplicable occurrences, each adding another layer to the headland’s mystique.

The most persistent and well-documented mystery centres around the tragic figure of George Mulhall Senior, the keeper struck by lightning in 1885. In the decades since his death, numerous keepers, their families, and visitors have reported unexplained phenomena seemingly connected to this devastating event. The most frequent accounts describe the sound of footsteps climbing the tower stairs late at night, particularly during electrical storms. Multiple keepers have documented instances where the lighthouse door was found inexplicably open during their morning rounds, despite having been securely locked the night before.

Herbert Phillips, keeper from 1924 to 1935, maintained a separate journal documenting unusual occurrences at the station. His most intriguing entries describe instances where the massive Fresnel lens would be found spotlessly clean in the morning, though no one had performed the daily cleaning ritual. On several occasions, Phillips reported hearing the distinctive sound of the lens cleaning tools being used in the lantern room, only to find the room empty upon investigation.

The Indigenous history of the headland adds another dimension to its mysteries. Garigal elders speak of Barrenjoey as a place where the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds grows thin during certain astronomical alignments. Their traditions tell of ancient ceremonies conducted on the headland to communicate with spiritual beings, particularly during the whale migration season. Modern visitors have reported unusual atmospheric phenomena during these same seasonal periods, describing unexplained lights and strange mists that seem to defy natural weather patterns.

World War II brought its own category of unexplained events. Keeper James York’s wartime logs contain carefully worded references to mysterious lights seen offshore, often in areas where no vessels should have been present during blackout conditions. Some of these incidents coincided with documented Japanese submarine activity, but others remain unexplained even after the declassification of military records. York’s successor, Henry Williams, continued to document similar phenomena well into the 1950s.

The lighthouse structure itself holds several architectural mysteries. During renovation work in the 1960s, workers discovered a sealed room that didn’t appear on any original plans. Within this space, they found a collection of ships’ logs dating from the 1850s, well before the lighthouse’s construction. More intriguingly, some of these logs contained references to lights seen on the headland decades before any official navigation aid was established there.

One of the most enigmatic features of Barrenjoey’s mysteries involves the phenomenon known as the “Watchman’s Light.” First documented in keeper William Johnson’s logs in 1905, this manifestation appears as a small, bluish light that moves along the pathway between the keeper’s cottages and the tower. Multiple witnesses have described the light as having an intelligent quality, sometimes appearing to guide people who have lost their way on the headland during foggy conditions.

The keeper’s cottages have generated their own collection of unexplained occurrences. Former residents speak of inexplicable cold spots that persist even during summer heatwaves, particularly in the northern cottage where George Mulhall Sr. once lived. Children of keeper families often reported hearing their names called by unseen voices, while several wives documented instances of objects being mysteriously moved or returned to their proper places.

Perhaps the most scientifically intriguing phenomena involve the lighthouse’s electrical systems. Since its electrification in 1932, technicians have documented numerous instances of inexplicable equipment behaviour. During electrical storms, the backup systems often activate without any detectable power failure, while sophisticated modern monitoring equipment occasionally records power draws from circuits that should be dormant.

The 1970s brought a new wave of mysterious incidents during the lighthouse’s automation process. Workers installing the automated systems reported tools disappearing only to be found in unlikely locations, often accompanied by inexplicable cold spots and the smell of kerosene – the fuel that had powered the light for its first fifty years. Several technicians independently documented their equipment behaving erratically, particularly in the room where the original clockwork mechanism had been housed.

More recent years have seen the emergence of unusual photographic phenomena. Visitors often report camera malfunctions at specific locations around the site, while those photos that do succeed frequently show unexplained light anomalies. Professional photographers have captured images of what appears to be a figure in period keeper’s clothing within the tower, visible through the windows but vanishing upon investigation.

The Garigal people offer perhaps the most profound perspective on these mysteries. Their traditional knowledge suggests that many of these occurrences are natural manifestations of the headland’s role as a boundary place – a location where different realms of existence intersect. This understanding provides a framework for interpreting the unexplained events that continue to occur at Barrenjoey.

Modern scientific investigators have attempted to explain some of these phenomena through the study of electromagnetic fields, geological features, and atmospheric conditions unique to the headland. While some incidents have found rational explanations through these investigations, others remain mysteriously resistant to scientific analysis. Regular monitoring of environmental conditions continues to provide data that sometimes raises more questions than it answers.

These mysteries contribute significantly to Barrenjoey’s cultural heritage, attracting researchers, paranormal investigators, and curious visitors from around the world. Whether viewed through the lens of scientific inquiry, spiritual significance, or historical intrigue, these unexplained phenomena continue to fascinate visitors and researchers alike, ensuring that Barrenjoey Lighthouse remains not just a crucial navigation aid but also a place of enduring mystery.

Interesting Facts:

Architectural Distinctions:

- One of only two NSW lighthouses built in the “Australian Fortress” style characterised by its unpainted sandstone construction

- The lighthouse complex includes the only surviving example of a kerosene store built in the 1880s

- Features unique curved sandstone window reveals, a signature element of James Barnet’s design

- The site contains intact examples of early colonial stone cutting and construction techniques

Operational Records:

- Maintained continuous operation through both World Wars, serving as a coastal observation post

- Holds one of the longest continuous meteorological records in NSW, spanning from 1881 to 1972

- The original Chance Brothers lens remains in active service, making it one of the oldest operational lighthouse lenses in Australia

- Documented over 180 ship movements during its busiest recorded day in 1902

Engineering Achievements:

- Innovative use of a flying fox system during construction, later adopted at other lighthouse sites

- Original rainwater collection system capable of supporting three families year-round

- Unique foundation design incorporating natural rock formations

- First NSW lighthouse to implement specialized ventilation systems in its kerosene store

Current Status:

Today, Barrenjoey Lighthouse continues its vital role in maritime safety while serving as a significant heritage site. The lighthouse was automated in 1972, and its operation is now managed by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). The site is maintained by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service as part of Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park.

The lighthouse precinct has been carefully preserved and is listed on the State Heritage Register. Regular guided tours allow visitors to explore the tower and keeper’s cottages, providing insights into lighthouse heritage and operation. Recent years have seen increased recognition of the site’s Indigenous heritage, with ongoing consultation with Garigal representatives regarding the interpretation and preservation of cultural values.

The lighthouse stands as both a functional navigation aid and a significant historical landmark, attracting thousands of visitors annually who climb the steep track to experience this important piece of maritime heritage. Its continuing operation, using a blend of historic and modern technology, represents the successful adaptation of heritage infrastructure to contemporary needs while preserving its historical significance.

A Personal Note:

Barrenjoey is where it all began for me. From an early age I use to spend virtually ever school holiday staying with friends at Great Mackerel Beach on the western shore of Pittwater, with a direct line of sight to Barrenjoey. Each night when I went to bed I would watch the flashing light and think of all the things it must have “seen” over the years. Every now and then we’d visit the lighthouse and say hello to Pat, the hermit lady who lived there with her cats, and to Jarvis the caretaker. I’m sure this is where I first developed what has become a lifelong fascination with lighthouses, and all they represent.

Wonderful report Mike and so close to home

I’m extremely inspired together with your writing skills and also with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid topic or did you modify it your self? Either way stay up the excellent high quality writing, it is rare to see a nice blog like this one nowadays. !