Location:

Norah Head Lighthouse stands prominently on a rugged headland between Tuggerah Lake and Budgewoi Lake on the Central Coast of New South Wales, mid way between the major ports of Sydney and Newcastle. The lighthouse rises 27.5 meters above ground level, with its focal plane at 46 meters above sea level. This strategic position allows the light to be visible for up to 20 nautical miles, serving as a crucial navigational aid for vessels traveling along the NSW coast between Sydney and Newcastle.

The headland itself rises dramatically from the ocean, forming a natural promontory that has guided maritime traffic since pre-colonial times. The site’s geology consists of exposed Narrabeen sandstone formations that have been shaped by millions of years of ocean forces, creating a complex system of reefs and platforms extending up to 1.6 kilometers offshore. These underwater hazards, combined with strong coastal currents and unpredictable weather patterns, made this stretch of coastline particularly treacherous for shipping before the lighthouse’s construction.

The site experiences dramatic weather conditions, particularly during southerly busters and east coast low pressure systems. Wind speeds can exceed 100 km/h during severe storms, while the elevated position exposes the lighthouse to constant salt spray and extreme temperature variations. The lighthouse’s location at the convergence of warm East Australian Current waters with cooler southern flows creates unique meteorological conditions that can rapidly generate severe weather events.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 33° 16′ 49″ S Long: 151° 34′ 51″ E

First Lit: November 15, 1903 (Automated 1984, demanned 19XX)

Tower height: 27 meters

Focal Height: 46m above MSL (white), 44m (green) & 39m red)

Original Lens: Second Order Chance Brothers Dioptric

Intensity: 1,000,000 candela

Range: 30 nautical miles

Characteristic: One White flash every 15 seconds [Fl.W 15s, FR to northeast, FG southwest]

Indigenous History:

The area around Norah Head holds profound significance for the Darkinjung people, who have maintained an unbroken connection to this country for tens of thousands of years. Archaeological evidence, including extensive middens, tool-making sites, rock carvings and ceremonial grounds demonstrate continuous occupation spanning millennia.

The headland features prominently in Darkinjung Dreaming stories, particularly those relating to the creation of the coastal landscape and the relationship between land and sea. Traditional stories speak of the headland as a significant gathering place during whale migrations, with the elevated position allowing people to track the movement of whales and coordinate hunting activities.

The surrounding marine environment provided abundant food with the Darkinjung people developing sophisticated fishing techniques specific to this location. Their knowledge encompassed understanding of tidal patterns, fish migrations and seasonal changes that enabled sustainable fishing practices. The rock platforms around the headland and nearby lakes were particularly important for gathering a range of seafoods.

Darkinjung elders maintained detailed knowledge of weather patterns and ocean conditions using the headland as a vital observation point. This traditional knowledge included understanding the relationship between cloud formations, wind patterns, and approaching weather systems – information that would later prove valuable to early lighthouse keepers.

The cultural significance of the area extends beyond sustenance with the headland playing a role in ceremony and education. Rock engravings and other cultural sites in the vicinity demonstrate the spiritual importance of this landscape to Darkinjung people though many of these sites were unfortunately damaged or destroyed during colonial development.

Colonial History:

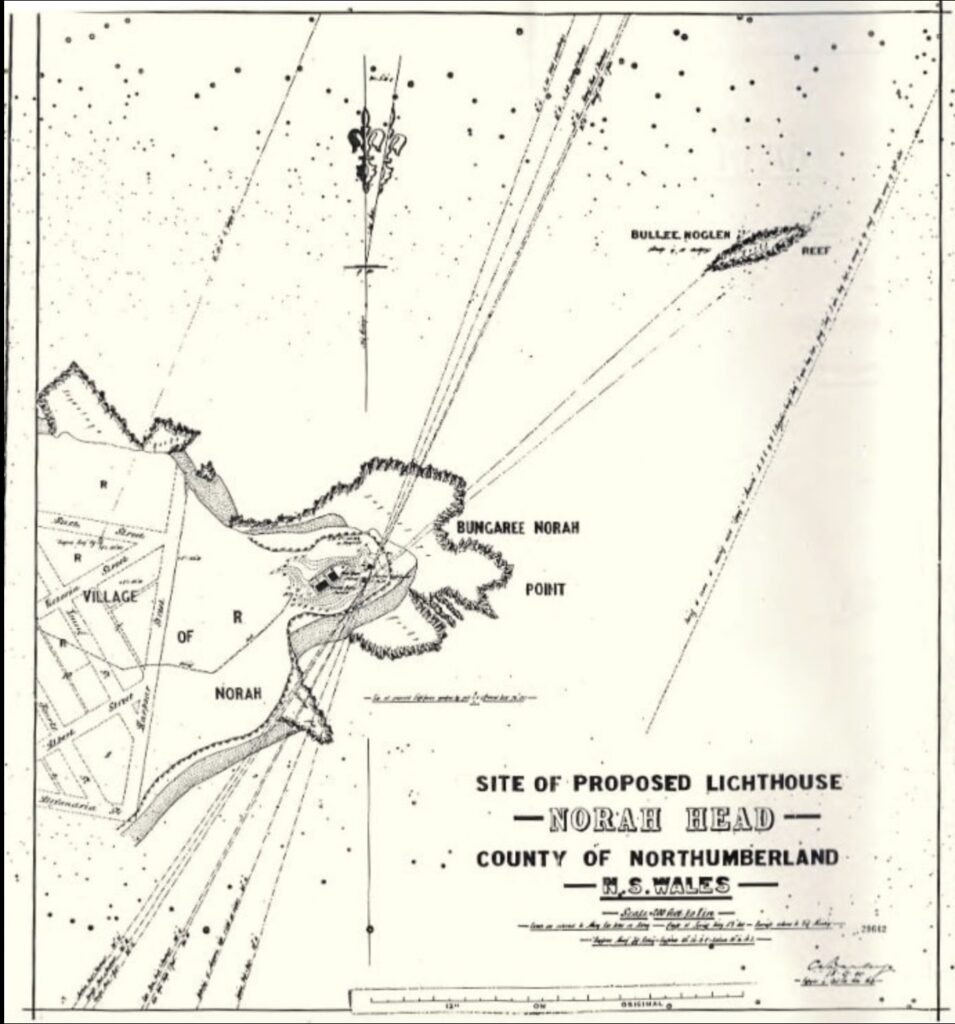

European maritime contact with the Norah Head region began in the early 1800s, though the area’s treacherous coastline quickly gained notoriety among colonial mariners. The first detailed charts of the area were produced during Lieutenant James Grants coastal survey in 1801, where he noted the distinctive headland and its dangerous offshore reefs.

The name “Bungaree Norah” emerged during this period, combining references to Bungaree, an Aboriginal elder who assisted early colonial authorities, and the vessel “Norah Creina.” Some historical records suggest alternative origins for the “Norah” portion of the name, including possible connections to Honora Jordan, wife of a local settler, though the maritime connection is generally considered more likely.

By the 1820s, regular coastal traffic was passing the headland as vessels transported cedar, coal, and other resources between Sydney and Newcastle. The increasing maritime traffic led to numerous incidents with ships frequently running afoul of the offshore reefs, particularly during poor weather or nighttime navigation.

The first formal proposal for a lighthouse at Norah Head came in 1861 though it would take four decades of lobbying and several major maritime disasters before construction was approved. The delay was partly due to competing demands for lighthouse construction along the NSW coast, and partly due to debates over the most effective locations for new lights between Sydney and Newcastle.

The growth of local settlements and industries in the late 1800s, particularly around Tuggerah Lake and Lake Macquarie, added weight to arguments for a lighthouse. Local fishing fleets, timber getters, and coastal traders all supported the campaign for improved navigation aids in the area.

The Lighthouse:

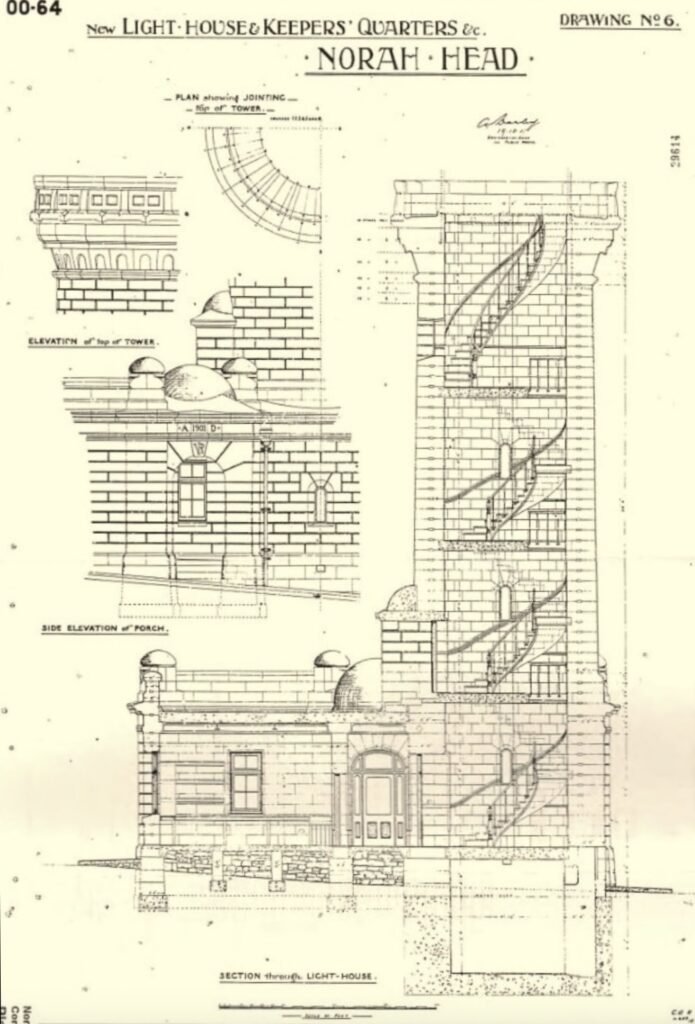

The decision to construct a lighthouse at Norah Head was finally made in 1901, following a comprehensive review of maritime safety needs along the NSW coast. The project was approved under the supervision of Charles Assinder Harding from the Colonial Architect’s Office, who would pioneer several innovative construction techniques during the build.

The lighthouse’s design represented a significant departure from traditional Australian lighthouse construction methods. Instead of the usual sandstone construction Harding opted for precast concrete blocks making Norah Head the third Australian lighthouses to use this building technique. This decision was influenced by both economic considerations and the need for rapid construction as shipping traffic in the area had increased significantly by the turn of the century.

Construction began in March 1901 with the establishment of a concrete casting yard on site. Local materials were used wherever possible including desalinated sand from nearby beaches and aggregate from local quarries. The concrete blocks were cast in specially designed molds, allowing for precise dimensional control and the creation of the tower’s graceful taper.

The construction process presented unique challenges, particularly in transporting materials to the elevated site. A temporary tramway was constructed from the nearby bay to facilitate the movement of heavy equipment and materials. Local laborers were employed alongside skilled craftsmen creating valuable employment opportunities for the growing coastal communities.

The Buildings:

Norah Head Lighthouse’s tower rises 27 meters from its base to the top of the lantern room, with walls tapering from 1.37 meters thick at the base to 0.61 meters at the top. The innovative use of precast concrete blocks allowed for precise construction while providing excellent durability in the harsh marine environment. The tower’s elegant proportions and architectural details reflect the Victorian architectural influences of the period.

The structural design incorporates several sophisticated features including:

- A double wall construction system with ventilation cavity to regulate temperature and prevent condensation,

- Carefully calculated load-bearing capabilities to support the massive optical apparatus,

- Integral water collection and drainage systems,

- Specially designed foundation system to ensure stability on the headland site.

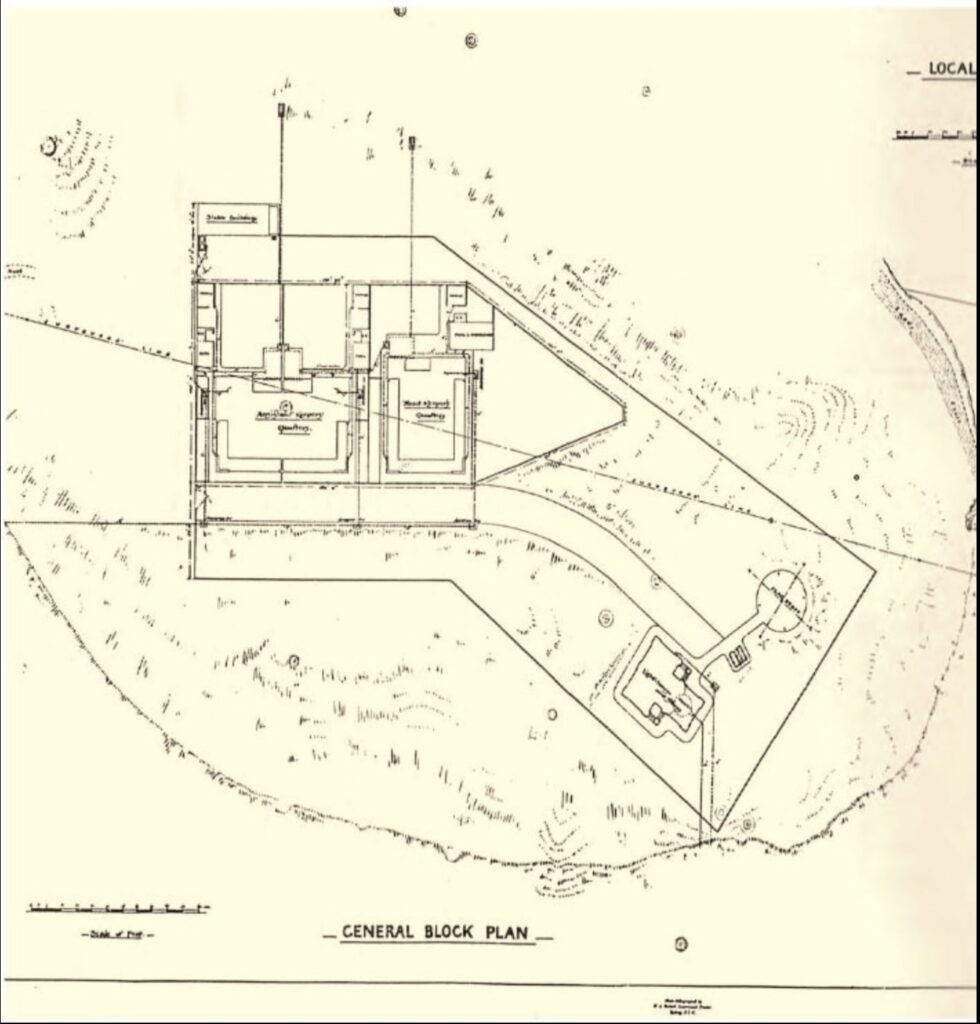

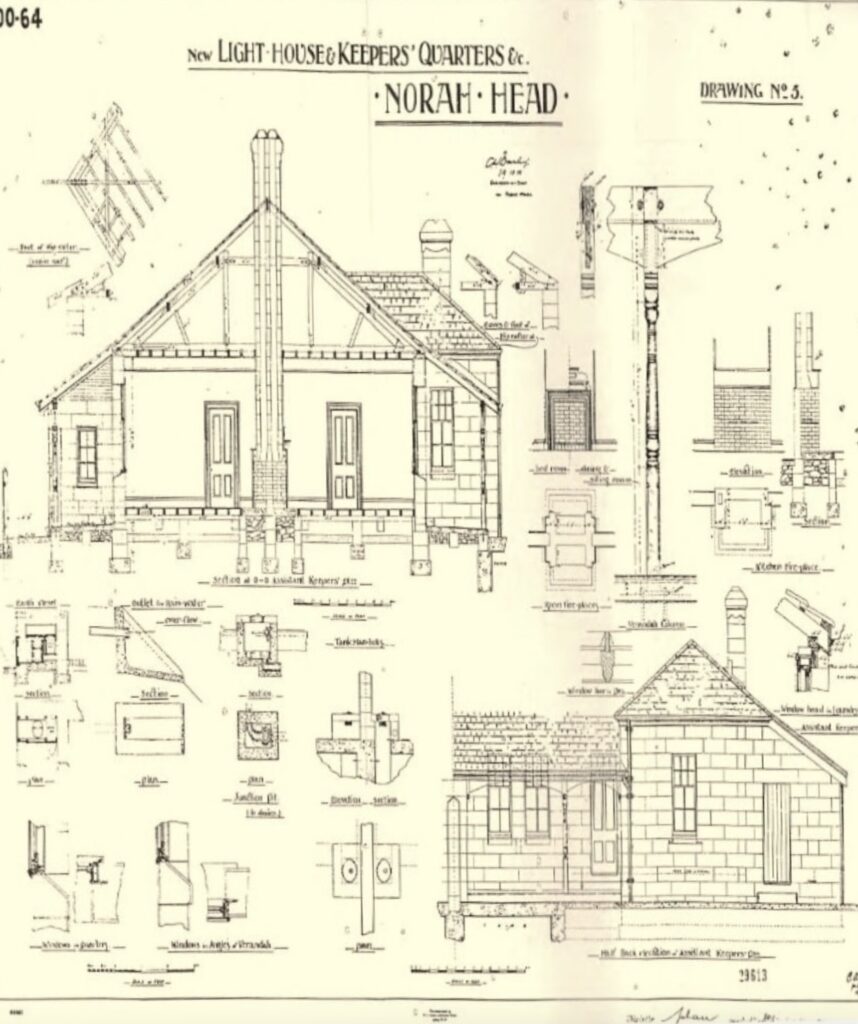

The lighthouse complex includes three keeper’s cottages, built in Federation style architecture with local materials. The principal keeper’s cottage, larger and more elaborate than the assistants’ quarters, features detailed architectural elements including decorative verandah posts, intricate woodwork, and custom joinery. All cottages were designed to provide comfortable accommodation while withstanding severe coastal weather conditions.

Additional structures within the complex include:

- The original signal house, used for communications with passing vessels

- Workshop and store buildings for maintenance equipment and supplies

- Fuel store for the kerosene vapor lighting system

- Generator house (added during electrification)

- Water collection and storage systems

- Stables (later converted to garage space)

The entire precinct was carefully planned to function as a self-contained community reflecting the isolated nature of lighthouse operations in the early 20th century. Gardens were established around the cottages providing both food production and aesthetic value while pathways and fencing were constructed to define public and private spaces within the complex.

Technical Details:

The original lighting apparatus represented the pinnacle of maritime illumination technology for its era. The Second Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens consisted of precision-ground glass prisms arranged in a clamshell pattern around a central light source. The entire optical assembly rotated on a mercury bath pedestal providing nearly frictionless operation and precise flash characteristics.

When first lit on November 15, 1903 the optical apparatus was carefully designed to produce a distinctive pattern of two flashes every 15 seconds distinguishing it from other lights along the coast. The original light source used vaporized kerosene, providing a light intensity of approximately 100,000 candelas.

Key components of the original system included: Second Order Chance Brothers lens (1903), Chance Brothers mercury bath pedestal, clockwork rotation mechanism, five-wick kerosene vapor burner, hand-wound weight drive system and auxiliary standby equipment.

The electrification project of 1961 brought significant changes to the technical systems while preserving the historic optical apparatus. Major upgrades included: installation of electric drive motors for lens rotation, conversion to electric light source, installation of backup power systems, automated lamp changers and modern monitoring and control systems.

Current technical specifications: Light source: 120V LED lamp, mains electricity with battery backup, intensity: 700,000 candelas, range: 20 nautical miles, characteristic: Group flashing (2) every 15 seconds, rotation: Electric drive with electronic monitoring, backup systems: Diesel generator and duplicate lamp array, automated monitoring and control systems and remote operation capability.

Keepers of the Light:

For over 80 years, dedicated lighthouse keepers maintained the vital service at Norah Head. Each keeper and their family contributed to the rich tapestry of lighthouse history, creating a unique community atop the windswept headland.

Edwin Casley Thoroughgood (1903-1921); the first Principal Keeper, established the foundation for lighthouse operations. His meticulous attention to detail and comprehensive understanding of maritime needs helped establish Norah Head as a crucial navigational aid. Thoroughgood developed detailed procedures for maintaining the complex optical apparatus and managing the station that would guide future generations of keepers.

Each keeper’s shift involved constant vigilance, with additional duties during severe weather or maritime emergencies. The isolation of the station meant keepers and their families needed to be largely self-sufficient, maintaining gardens, managing water supplies, and handling basic repairs.

Other Notable Head Keepers included:

Albert Smith (1921-1935), implemented early modernization initiatives while maintaining traditional practices. His wife Sarah established a small school for the keepers’ children, creating an important educational hub for the isolated community. Smith’s detailed weather observations contributed significantly to understanding local meteorological patterns.

Richard Thompson (1935-1949), guided operations through World War II, when the lighthouse played a crucial role in coastal defense. His wartime logs detail the challenges of maintaining the light while adhering to blackout regulations and security protocols. Thompson developed innovative systems for rapid light reduction during air raid warnings.

John McKinnon (1949-1961), oversaw the transition to electric power, requiring keepers to develop new technical skills while maintaining traditional practices. His detailed documentation of the electrification process proved invaluable for other stations undergoing similar modernization. McKinnon’s wife Eleanor served as an unofficial historian, preserving stories and photographs of lighthouse life.

Herbert Porteous (1961-1973), managed the introduction of automated systems while ensuring the preservation of traditional lighthouse knowledge. His careful records of both old and new practices helped bridge the gap between manual and automated operations. Porteous was known for mentoring younger keepers, passing on crucial skills and understanding.

Malcolm Ridges (1973-1984), the final Head Keeper, guided the station through its transition to full automation. He ensured that important aspects of lighthouse heritage were documented before the end of manned operations. Ridges worked closely with maritime authorities to develop protocols for the automated system’s maintenance and monitoring.

Assistant Keepers who made notable contributions included:

- James Wilson (1903-1915) – Developed innovative lens cleaning techniques

- Thomas Barrett (1915-1932) – Known for rescue work during storms

- William Henderson (1932-1947) – Wartime observation specialist

- Robert MacPherson (1947-1965) – Technical innovations during electrification

- Peter Collins (1965-1980) – Documentation of traditional practices

Each keeper brought unique skills and experiences to the role, contributing to the station’s evolution while maintaining its essential function as a navigational aid. Their collective dedication ensured the light’s constant operation through war, technological change, and severe weather events.

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

Despite the lighthouse’s presence, the waters around Norah Head have witnessed numerous maritime disasters, each contributing to the evolution of maritime safety practices and local rescue capabilities.

SS Nerong Disaster (1904): Just months after the lighthouse began operation, the SS Nerong foundered on rocks near the headland during a fierce storm. Keeper Thoroughgood’s log provides a vivid account of the disaster: “At 0300 hours, observed vessel in distress approximately one mile offshore. Heavy seas breaking over her bow. Immediately notified local fishing boats and prepared rescue equipment. Conditions extremely hazardous with wind gusting to 60 knots.” Through coordinated efforts between lighthouse staff and local fishermen, all crew members were saved, though the vessel was a total loss. The incident led to improved protocols for coordinating rescue efforts between the lighthouse and local maritime community.

SS Wallarah (1914): Was one of a fleet of colliers that carried coal from Newcastle to Sydney, these ships became known as the “60 milers“, as this was the distance between the two ports. The coal was loaded at Catherine Hill Bay, which lies between Norah Head and Nobby’s, and is a particularly treacherous part of the coast with many offshore reefs, strong currents and large waves. Whilst not a long journey it was notoriously dangerous and the Wallarah was the first of a number of “60 milers” to come to grief on this stretch of coast and the keepers at Norah Head were involved in many incidents, near misses and rescues over the next 60 years until the “60 milers” were replaced by railways.

The Rose Tragedy (1932): The coastal trader Rose struck the reef system in heavy seas, leading to one of the most dramatic rescue operations in the station’s history. Keeper Smith coordinated with local boats while maintaining communication with the stranded vessel through signal flags. The rescue highlighted the need for improved charts of the offshore reef systems, leading to a detailed maritime survey of the area.

Wartime Incidents: During World War II, the waters off Norah Head saw increased military activity and several significant incidents:

- June 1942 – Suspected submarine attack on merchant vessel

- August 1943 – Naval vessel collision during blackout conditions

- March 1944 – Aircraft ditching witnessed by keeper staff

- Multiple reports of suspicious vessels and activities

Keeper Thompson maintained detailed records of wartime incidents while coordinating with naval authorities. The lighthouse played a crucial role in directing rescue operations for several maritime emergencies during this period.

MV Wickham Tragedy (1951): The collision of the MV Wickham with submerged rocks highlighted continuing dangers despite modern navigation aids. Keeper McKinnon’s log describes the incident: “Vessel attempted to seek shelter from southerly buster. Despite warning signals, struck northern reef. Conditions prevented immediate rescue attempt. Maintained visual contact throughout night while coordinating with emergency services.” The incident led to revised protocols for vessels seeking shelter during severe weather.

Other Notable Incidents:

- 1906 – Emma Mitchell: Lost during sudden squall

- 1915 – Paterson: Run aground after hitting a reef off Norah Head

- 1925 – Wanderer: Driven onto rocks despite warning signals

- 1931 – Paterson: Foundered off Norah Head

- 1938 – Sea Bird: Foundered in heavy seas

- 1956 – Northern Star: Collision with uncharted obstacle

- 1973 – Marina: Weather-related grounding

- 1982 – Kanimbla: wrecked while in transit to Newcastle

- 1988 – Eagle Wind: Navigation error in poor visibility

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many historic lighthouses, Norah Head has accumulated a rich collection of unexplained phenomena, local legends, and mysterious occurrences that have become part of its cultural heritage.

The Darkinjung Guardian: Central to Indigenous traditions is the story of a spiritual guardian that watches over the headland. Darkinjung elders speak of this presence as a protector of both the land and those who travel the waters around Norah Head. Multiple keepers reported unusual experiences that aligned with these traditional stories. These include: unexplained sounds during significant astronomical events, mysterious lights during whale migrations, strange atmospheric phenomena during ceremonial times and unexpected weather changes preceded by unusual signs. The keeper logs contain numerous references to these phenomena, with Keeper Thompson’s 1938 entry being particularly detailed: “Observed unusual atmospheric effect at dawn – a distinct figure appeared to stand atop the northern reef, visible for several minutes before dissipating. Local elders later confirmed this as a traditional sign of approaching weather change.”

The Vanishing Light: One of the most persistent mysteries involves reports of an unexplained light seen moving offshore. First documented by Keeper McKinnon in the 1950s, the phenomenon has been witnessed by multiple reliable observers including: multiple keeper families reported similar sightings, commercial fishermen documented encounters, naval vessels recorded unexpected light signals and modern maritime authorities have logged unexplained readings. These sightings share common characteristics such as: movement against prevailing currents, ability to appear and disappear rapidly, light characteristics different from known vessels and are often preceded by unusual weather conditions.

WWII Mysteries: The wartime period generated several enduring mysteries including: unexplained radio signals detected by lighthouse equipment, strange lights reported during blackout periods, unidentified submarine activity, missing military correspondence and unexplained equipment malfunctions during specific dates. Keeper Richard Thompson maintained a separate coded log of wartime anomalies, much of which remains classified. His records hint at significant naval activity that has never been fully explained in public documents.

Modern Phenomena: Even in recent years, unusual occurrences continue to be reported, these include: electronic equipment malfunctions coinciding with significant dates, unexplained temperature variations in specific areas of the tower, anomalous readings from modern navigation equipment, photographic anomalies during certain atmospheric conditions and unusual acoustic phenomena during storm events. Scientific investigations have documented several unexplained features such as: localised magnetic anomalies around the tower base, unexpected patterns in weather data, unusual marine life behavior in surrounding waters and acoustic properties that defy standard analysis.

Traditional Knowledge: Darkinjung elders maintain that many of these phenomena are natural manifestations of the headland’s spiritual significance. Their traditional knowledge provides context for understanding these occurrences including: the relationship between celestial events and earthly phenomena, the connections between whale migrations and spiritual activity, the importance of seasonal cycles in spiritual manifestations and the role of the headland in traditional ceremonies.

Interesting Facts:

Norah Head Lighthouse holds several distinctive features and historical elements that make it unique among Australian lighthouses:

Construction Innovation:

- One of the first Australian lighthouses built using precast concrete blocks instead of traditional sandstone

- The concrete blocks were manufactured on-site using local sand and aggregates

- Each block was precisely molded to create the tower’s distinctive taper

- The construction method proved so successful it influenced future lighthouse designs

Architectural Features:

- Original brass fittings throughout the tower remain intact

- The tower’s internal ventilation system was revolutionary for its time

- It features one of the few remaining original Chance Brothers first order lenses still in operation in Australia

Historical Significance:

- The lighthouse was the last significant lighthouse built in NSW during the colonial period

- It was one of the last Commonwealth lighthouses built in NSW before Federation

- The original mercury bath flotation system for the lens remains intact

- The keeper’s quarters are among the most complete and original lighthouse residences in Australia

- It was one of the last lighthouses in NSW to be automated (1984)

Operational Distinctions:

- The light’s characteristic (two flashes every 15 seconds) has remained unchanged since 1903

- The original clockwork mechanism operated continuously for over 50 years without major repairs

- The lighthouse maintained manual operation throughout both World Wars

- It was one of the few lighthouses to maintain its original optical apparatus during electrification

Natural Environment:

- The headland hosts one of the largest little penguin colonies on the NSW central coast

- The surrounding waters are a recognized whale watching location during migration seasons

- The geological formations around the lighthouse date back to the Permian period

- The area is one of the few places where the warm East Australian Current meets cooler southern waters

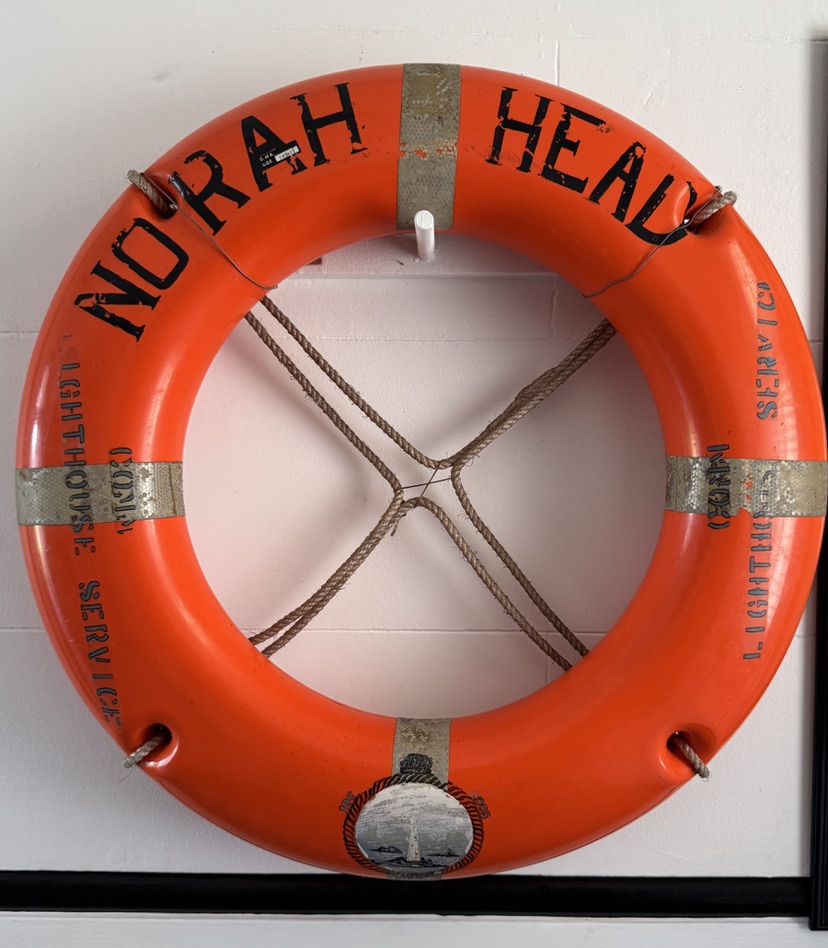

Cultural Heritage:

- The lighthouse precinct contains one of the most complete collections of lighthouse keeper artifacts in NSW

- Original furniture remains in the keeper’s quarters

- The station’s log books provide an unbroken record from 1903 to automation in 1984

- Indigenous artifact scatters near the lighthouse are some of the most significant on the Central Coast

Little-Known Facts:

- The lighthouse keeps a visitor’s book dating back to its opening in 1903

- Several Australian films and television shows have used the location for filming

- The lighthouse tower has never been struck by lightning due to its innovative protection system

- Secret tunnels were reportedly built during WWII but never officially documented

- The lighthouse was briefly considered as a site for early radio broadcasting experiments

Conservation Milestones:

- Original blueprints and construction documents survive intact

- First lighthouse in NSW to have a full archaeological survey of its grounds

- Maintains the largest collection of original lighthouse maintenance tools in Australia

- Houses a significant collection of historical photographs and documents

- Pioneered new techniques for concrete conservation in marine environments

Current Status:

Today, Norah Head Lighthouse continues its vital role in maritime safety while serving as a premier heritage tourism destination. The site represents a successful balance between preserving historical significance and adapting to modern requirements.

Operational Status includes: automated operation under AMSA supervision, regular maintenance schedule, modern backup systems, remote monitoring capability and integration with digital navigation networks.

Heritage Conservation: The site is protected under multiple heritage listings including: NSW State Heritage Register, Commonwealth Heritage List and National Trust Register

Conservation works have included: restoration of original optical apparatus, structural repairs using traditional methods, preservation of keeper’s quarters, landscape rehabilitation and documentation of historical features.

Management Structure: The Norah Head Lighthouse Reserve Land Manager, a community-based organization, oversees: site maintenance, tourism operations, heritage conservation, educational programs and community engagement.

The lighthouse stands as a testament to maritime heritage while embracing its role in modern coastal navigation. Its successful transition from manned operation to automation while maintaining historical integrity and public accessibility represents a model of heritage conservation and adaptive reuse.

Through careful management and community support, Norah Head Lighthouse remains both a vital navigation aid and a significant heritage site, preserving its important role in Australia’s maritime history while serving the needs of modern visitors and mariners.

A Personal Note:

For whatever reason I had never been to Norah Head before, nor had I heard of its lighthouse, which given its proximity to Sydney and the stature of its lighthouse and beauty of the surrounding coast and lakes was a major oversight and one that I’m glad to have remedied albeit after too many years.

I can only assume that in all my years of travelling up and down the NSW coast my rush to get to more fancied destinations further up the coast I had leapfrogged the central coast and allowed the negative reputation of The Entrance and other less attractive parts of the central coast unduly influence my attitude to the whole of the central coast.

Suffice to say that Norah Head and surrounds including Soldiers Beach and Budgewoi Lake are well worth visiting and Norah Head lighthouse is magnificent – both architecturally and in regard to its upkeep and the pride the local community display in looking after “their” lighthouse. Oh, and one other thing, there is a great fish & chip shop at Budgewoi!