Location:

Port Stephens Lighthouse, also known as Fingal Island Lighthouse lies 5km south east of Port Stephens on the mid-north coast of NSW. The lighthouse commands the eastern end of a rocky island approximately 3km offshore, strategically positioned at the entrance to Port Stephens harbor. At 38 meters above sea level, its elevated position provides exceptional visibility along the coastline,

The maritime approach to Port Stephens is characterized by strong currents and shifting sandbanks, making the lighthouse’s guidance particularly crucial during adverse weather conditions. The island’s position creates a natural breakwater for the harbor entrance, though this same feature can create challenging wind and wave patterns that mariners must negotiate. The lighthouse’s elevation ensures its beam remains visible even during heavy swells with its beam visible for up to 21 nautical miles in clear conditions.

The island’s geography tells a story of how dynamic the coastline can be. Originally a peninsula connected to the mainland by a natural sand spit, it was transformed into an island during a catastrophic storm in 1891. This dramatic geological event fundamentally altered not just the landscape but also the operational challenges of maintaining the lighthouse. The lighthouse’s exposed position places it directly in the path of the prevailing storms and powerful swells that continually test the lighthouses structural integrity and operational reliability.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 32° 44′ S Long: 152° 12′ E

First Lit: 1st May, 1862 (Automated 1973, Demanned 1991)

Tower height: 21 meters

Focal Height: 38m above MSL

Original Lens: First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens

Intensity: 407,000 candela

Range: 21 nautical miles

Characteristic: Four White flashes every 30 seconds [Fl.(4)W 30s]

Indigenous History:

The area around Port Stephens, including Fingal Island, holds deep cultural significance as part of the traditional lands of the Worimi people. For countless generations before European settlement, this coastal region served as an integral part of Worimi cultural, spiritual, and economic life. The Worimi people developed a deep knowledge systems around the area’s marine and terrestrial seasonal patterns and navigation challenges passing this expertise down through generations of oral tradition.

Archaeological evidence proves Indigenous occupation dating back thousands of years and provides insight into their fishing, hunting and cultural practices and dietary patterns and provides evidence suggesting trade networks that extended inland from this coastal hub. The high vantage point where the lighthouse now stands served as a crucial lookout point for the Worimi people, allowing them to track whale migrations, monitor weather patterns, and observe the movement of fish, birds and native animals, a knowledge that was vital for both sustenance and ceremonial purposes.

The Worimi people’s connection to this landscape extended beyond their day to days needs and the area features prominently in Dreamtime stories, with the island’s original peninsula formation playing a role in cultural narratives about land formation and ancestral beings. The surrounding waters were not just fishing grounds but sites of cultural learning, where young people were taught the intricate knowledge needed to read weather patterns, understand tidal movements and navigate safely through the challenging coastal waters.

Traditional ecological knowledge maintained by the Worimi included sophisticated understanding of marine ecosystems, including seasonal fish migrations, breeding cycles of various marine species, and sustainable harvesting practices. This knowledge extended to weather prediction through observation of cloud patterns, bird behaviour and other natural indicators – many of which would later prove valuable to European maritime operations in the area.

The transformation of the peninsula into an island in 1891 holds particular significance in Worimi oral histories, with stories suggesting that traditional knowledge had long predicted the possibility of such an event. The island’s isolation after this event created new patterns of access and use, though the cultural significance of the site remained undiminished.

Port Stephens region, the Worimi people

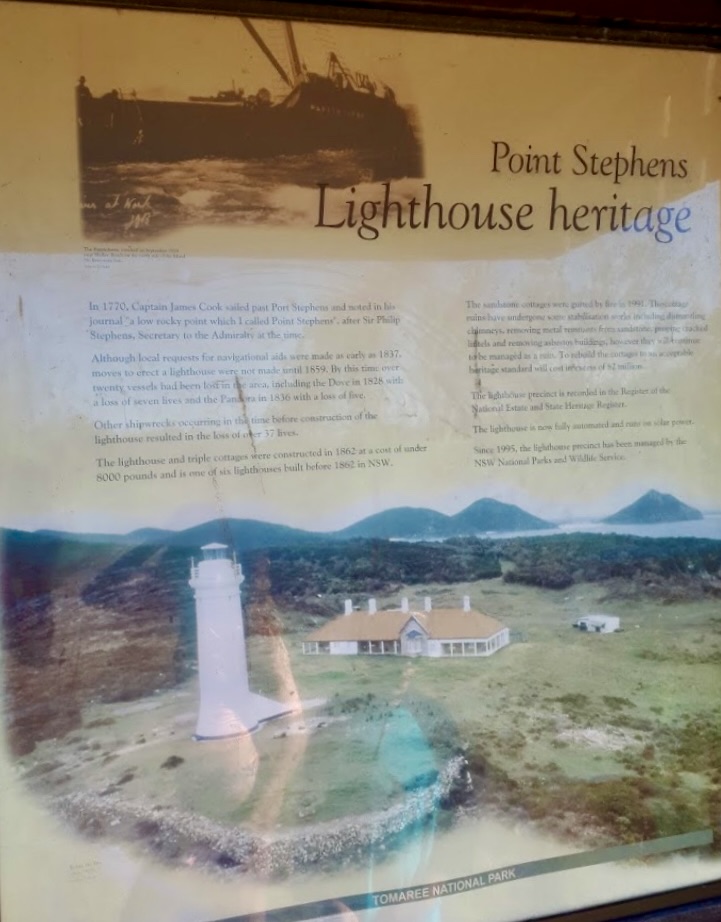

Colonial History:

The emergence of Port Stephens as a crucial maritime waypoint in the early 1800s coincided with the rapid expansion of colonial maritime activity along Australia’s eastern seaboard. The port’s natural deep-water harbor and strategic position made it increasingly important for the burgeoning timber trade, with valuable hardwoods from the surrounding forests being shipped to Sydney and beyond. The growing volume of coastal shipping, combined with the area’s treacherous underwater topography, soon highlighted the urgent need for navigation aids.

The catalyst for the lighthouse’s construction came through a series of tragic shipwrecks in the 1850s. The most notable was the loss of the merchant vessel “Dove” in 1856, which struck an uncharted reef during a night approach to the harbor. This incident, along with several other near-misses, prompted urgent petitions from maritime merchants and local settlers for improved navigation aids. The Colonial Government of New South Wales, initially reluctant due to budget constraints, was finally compelled to act after a delegation of prominent shipping companies threatened to bypass the port entirely.

The decision to build the lighthouse triggered intense debate about its precise location. Some argued for placement on the mainland, citing easier access for construction and maintenance. However, the final choice of Fingal Peninsula (as it was then) was influenced by several factors: its commanding position, the solid rocky foundation, and its ability to serve both as a harbor entrance marker and a coastal navigation aid. The selection committee, led by the Colonial Architect Alexander Dawson, conducted extensive surveys throughout 1860 before finalising the location.

The project faced significant logistical challenges from the outset. Construction materials had to be transported by sea, with a temporary jetty built to facilitate landings. Local Aboriginal knowledge proved invaluable during this phase, with Worimi people advising on safe landing spots and weather patterns. The construction team, consisting of both skilled stonemasons brought from Sydney and local labourers established a temporary settlement on the peninsula, complete with workshops and living quarters.

The colonial government’s investment in the lighthouse project represented more than just a response to maritime safety concerns – it was a statement of the colony’s growing maritime capabilities and economic ambitions. The decision to use high-quality materials and the latest lighting technology reflected a desire to establish Port Stephens as a major maritime hub along the colonial shipping routes.

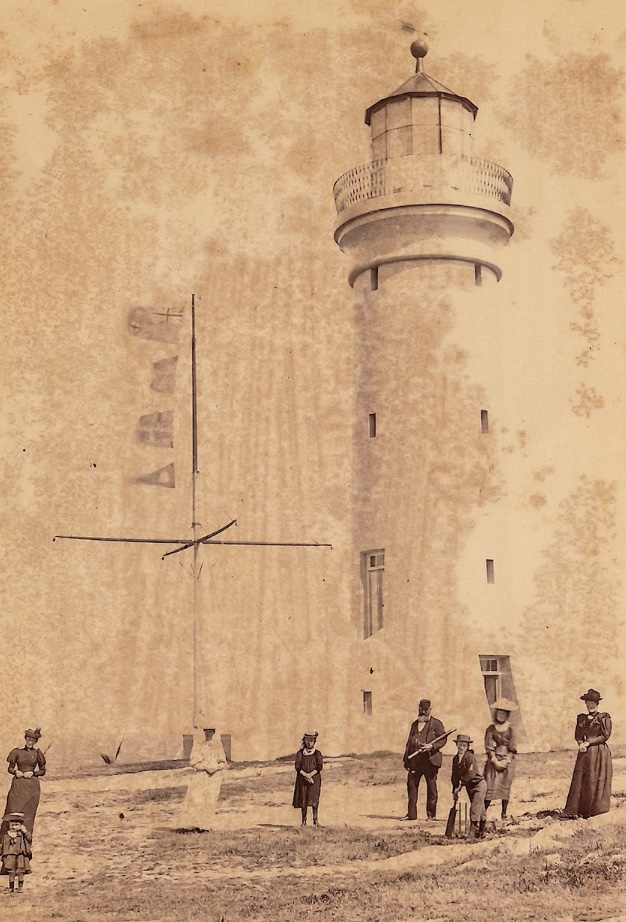

The Lighthouse:

Alexander Dawson’s design for Port Stephens Lighthouse represented a significant evolution in colonial lighthouse architecture, blending classical elements with practical innovations suited to the harsh coastal environment. Construction began in April 1861 with the challenging task of establishing proper foundations on the rocky headland. The project employed innovative construction techniques rarely seen in colonial Australia at that time, including the use of hydraulic lime mortar specially formulated to resist salt spray deterioration.

The construction process itself became a testament to colonial engineering ingenuity. A temporary railway was constructed from the landing point to the building site, utilizing a clever system of counterweights to move heavy stones up the incline. The locally quarried sandstone proved both a blessing and a challenge – while reducing transportation costs, it required specialized cutting techniques to achieve the precise angles needed for the tower’s tapering design. Master stonemason James Glover developed specific tools and techniques for working with the unusually dense local stone, methods that would later influence other lighthouse constructions along the coast.

The lighthouse’s inauguration on 1st May 1862 marked the installation of what was then the most advanced lighting technology available. The First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, manufactured in Birmingham, England, represented a significant investment by the colonial government. The lens assembly, weighing several tons, arrived in dozens of carefully packed crates and took over three weeks to assemble under the supervision of a specialist technician sent from England.

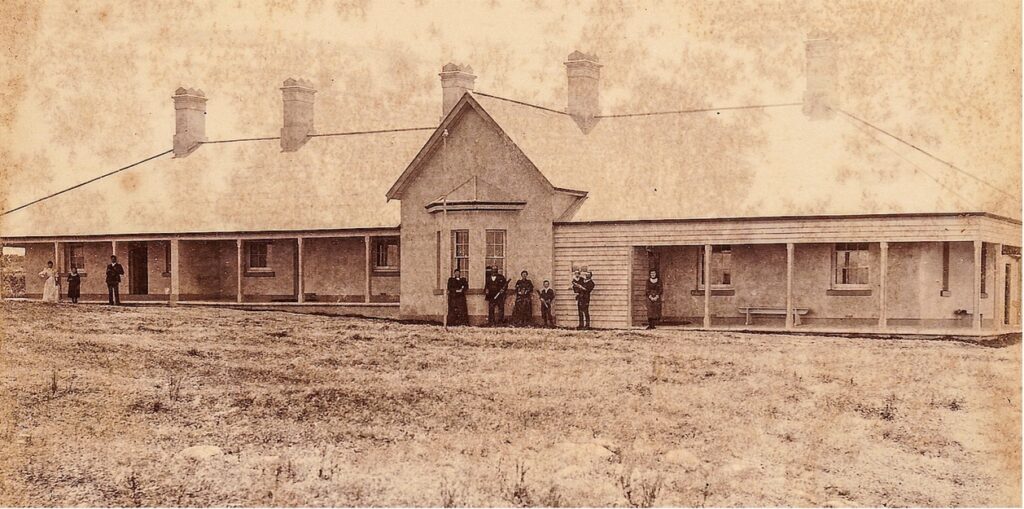

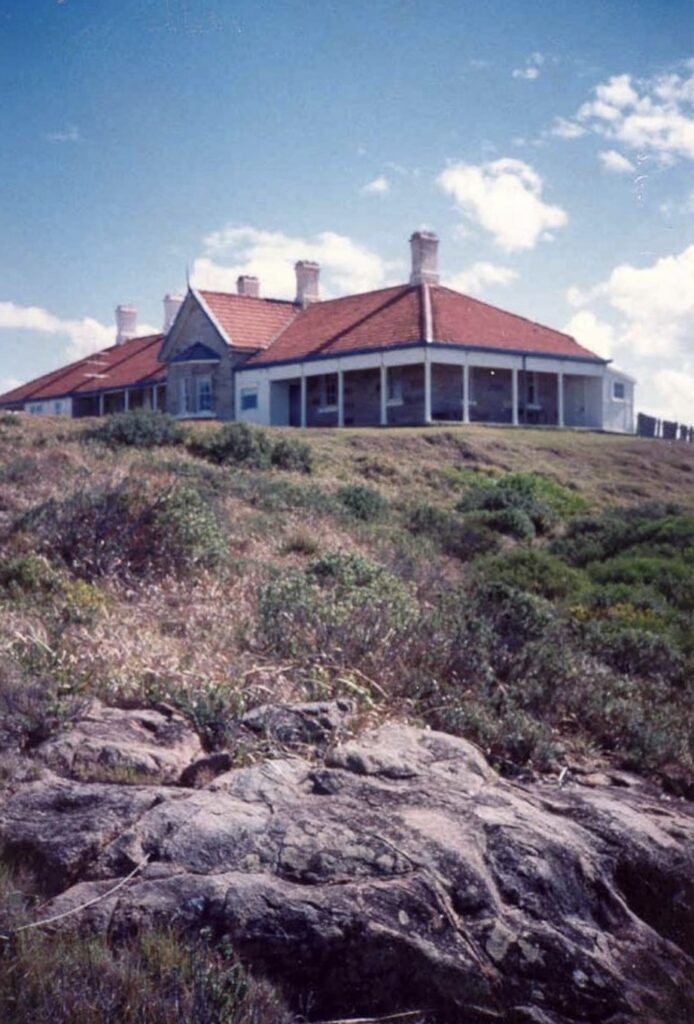

The Buildings:

Port Stephens Lighthouse’s architectural design represents a masterful balance between form and function, with its 21m tower embodying both aesthetic grace and engineering excellence. The tower’s construction from local sandstone blocks wasn’t merely a practical choice – it demonstrated remarkable foresight in material selection. The walls, tapering from nearly a meter thick at the base to a more slender profile at the top, were engineered to withstand both the constant battering of coastal winds and the potential impact of seismic activity.

The tower’s distinctive design features several innovative elements that set it apart from contemporaneous lighthouses. The tapered cylindrical shape, while visually striking, serves multiple engineering purposes – it provides optimal stability against wind forces, reduces the overall weight of the structure, and creates natural ventilation pathways essential for the original oil lamp operation. The white external finish, achieved through a specially formulated lime render, wasn’t just decorative but served to reflect solar radiation and reduce thermal stress on the sandstone.

The lighthouse complex’s layout reveals sophisticated understanding of coastal environmental challenges. The keeper’s cottages were combined within a single structure divided into individual apartments and the outbuildings were arranged in a pattern that created sheltered courtyards and protected pathways and feature several architectural adaptations to the harsh marine environment:

Some of these design features include deep verandas with specialized drainage systems to handle wind-driven rain, reinforced roof ties and extra-thick walls to withstand cyclonic conditions, carefully positioned windows and doors to maximize natural ventilation while minimizing salt spray ingress and purpose-built storage facilities designed to keep supplies dry in all weather conditions

The internal architecture of the tower demonstrates equal attention to functional detail including ; the cast iron spiral staircase features self-draining treads and corrosion-resistant mountings, each floor level incorporates ventilation ports with ingenious water-excluding designs, the lantern room’s bronze framework was specifically engineered to allow for thermal expansion while maintaining weather-tight integrity and the service rooms at various levels were positioned to create optimal weight distribution throughout the structure

The outbuildings, often overlooked but crucial to the station’s operation, included: a purpose-built signal station with clear lines of sight to the harbor entrance; a sophisticated water management system including underground cisterns and filtration; a dedicated workshop equipped for maintaining both the optical apparatus and general station equipment and storage facilities designed with specialized ventilation to prevent deterioration of supplies in the humid environment

The stone mason’s craft is particularly evident in the tower’s construction. Each sandstone block was cut to precise specifications, with many featuring complex curved surfaces to achieve the tower’s tapered profile. The joints between blocks were engineered with multiple weather barriers, including the primary mortar seals using specialized hydraulic lime mix, the secondary lead flashing in critical areas and tertiary drainage channels cut into the stone itself.

Technical Evolution:

The technological history of Port Stephens Lighthouse reflects the broader evolution of maritime navigation technology over more than 150 years. The original First Order Chance Brothers catadioptric lens assembly, which remains operational today, represents one of the finest examples of Victorian precision engineering still in active service. The lens system’s sophisticated design incorporated 1,008 individual prisms, each hand-ground to precise specifications, arranged in a hierarchical array that maximized the light’s range while minimizing energy loss.

The chronology of lighting technology transitions reveals a fascinating progression of maritime illumination techniques:

The evolution of the light source reflects the broader technological advancement of the colonial period:

- The original oil lamp system utilized colza oil, chosen for its bright, clean-burning properties

- The 1917 upgrade to kerosene involved installing a new pressurized vapor system that significantly increased light intensity

- Electrification in 1960 brought reliability but required extensive modifications to the tower’s internal structure to accommodate generators and electrical equipment

- The current automated system, while maintaining the historical character of the rotating lens, incorporates modern reliability with traditional optical principles

The original clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens assembly was a masterpiece of Victorian engineering, requiring keepers to wind it every four hours. This mechanism, manufactured by Chance Brothers, incorporated an innovative governor system to maintain consistent rotation speeds regardless of weather conditions. The original mechanism remains in place today, though disconnected, as a testament to 19th-century precision engineering.

Additional details:

- The optical apparatus included an innovative mercury float bearing system that allowed the multi-ton lens assembly to rotate with minimal friction

- The original gun metal and brass fittings were specifically designed to resist corrosion in the marine environment

- The tower’s internal ventilation system, crucial for the operation of the early oil lamps, incorporated novel features to maintain steady airflow while preventing water ingress during storms

- The original signalling apparatus included a complex system of flags and semaphore equipment for daytime communication with passing vessels

The current lighting configuration represents a careful balance between preserving historical technology and ensuring reliable operation:

- Original Chance Brothers lens maintained in operational condition

- Modern 120V 1000W quartz halogen lamp system with automated changer

- Computerized rotation control maintaining historical characteristics

- Remote monitoring and control systems

- Sophisticated backup power systems with automated failover

Keepers of the Light:

The role of lighthouse keeper at Port Stephens demanded exceptional resilience and versatility, far beyond the basic requirements of maintaining the light. The position combined the technical expertise of a skilled mechanic, the observational abilities of a meteorologist, and the administrative precision of a civil servant, all while managing life in one of the most isolated postings along the NSW coast.

The daily routine of keepers followed a rigorous schedule: 0400: First morning check of equipment and weather conditions 0545: Preparation for light extinction at dawn 0600-1200: Maintenance duties, weather observations, and record keeping 1200-1600: Equipment cleaning, repairs, and station upkeep 1600-1800: Preparation for evening lighting 1800-0400: Night watch rotation between keepers

The isolation of keeper families created unique challenges and adaptations including the development of self-sufficient food including dairy, fishing and vegetable gardens, creation of informal school arrangements for keeper’s children, innovative communication methods with the mainland and development of emergency medical response protocols

After the 1891 storm severed the peninsula connection, keepers faced additional challenges including the implementation of new supply systems, improved boat handling techniques for station access, creation of emergency evacuation procedures, establishment of backup communication systems and the installation of additional water storage and management systems.

Notable Head Keepers and their contributions:

- Thomas Walker (1862-1873), the first Head Keeper,

- William Glover (1873-1888):

- John Richardson (1888-1902):

- James McCarthy (1902-1916):

- George Harrison (1916-1928):

- James Harrison (1928-1945)

Shipwrecks & Maritime Incidents:

The waters around Port Stephens, despite the lighthouse’s vigilant presence, have witnessed numerous maritime tragedies that have become integral to the region’s maritime heritage. Each incident contributed to evolving safety protocols and often led to modifications in lighthouse operations.

SS Cawarra Disaster (1864): The loss of the SS Cawarra stands as one of the most significant maritime tragedies in the lighthouse’s early years. The vessel attempted harbor to enter the harbor during a severe southeasterly gale and despite the lighthouse being operational, extreme conditions reduced visibility to near zero. The ship was driven onto a reef and all but one of the 61 passengers and crew were lost. This incident led to installation of additional fog warning systems, prompted review of storm signal protocols and a review of the recovery efforts spawned new emergency response procedures.

Telegraph Incident (1878): The grounding of the Telegraph revealed crucial gaps in navigation procedures. The vessel struck rocks in clear conditions due to miscalculation. The following investigation revealed need for additional daymark systems, led to modification of light characteristics, resulted in publication of new approach charts and led to improved pilot services for the harbor.

Barrit Wreck (1912): This incident highlighted the challenges of navigation in poor visibility. The timber vessel mistook position during foggy conditions and was wrecked on a nearby island. This incident prompted installation of additional sound signals, led to revision of fog navigation protocols and resulted in improved weather monitoring systems. The wreckage pattern also led to identification of dangerous current patterns in an around this part of the coast.

Notable Rescue Operations:

- 12.7.1866: Mary Rose, wrecked at the entrance to Port Stephens. 5 lost, 2 saved.

- 16.2.1869: Cheldra, wrecked at Port Stephens. 1 life lost.

- 9.5.1869: Eagleton, foundered in a S.E. gale in Anna Bay, all hands lost.

- 9.5.1869: Lurline, wrecked in Port Stephens, all hands saved.

- 9.5.1869: Martha, foundered off Port Stephens, all hands lost.

- 9.5.1869: Secret, wrecked in Providence Bay, 1 life lost.

- ?.9.1869: Lavina, wrecked at Port Stephens, all hands saved.

- 28.2.1870: Trio, wrecked in Port Stephens in a N.E. gale, all saved.

- 1885 Rescue of the Mary Jane crew during hurricane conditions

- 1898 Dramatic night rescue of the Aberdeen crew

- 1923 Multiple vessel incident during unprecedented storm

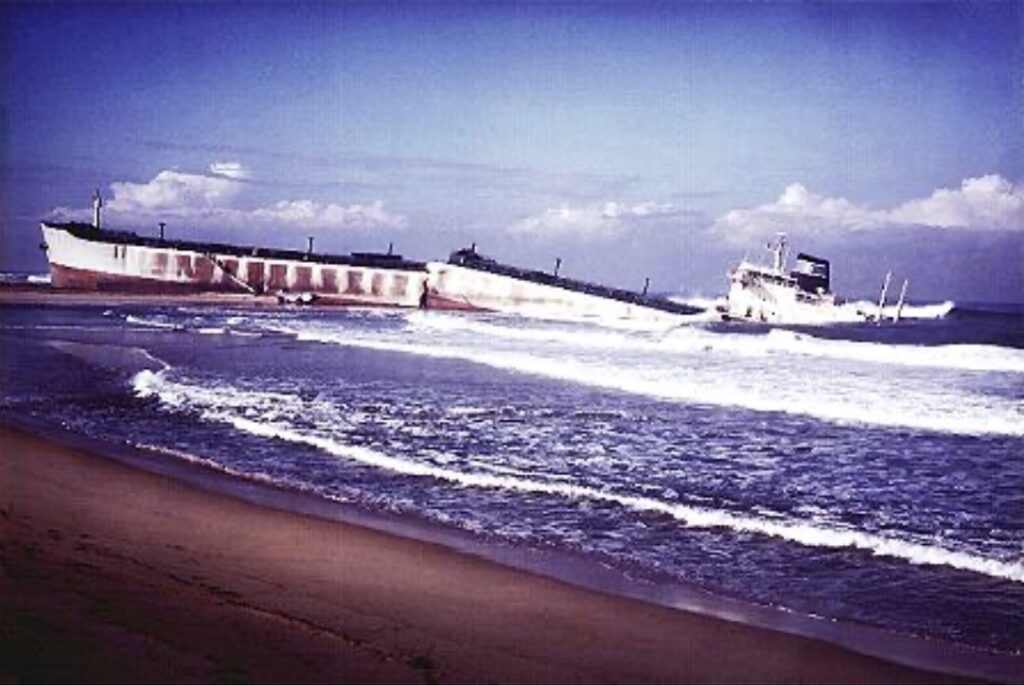

- 1929: SS Pappinbarra, wrecked on the rocks in front of the lighthouse

- 1947 Coordination of first aerial rescue operation

- 26.5.1974: M.V. Sygna driven aground and wrecked in a gale on Stockton Beach

Myths & Mysteries:

The isolated nature of Port Stephens Lighthouse has given rise to a rich tapestry of local legends and unexplained phenomena, each deeply woven into the cultural fabric of the region. While many tales can be attributed to natural phenomena, others remain enigmatic despite scientific investigation.

The Mysterious Lights Phenomenon: Multiple keeper logs from 1875-1920 document unexplained light appearing during severe storms and recurring accounts of lights appearing to mimic the lighthouse signal. Scientific investigations in the 1890s suggesting possible relationships to electromagnetic phenomena and contemporary meteorological studies indicating potential connections to rare atmospheric conditions.

The 1891 Storm Legends: The transformation of the peninsula into an island generated its own mythology. Aboriginal oral histories speaking of ancestral warnings about the impending separation. Keeper William Davies’ detailed account of unusual phenomena preceding the storm that caused the separation. There were also reports of unprecedented animal behaviour in the days before the event and of strange acoustic phenomena during the storm itself. Subsequent geological studies revealed complex underlying factors.

The Lost Keeper’s Journal: The disappearance of Head Keeper Thompson’s personal journal in 1902 spawned ongoing speculation. Evidently it contained detailed accounts of unexplained phenomena and was last seen during a routine inspection. Multiple expeditions attempted to locate it and researchers continue to search for this historical document.

Keeper logs and local records detail various inexplicable events and unexplained occurrences including:

- The “Phantom Bell” incidents of 1887-1888

- Unexplained mechanical anomalies during specific weather conditions

- Reports of unusual acoustic phenomena during calm weather

- Documented cases of inexplicable equipment behaviour

- Recurring patterns of unusual wildlife behaviour

Interesting Facts:

Port Stephens Lighthouse holds numerous fascinating distinctions and peculiarities that set it apart from other colonial lighthouses. Its unique history and operational characteristics have created a rich tapestry of notable facts that intrigue maritime historians and visitors alike.

Architectural Innovations:

- The lighthouse tower contains an estimated 2,543 individually cut sandstone blocks, each numbered during construction for precise placement

- The internal spiral staircase features an unusual left-handed twist, contrary to the typical right-handed design of most colonial lighthouses

- Hidden within the walls are copper speaking tubes, allowing keepers to communicate between levels without leaving their posts

- The tower incorporates a unique double-wall ventilation system that naturally regulates internal temperature

Operational Records:

- During its first 100 years of operation, the light was only extinguished once for 12 hours during a severe storm in 1893

- The original mercury float for the lens required 260 kilograms of mercury, which remains sealed within the mechanism today

- Keepers maintained a continuous weather record from 1862 to 1991, creating one of Australia’s longest continuous meteorological datasets

- The lighthouse holds the colonial record for the longest-serving keeper family, with three generations of the Harrison family serving from 1886 to 1945

Natural Phenomena:

- The lighthouse site has recorded over 300 different bird species, making it an important ornithological observation point

- The island’s isolation has led to the development of unique plant variants, including a distinct form of coastal banksia

- The surrounding waters feature one of the east coast’s largest seasonal congregations of whales during migration

- The site experiences an average of 17 lightning strikes per year, yet has never suffered significant lightning damage thanks to its innovative protection system

Cultural Connections:

- Indigenous rock art discovered in 1987 beneath the assistant keeper’s quarters dates back approximately 4,000 years

- The lighthouse features in numerous colonial artworks, including six paintings held in the State Library collection

- Local folklore suggests that the lighthouse’s distinctive double flash pattern was inspired by a traditional Worimi signal fire sequence

- The site hosted several significant scientific experiments, including early radio wave propagation studies in 1922

Engineering Achievements:

- The original Chance Brothers lens remains one of only three of its type still operating in the Southern Hemisphere

- The lighthouse was the first in Australia to implement a double-walled construction technique for thermal regulation

- Its unique foundation system, using dovetailed sandstone blocks, has never required major structural reinforcement

- The original rain collection system could harvest enough water to sustain three keeper families for up to eight months without mainland resupply.

Nelson Bay Inner Light:

- A secondary light house is located on a headland overlooking Nelson Bay within Port Stephens. This is unique in that it is not a purpose built lighthouse but rather a light attached to an existing house.

- It is still active and acts as a lead light for vessels entering Port Stephens.

- It serves as a maritime museum with a large collection of local maritime memorabilia and historic photos and records.

than a lighthouse!

These fascinating aspects of Port Stephens Lighthouse continue to draw interest from historians, engineers, and visitors, contributing to its significance as both a working maritime facility and a heritage site of national importance.

Current Status:

Port Stephens Lighthouse maintains its crucial role in maritime safety while evolving to meet contemporary challenges. The site’s management represents a careful balance between preserving historical significance and incorporating modern maritime safety requirements.

The lighthouse continues its essential navigation function with several modern adaptations including the integration of GPS synchronization systems for precise timing, the implementation of remote monitoring and control capabilities, the installation of backup LED systems while maintaining historical apparatus, the development of automated weather monitoring stations, the integration with national vessel tracking systems and the implementation of digital maintenance management systems.

The 2004 Commonwealth Heritage listing has brought additional responsibilities including the development of comprehensive conservation management plans, regular structural assessment and monitoring programs, specialised maintenance protocols for historical equipment, digitisation and preservation of historical records, integration of Indigenous cultural heritage management and the development of public education and interpretation programs.

Current preservation efforts focus on several key areas including active monitoring of coastal erosion, protection of historical mechanical systems, conservation of original optical equipment, integration of renewable energy systems and the preservation of traditional lighthouse keeping skills.

The lighthouse stands not only as a functional maritime aid but as a living monument to Australia’s maritime heritage, continuing to adapt while preserving its historical significance for future generations.

A Personal Note:

Despite its proximity to Sydney and significance as a 1st Order lighthouse I was unaware of its existence until recently which was embarrassing as I must have sailed past it on several occasions on my various sailing journeys between Sydney and Port Stephens without noticing it!

Initially I had difficulty finding the lighthouse as it’s on the seaward side of an offshore island and not visible from land. Once I discovered the location I was faced with the challenge of trying to access it. The eco-tour from Nelson Bay that was scheduled for later in the day was cancelled due to sea conditions and the next was scheduled until 18/12, two weeks later, which was too long to wait. The only option was to fly my drone out over 4km of open water and try and locate and film the lighthouse. This was unprecedented and I wasn’t confident it would work or even if I’d ever see my drone again. Happily, it was a great success and set a precedent for future lighthouse visits.

Equally, as I researched the history of this lighthouse I learnt of its importance in our early colonial maritime development.