Location:

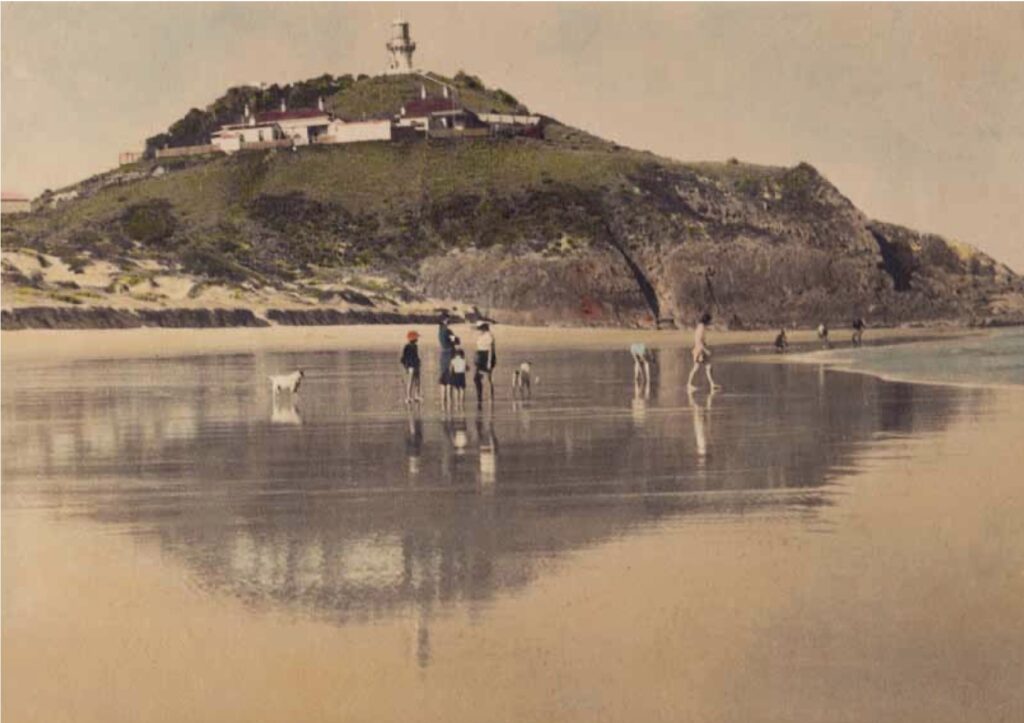

Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse stands on top of a sheer headland near Seal Rocks within the Myall Lakes National Park on NSW’s mid-north coast. The lighthouse rises 79 meters above sea level, its position carefully chosen to overlook one of the most hazardous sections of the New South Wales coastline. The lighthouse’s strategic position provides unparalleled views along the coastline, with its elevated position allowing its light to be seen up to 25 nautical miles away in clear conditions.

The promontory itself is a remarkable geological feature, jutting out into the ocean with steep cliffs falling away on three sides and connected to the mainland by a single narrow ridge. This exposed location places the lighthouse at the mercy of nature’s full force, where summer storms roll in with dramatic intensity and winter southerlies generate massive swells that crash against the cliffs below. The weather here is a constant presence, with wind speeds frequently exceeding 100 km/h during severe storms, testing both the structure’s engineering and the resilience of those who maintained it.

Summary:

GPS: Lat: 32° 26′ S Long: 152° 32′ E

First Lit: 1st December, 1875 (Automated 1987, Demanned 2007)

Tower height: 15m

Focal Height: White: 79m above MSL, Red: 73m above msl

Original Lens: First Order Chance Brothers Fresnel lens

Intensity: 780,000 candela

Range: 25 nautical miles

Characteristic: One white flash every 7.5seconds [Fl W 7.5s, Fixed Red toward south]

Indigenous History:

The story of Sugarloaf Point begins long before the lighthouse’s construction, in the deep time of Worimi custodianship. For countless generations the Worimi people held this headland as a place of profound significance weaving it into their cultural and spiritual landscape. The Traditional Owners knew this coast intimately, understanding its moods and rhythms with a depth of knowledge that came from millennia of continuous connection to Country.

Archaeological evidence speaks of this long occupation. Shell middens, carefully preserved in the sandy soils contain not just the remains of ancient meals but records of environmental change and cultural practices stretching back thousands of years. Stone tools found across the headland reveal ancient skills while rock art and ceremonial sites in the surrounding area highlight the headland’s spiritual significance.

The Worimi people developed systems for fishing and gathering using their intimate knowledge of ocean currents, weather patterns and fish movements passing down through generations of oral tradition.

From this elevated vantage point, Worimi people could track the migration of whales, vital both for their practical and spiritual significance. The headland served as a crucial communication point, allowing signals to be sent to neighbouring groups and providing a natural gathering place for ceremonies and cultural practices. This traditional knowledge and connection to place continues today with Worimi descendants maintaining their cultural links to this significant landscape.

Colonial History:

The colonial chapter of Sugarloaf Point’s story is written in the ledgers of maritime trade and, tragically, in the accounts of shipwrecks that haunted this treacherous coastline. As the colony expanded in the early 19th century the waters around the headland became increasingly busy with vessels engaged in the burgeoning regional trade. The 1820s saw the establishment of timber-getting operations in the surrounding forests, while the 1830s brought a steady increase in coastal trading vessels navigating these dangerous waters.

The discovery of coal in the Hunter Valley added another layer of maritime traffic as colliers began regular passages past the headland servicing a growing number of settlements along the north coast. This increasing volume of shipping traffic in the 1840s and 1850s brought with it a proportional increase in maritime disasters. The combination of hidden reefs, unpredictable currents, and the coast’s exposure to sudden weather changes proved fatal for many vessels.

The call for a lighthouse grew more urgent with each passing tragedy. Ship captains, merchants and local residents repeatedly petitioned the colonial government, their pleas often reinforced by the grim discovery of wreckage along the coast. Insurance companies, facing mounting losses from maritime disasters, added their influential voices to the cause. Yet it was not until the devastating loss of the Rainbow in 1864, with thirty-five souls perishing within sight of the headland, that the authorities were finally moved to act.

The Lighthouse:

The first recorded recommendation for building a lighthouse at Seal Rocks was made by a committee of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in 1863. Attended by some of the most experienced seafarers and navigators in the colony the committee was the first to evaluate the navigational needs and requirements of the country as a whole and the forerunner of the 1983 Intercolonial Maritime Conference which formulated a comprehensive plan to improve maritime safety around the continent.

At the meeting, it was reported that “the great increase of the coasting’ trade caused by the population sitting on the banks of our northern rivers, and by the rapid development of the new colony of Queensland rendered an inquiry into the facilities afforded for the safe navigation of urgent necessity”.

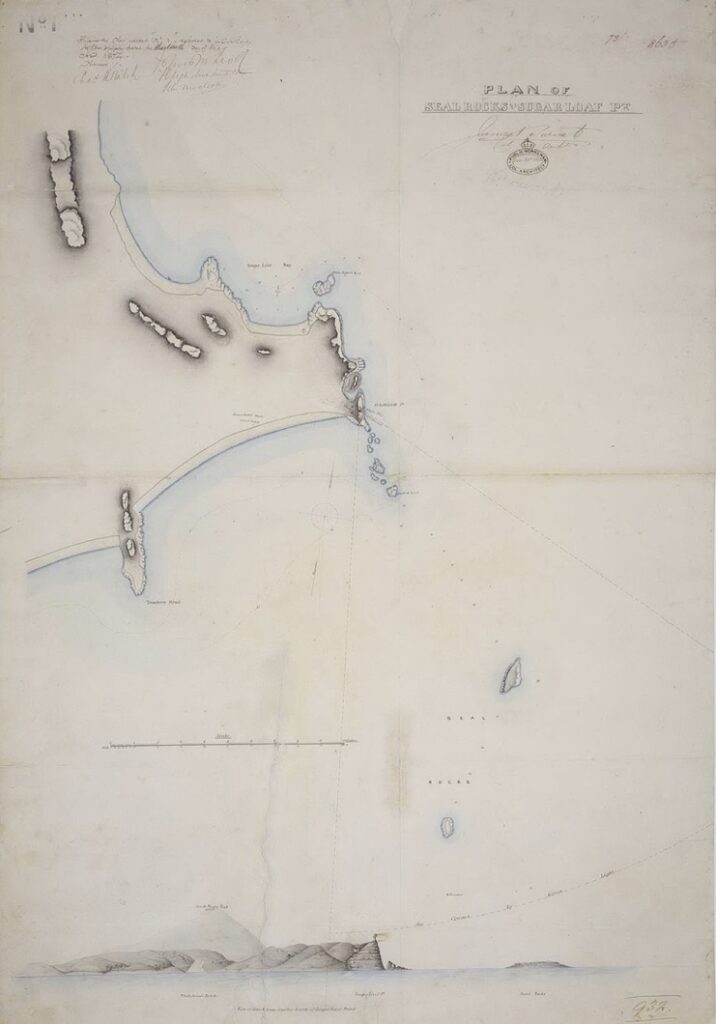

Although there was no question of the recommendations of the committee with regard to the installation of a lighthouse at Seal Rocks, it took another 10 years of negotiation to determine the most appropriate location for the light. The original intention was to place the lighthouse on the offshore rocks but because of access difficulties the Sugarloaf Point location finally chosen in 1873. On a site visit in 1873 with the Colonial Architect James Barnet the President of the Marine Board of NSW, Captain Francis Hixson, formally adopted the headland as the location for the new lighthouse.

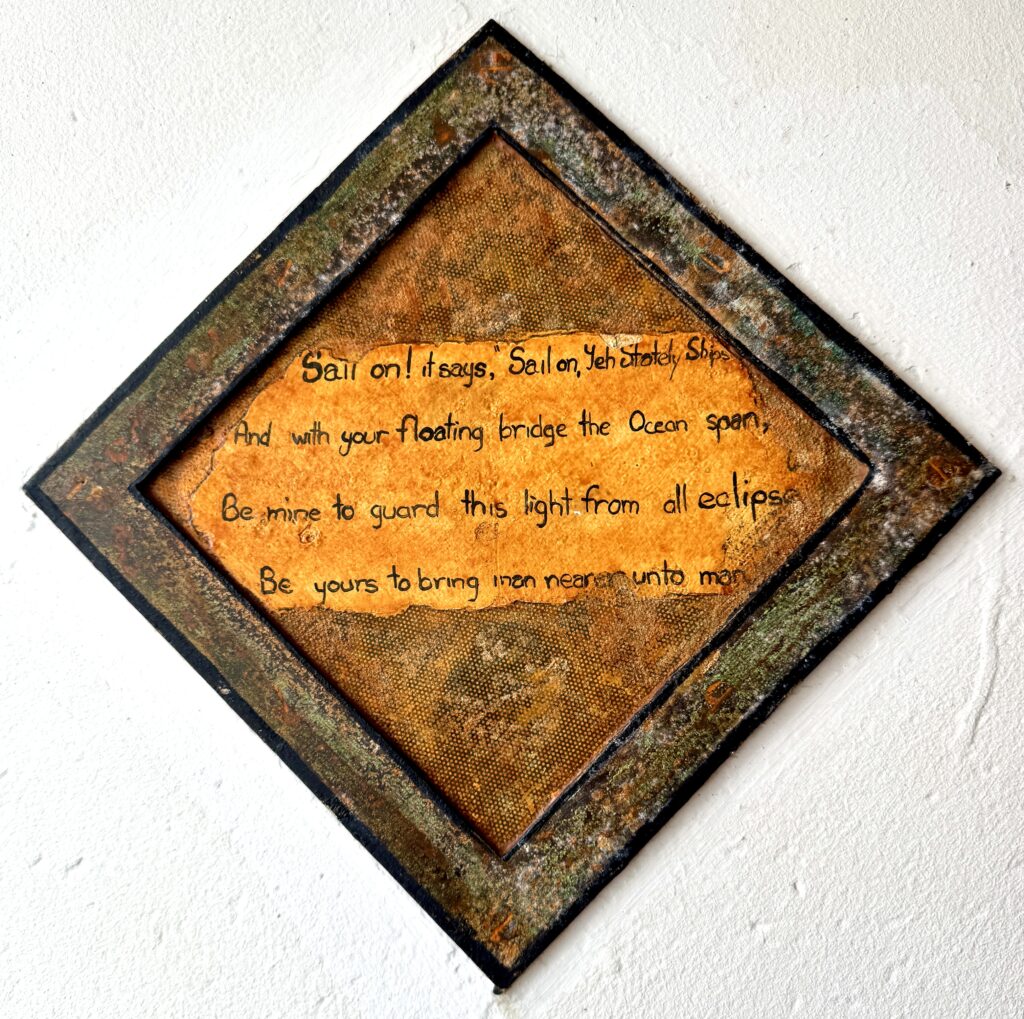

At this time, when the entire coastline and its navigational requirements were under review, Captain Hixson famously proclaimed “that he wanted the NSW coast “illuminated like a street with lamps”. Captain Hixson was ultimately successful in achieving his vision and, by the early 20th century, the “highway of lights” was complete with 25 coastal lighthouses and 12 harbour lighthouses built in NSW.

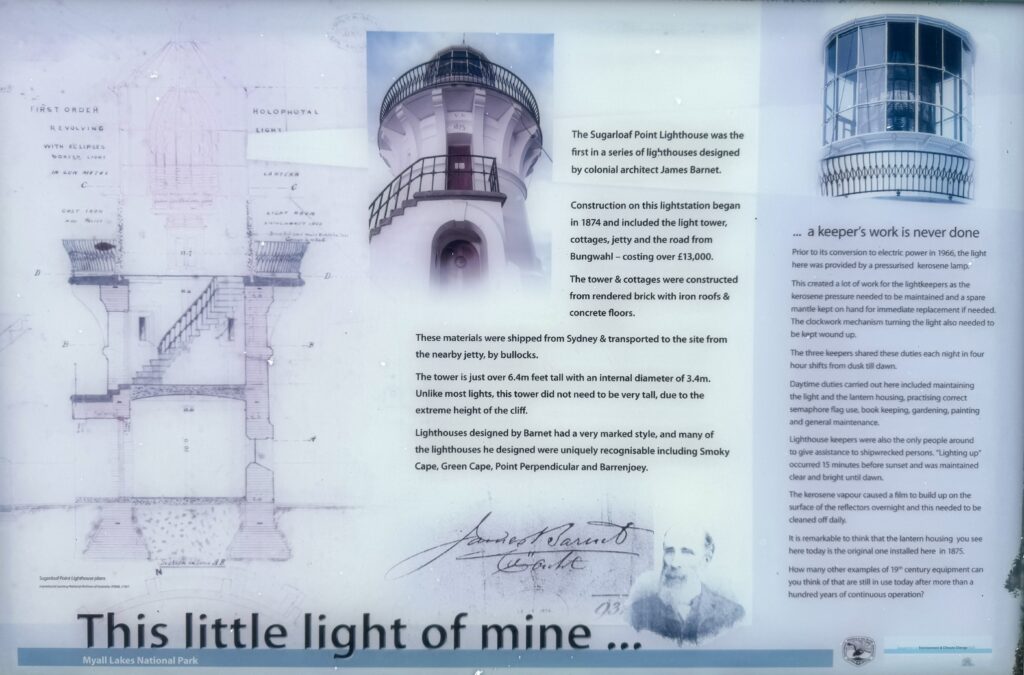

With Sugarloaf Point finally determined to be the location, Barnet set to work on plans for the tower and station and a tender was accepted from John McLeod in April 1874. Construction required building a 457m long jetty in the adjacent bay at Seal Rocks which was used to land 1,800 tonnes of supplies and materials required for the construction. A road was also built to Bungwahl leading to its development as a regional township and connecting the lighthouse to other regional centres.

The construction of Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse between 1873 and 1875 stands as a testament to Victorian engineering ambition and human perseverance. The project faced formidable challenges from the outset. The headland’s very isolation, which made it ideal as a lighthouse location, proved a significant obstacle to construction. Every piece of building material had to be carefully transported to the site, first by sea to a specially constructed jetty, then hauled up the steep headland by labourers and teams of horses.

The workforce, consisting of skilled stonemasons, carpenters, and labourers, lived in temporary camps on the headland throughout the construction. They worked through all weather conditions, their progress often hampered by violent storms that swept in from the Tasman Sea. Fresh water, essential for both construction and survival, had to be carted daily from mainland springs, adding another layer of complexity to an already challenging project.

The tower incorporated a sophisticated double-wall construction technique, providing both structural strength and natural insulation against the extreme weather conditions it would face. The ventilation system, crucial for preventing condensation on the precious lens, was integrated seamlessly into the architectural design. Even the copper dome crowning the tower was specially engineered to withstand the fierce winds that would buffet the headland. Another interesting design feature was the external stairway which is unique to Sugarloaf Point and one other Australian lighthouse.

When first lit on 1st December,1875 Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse represented the pinnacle of Victorian maritime engineering. Its First Order Chance Brothers dioptric lens, standing proudly atop the 15m tower, was a marvel of precision optics. The characteristic white flash every 7.5 seconds became a familiar and reassuring sight to generations of mariners navigating these treacherous waters. The lighthouse’s position marked it as a crucial waypoint along the busy coastal shipping routes, while its elevation of 79 meters above sea level ensured its beam could reach far out to sea, providing early warning of the dangerous coastline ahead.

Sugarloaf Point lighthouse was the beginning of a successful collaboration between Captain Hixon and was the first lighthouse designed by James Barnet, a testament to his skill in combining functional design with elegance and innovation.

The Buildings:

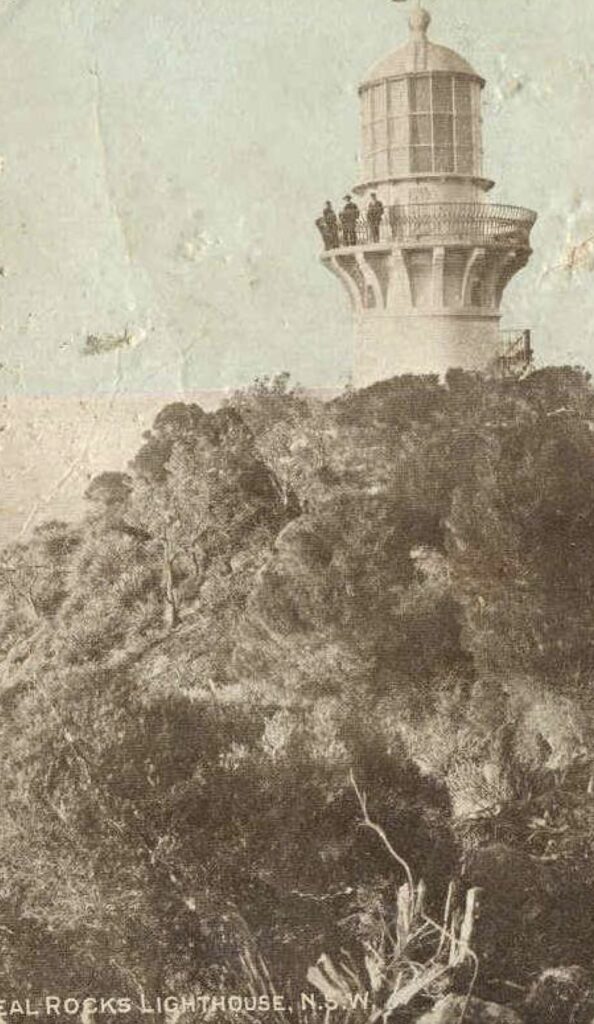

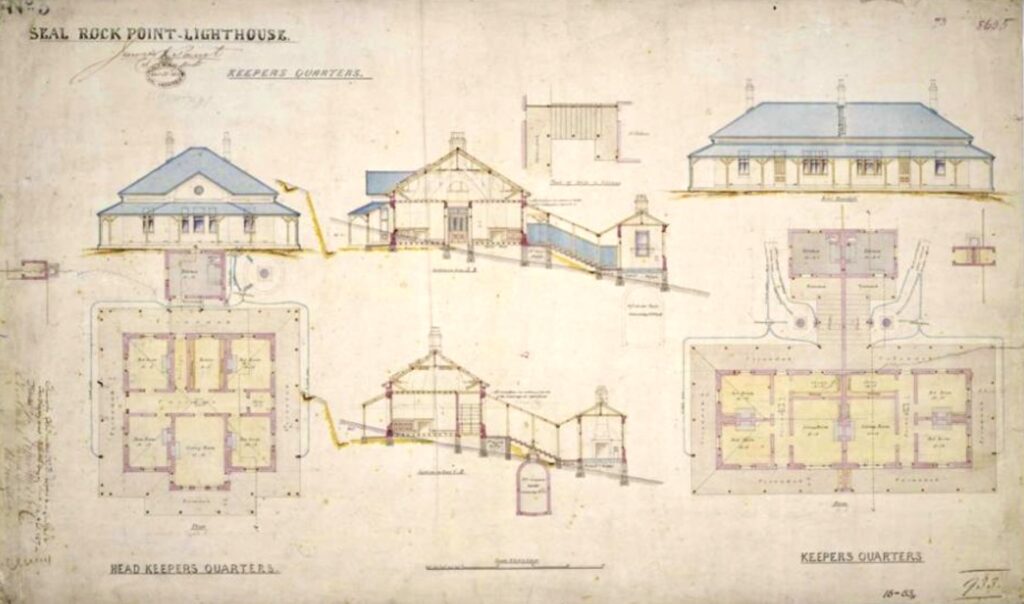

Well-proportioned, even if on a smaller scale, with the curved detailed balcony, domed oil store and heavily bracketed upper balcony (design elements that were to become characteristic of Barnet’s style as Colonial Architect), the two-storey tower was complemented by a suite of Barnet-designed mid-Victorian buildings, including a Head Keepers cottage, two Assistant Keepers cottages, signal house and paint store. To avoid the harsh elements of the coastal environment of Sugarloaf Point, the buildings were constructed below the lighthouse and on the southern side of the headland, nestled into a slight valley that sheltered the buildings and residents from the weather.

Standing 15 metres tall, the Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse is a relatively small but well-proportioned tower that retains its original Messrs Chance Bros lantern. Divided into two storeys by a concrete floor that is accessible from a distinctive external flight of bluestone steps, the tower shaft is terminated by an external lantern gallery of bluestone slabs. The lantern room is reached by an internal flight of iron steps from the concrete first floor. Encircling the external gallery at lantern floor level is the curved balustrade and handrail in gun metal that became a design characteristic of James Barnet’s architectural style. The domed oil store and heavily bracketed upper balcony also reflect Barnet’s style.

The lighthouse tower is built of bricks, cement rendered and painted white. The tower has two stories, divided by a concrete floor, the fuel store being located on the ground level. An exterior bluestone stairway reaches this floor, followed by internal iron stairs. The lantern room is 6.7m high. On top of the tower is a bluestone gallery, the projecting part being supported by concrete corbels, a Barnet design hallmark. The gallery has an elegant black gunmetal railing, another Barnet hallmark. The lantern roof is a copper dome. A brick-paved walkway surrounds the base of the tower enclosed by a 1m cement-rendered brick wall, painted white.

The Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse is complemented by a compact group of simple mid-Victorian buildings including the head keeper’s cottage, two assistant keepers’ cottages, various store rooms and stables. To avoid the harsh elements of the coastal environment of Sugarloaf Point the station buildings were separated from the tower and semaphore signal station and constructed on the southern side of the headland, nestled in a slight valley which provided a degree of shelter from the weather.

Technical Details:

Within 18 months of the location being selected, the Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse was completed and on 1 December 1875, the lantern and 1st Order sixteen panel optic was lit for the first time. An auxiliary light located on the first floor highlighting the dangers of underwater reefs and exposed rocks in the Seal Rocks sector utilises a Chance Bros 4th order fixed green lens was also incorporated in the original design

The most noticeable changes to the Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse have been its ongoing adjustment to technological improvements. The lighthouse was converted from a Chance Bros multiple wick oil burner to vaporised kerosene mantle in 1911 with a resulting increase in intensity from 50,000 cd to 122,000 cd. This was upgraded again in April 1923 to a carbide lamp with an intensity of 174,000 cd.

The original Chance Bros roller bearing pedestal was replaced with the existing Commonwealth Lighthouse Service thrust bearing pedestal as part of the conversion to electricity on 14 June 1966 which also raised the intensity to 1,000,000 cd.

The station was fully automated in 1987 and with this conversion the lighthouse was demanned and a caretaker installed on site who remained until 2007 when the residence was renovated to be used for tourist accommodations.

The current light is a 120 V 1,000 W quartz halogen lamp, powered by mains electricity with a backup diesel generator. The light intensity is 780,000 cd, and the light characteristic shown is flashing white with a cycle of 7.5 seconds. Also showing is the additional fixed red light (changed from green in 1984), with a similar 120 V 1,000 W quartz halogen lamp, visible to the south highlighting the dangers around the Seal Rocks sector.

The heart of the station was the lighthouse itself, where the sophisticated First Order Chance Brothers lens took pride of place. This masterpiece of Victorian engineering stood 3.7 meters tall and weighed approximately 8 tonnes, its 16 precisely crafted glass prism panels designed to capture and focus the light into a powerful beam visible for 25 nautical miles. The entire apparatus floated on a bath of mercury, allowing it to rotate with remarkable precision despite its enormous weight.

The early years of operation required intense physical labour and meticulous attention to detail. The original colza oil lighting system demanded constant attention, with keepers climbing the tower every four hours to trim wicks, adjust the flow of oil, and wind the clockwork mechanism that drove the rotation of the lens. The management of supplies became a critical task – every drop of oil, every spare wick, and every maintenance tool had to be carefully accounted for, as resupply could be months away.

The transition to kerosene in 1911 brought new challenges and opportunities. The kerosene vapor system provided a brighter, more reliable light, but it also introduced new complexities in operation and safety protocols. Pressurized fuel tanks required regular maintenance, and the risk of fire meant that keepers needed to be even more vigilant in their duties.

The arrival of electricity in 1966 marked a revolution in lighthouse operation. The installation of diesel generators, later supplemented by connection to mains power, transformed the daily routines that had governed lighthouse life for nearly a century. Yet even as automation crept in, the importance of human oversight remained. The keepers adapted to new technologies while maintaining the traditional skills that had kept the light burning through decades of technological change.

Keepers of the Light:

The story of Sugarloaf Point’s keepers spans 91 years and several generations, beginning with William Bramley who took up his position as the first Head Keeper in 1875. Bramley established many of the routines and protocols that would govern life at the station for decades to come, including the meticulous system of watch schedules and maintenance procedures that ensured the light’s continuous operation.

The keeper’s duties were both physically demanding and technically precise. Every evening, as dusk approached, the keeper on duty would climb the 15m tower to light the lamp, having already cleaned the lens and checked all equipment during daylight hours. Throughout the night, four-hourly watches required vigilant attention to the light’s operation, with each keeper responsible for maintaining the correct fuel flow, trimming wicks, and monitoring weather conditions that might affect shipping.

John McCarthy replaced William Bramley as Head Keeper in 1886 and marked the beginning of what many consider the station’s golden age. McCarthy was known for his innovations in lighthouse maintenance, developing techniques that would later be adopted at other stations along the coast. His wife Mary became the station’s unofficial doctor, her medical skills tested by everything from minor injuries to childbirth. Their daughter Catherine’s detailed diaries provide a vivid picture of daily life, describing how the families gathered for celebrations, supported each other through hardships, and found joy in their isolated but purposeful existence.

The isolation of the position attracted a particular breed of lighthouse keeper. Many, like James Thompson (Head Keeper 1902 -1920), brought their families to the station, creating a close-knit community that shared both hardships and celebrations. Thompson’s wife Sarah took it upon herself to act as schoolteacher for the children of the families on station and also became known for her skill in treating injuries and illnesses, as the nearest doctor was often days away. Their detailed logbooks and personal correspondence provide vivid insights into daily life at the station, from the mundane tasks of maintaining vegetable gardens to dramatic rescues during storms.

The wartime years brought additional responsibilities to the keepers. During World War II, Head Keeper Richard Morrison (1939-1945) and his staff maintained 24-hour surveillance for enemy vessels while continuing their regular duties. The station’s strategic position made it an important observation post, with keepers required to report any unusual maritime activity to naval authorities. Morrison’s logbooks detail several incidents of suspicious vessels and potential submarine sightings, though many records from this period remain classified. The keepers’ families shared the burden of these additional duties, maintaining blackout conditions and managing with even greater isolation as wartime restrictions limited supply deliveries.

The modernisation of the lighthouse brought significant changes to the keepers’ roles. The transition to electric power in 1966 eliminated many physical tasks but introduced new technical responsibilities. The last permanent keepers, including Head Keeper Michael Buckley (1975-1987), became skilled electricians and mechanics, maintaining both the traditional equipment and modern systems. When automation finally came in 1987, it marked the end of an era that had seen 17 different Head Keepers and countless assistants maintain this vital maritime beacon.

Head Keepers:

- William Bramley (1875-1886)

- John McCarthy (1886-1902)

- James Thompson (1902-1920)

- Michael O’Brien (1920 -1928)

- James Harrison (1928-1939)

- Richard Morrison (1939-1945)

- Thomas Hansen (1945 -1953)

- Incomplete records (1953 – 1975)

- Michael Buckley (1975-1987) – Last Head Keeper before automation

- Mark Sheriff (2006-2007) – Caretaker

Shipwrecks & Tragedies:

The waters around Sugarloaf Point have witnessed numerous maritime disasters, each etching its story into the station’s history. The loss of the Rainbow in 1864 when 35 people perished within sight of the future lighthouse site, proved a catalyst for the station’s construction. However, this tragedy would be followed by many others despite the lighthouse’s presence.

1876 marked a particularly dramatic year, when three vessels – the Hoolet, Merchant, and Susannah Cuthbert – found themselves simultaneously in distress during a fierce storm. While the Merchant and Susannah Cuthbert managed to reach safety, the Hoolet’s fate proved tragic. Captain James McKenzie’s initial reluctance to abandon ship proved fatal for one passenger, who was swept away after their lifeboat capsized in the heavy surf. The lighthouse keeper’s detailed account describes desperate attempts to assist survivors as they struggled ashore through mountainous seas.

The 1891 loss of the Ellen stands as one of the coast’s most harrowing survival stories. After abandoning their sinking vessel, nine crew members drifted for ten days in a damaged lifeboat without provisions. Keeper’s logs record the tragic discovery of six bodies along the shoreline, with only one survivor – Second Mate Thomas Williams – being strong enough to reach the lighthouse. Williams’ account of watching his shipmates succumb one by one to exposure and thirst was recorded in detail by Head Keeper McCarthy, providing a grim testament to the ocean’s merciless nature.

Perhaps no incident captures the perilous nature of these waters more vividly than the loss of the SS Catterthun in 1895. The Chinese steamer, bound for Hong Kong with passengers and a valuable cargo of gold, met its fate on an uncharted reef during a violent storm. Despite the lighthouse keepers’ desperate attempts to organize rescue efforts, fifty-five lives were lost that night. The tragedy unfolded in full view of the lighthouse, with keeper John McCarthy and his assistants helplessly watching as passengers and crew struggled in the mountainous seas. For weeks afterward, the keepers documented the recovery of bodies and debris along the coastline, with some victims’ remains washing ashore up to 30 kilometres away.

Yet not all tales from these waters end in tragedy. The rescue of the Tuggerah’s crew in 1919 stands as a testament to the courage and resourcefulness of the lighthouse community. When the coastal steamer struck rocks during a severe storm, Head Keeper James Thompson and his team executed a daring rescue. Using the station’s rocket apparatus – a complex system designed to shoot rescue lines to stricken vessels – they managed to establish a connection to the foundering ship. Over several harrowing hours, they brought the entire crew safely ashore, with the keeper’s quarters transformed into an emergency shelter and hospital.

The 20th century brought new categories of maritime incident to Sugarloaf Point. During World War II, the Austrian freighter Vienna ran aground while attempting to evade suspected enemy submarine activity. Though her crew survived, the incident highlighted the additional perils faced by merchant vessels during wartime. The wreck became a navigation hazard in its own right, requiring adjustment of the lighthouse’s warning signals to prevent further accidents in the area.

Pre-Lighthouse Era

- 1864 – SS Rainbow. This tragedy became catalyst for lighthouse construction with 35 lives lost within sight of future lighthouse site

Post-Lighthouse Era

- 1876 – The Hoolet, Merchant and Susannah Cuthbert all came to grief in the same storm. Lighthouse staff involved in multiple rescues and miraculously only one fatality.

- 1891 – The Ellen. Nine crew members adrift for ten days with only one survivor (Thomas Williams) and six bodies recovered along shoreline

- 1895 – SS Catterthun. Major maritime disaster with 55 lives lost. Struck uncharted reef during storm with bodies and debris found up to 30km away

- 1919 – SS Tuggerah. Coastal steamer struck rocks during severe storm. Successful rescue operation led by Head Keeper James Thompson using recently developed rocket propelled lifeline.

- 1921 – SS Fitzroy. Capsized during gale off Cape Hawke while travelling between Coffs Harbour and Sydney. 31 of 36 on board perished. It’s also recorded that a passenger was lost overboard off Seal Rocks in 1920;

- 1943 – Vienna. Austrian freighter which ran aground while evading suspected Japanese submarine.

Modern marine technology has fundamentally changed the nature of maritime risk around Sugarloaf Point but hasn’t eliminated it entirely. Today’s challenges often involve pleasure craft and fishing vessels, with the lighthouse continuing to play a crucial role in preventing disasters. The local volunteer marine rescue organization maintains records of numerous incidents where the lighthouse’s reliable beam has helped distressed vessels find their way to safety, adding new chapters to its long history of maritime service.

Myths & Mysteries:

Like many isolated maritime outposts, Sugarloaf Point has accumulated its share of unexplained phenomena and local legends. The most persistent of these involves the “Lady of the Light,” first documented in keeper’s logs during the 1890s. Multiple keepers and family members have reported encounters with a young woman in Victorian-era dress, often seen during storms or preceding maritime emergencies. Some associate her with Catherine Zhou, lost in the Catterthun disaster, while others believe she predates the lighthouse itself.

The keeper’s logbooks contain numerous accounts of unexplained phenomena. During his tenure in the 1920s, Head Keeper Michael O’Brien maintained a separate journal dedicated to documenting mysterious lights observed at sea. These illuminations, witnessed by multiple keepers, moved in patterns that defied both the physics of known vessels and prevailing weather conditions. O’Brien’s successor, James Harrison, continued these observations, adding accounts of inexplicable sounds within the tower that seemed to presage approaching storms.

The winter of 1943 stands out for a particularly well-documented series of unexplained events. Over several weeks, all three keeper families reported identical experiences: footsteps in the empty tower, lights appearing in unoccupied cottages, and most notably, a woman’s voice singing during the most severe storms. These occurrences became so frequent that they were officially recorded in station records, though no explanation was ever confirmed. Some connected these events to wartime tensions, while others saw them as manifestations of the station’s complex history.

A fascinating discovery during renovation work in 1962 added another layer to the lighthouse’s mysteries. Workers uncovered a sealed compartment in the tower’s base containing an intricately engraved ship’s bell bearing markings consistent with 17th-century Dutch or Portuguese craftsmanship. Its presence remains unexplained, as no documented shipwrecks from these nations match the bell’s apparent age. The artifact, now preserved in a regional museum, continues to intrigue maritime historians and archaeologists.

The headland’s mysteries extend beyond European history. Worimi oral traditions speak of the point as a place where physical and spiritual worlds intersect, particularly during whale migration seasons. These traditional accounts have found curious parallels in modern experiences, with several documented cases of unusual atmospheric phenomena and unexplained light patterns over the water. Local Indigenous elders maintain these occurrences are natural manifestations of the headland’s spiritual significance, representing the continuing connection between land, sea, and spirit that has existed here for countless generations.

Current Status:

Today, Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse stands as both a working aid to navigation and a living memorial to Australia’s maritime heritage. Though the last keeper departed in 1987, the lighthouse continues its nightly vigil, its automated beam sweeping across waters that have witnessed countless stories of tragedy and triumph. The transition from manned operation marked not an ending, but rather the beginning of a new chapter in the station’s long history.

The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service has undertaken painstaking conservation work to preserve both the physical structures and their historical significance. The process of restoration has been guided by a deep respect for the site’s heritage values, balancing the needs of modern safety standards with the preservation of authentic historical features. Each project, from the stabilisation of the tower’s foundations to the restoration of the keeper’s cottages have revealed new layers of the station’s history through the discovered of artifacts and architectural details.

The keeper’s cottages have been transformed into unique heritage accommodation, allowing visitors to experience something of the isolation and drama that characterised lighthouse life. The restoration work carefully preserved original features while discretely incorporating modern amenities. Victorian-era wallpapers, discovered during renovation, were meticulously reproduced. Original timber work was conserved where possible with any replacements crafted using traditional techniques. Each cottage tells part of the lighthouse story through carefully chosen furnishings and interpretive materials that help visitors connect with the lives of former residents.

Perhaps most remarkably, the original Chance Brothers lens continues its service, now powered by modern LED technology but still rotating on its historic mercury bath bearing. This masterpiece of Victorian engineering has maintained its vigil for nearly 150 years, making it one of the oldest functioning lighthouse mechanisms in Australia. Regular maintenance ensures its preservation while maintaining its vital role in maritime safety. The characteristic a white flash every 7.5 seconds remains unchanged, providing a living link to generations of mariners who have relied on its guidance.

The site has become an important centre for education and research. School groups regularly visit to study not only maritime history but also the area’s unique ecology and Indigenous heritage. Researchers come to study everything from colonial architecture to marine biology, adding new dimensions to our understanding of this significant place. The surrounding national park protects important wildlife habitat, including breeding sites for several endangered seabird species that the keeper families once monitored as part of their duties.

Recent years have seen growing recognition of the site’s broader cultural values. Management plans now encompass the interconnected stories of Indigenous occupation, colonial maritime history, and ongoing environmental significance. This holistic approach acknowledges that the lighthouse’s significance extends far beyond its role as a navigational aid representing layers of human interaction with this dramatic coastal landscape spanning thousands of years.

As climate change brings increasingly severe weather events to the coast the lighthouse’s role in maritime safety remains as relevant as ever. While modern vessels rely primarily on electronic navigation systems the reassuring flash of Sugarloaf Point continues to provide a vital backup system and a tangible connection to Australia’s maritime heritage. In this way the lighthouse maintains its historic mission while adapting to serve the needs of a new generation of mariners, standing as a testament to both technological innovation and enduring human resourcefulness in the face of nature’s challenges.

Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse is operated by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, while the structures are owned and maintained by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The lighthouse and surrounding buildings were added to the Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004 and the New South Wales Heritage Register on 22 February 2019.

Although the tower is closed the keepers’ cottages can be rented for short term stays, the grounds and lookout are open to the public from sunrise to sunset each day.