Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse stands at the most south-westerly point of the Australian mainland, where the Indian and Southern Oceans meet in a wild tumult of competing swells and currents. Rising 39m from its granite foundations it remains mainland Australia’s tallest lighthouse. The white tower has guarded this treacherous passage since December 1896 with its powerful beam sweeping across waters that have claimed countless vessels over the past two hundred years. The lighthouse marks one of the southern hemispheres three great capes, standing alongside the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn and marking the edge of the known world for generations of early mariners.

The Wardandi people, one of fourteen Noongar language groups of south western Australia are the traditional custodians of this land for literally thousands of generations before European arrival. They knew the cape as Doogalup and understand its flora and fauna, weather and seasons with an intimacy born of millennia. Archaeological evidence from nearby Devil’s Lair cave near Augusta reveals Noongar occupation dating back between 12,000 and 50,000 years, and is among the oldest continuous cultures on Earth. The Wardandi maintained sophisticated knowledge of the coastal environment with fish traps documented near Cape Leeuwin by early European explorers who marveled at the ingenious system.

European contact began in March 1622 when the Dutch ship Leeuwin, meaning “Lioness”, under the command of Master Jan Fransz and on assignment to the VOC (Dutch East India Co) charted portions of the nearby coastline, though unfortunately her log has been lost to history. The land they discovered appeared on Hessel Gerritsz’s 1627 map as “Leeuwin’s Land.” French explorer Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux sighted the cape in 1791 mistaking it for an island and naming it St Alouarn Island. Ten years later Matthew Flinders began his historic circumnavigation of Australia (or New Holland or Terra Australis as it was still called in some quarters), from this very point, naming it Cape Leeuwin in honour of the Dutch vessel and recognising it as the south-western extremity of the continent.

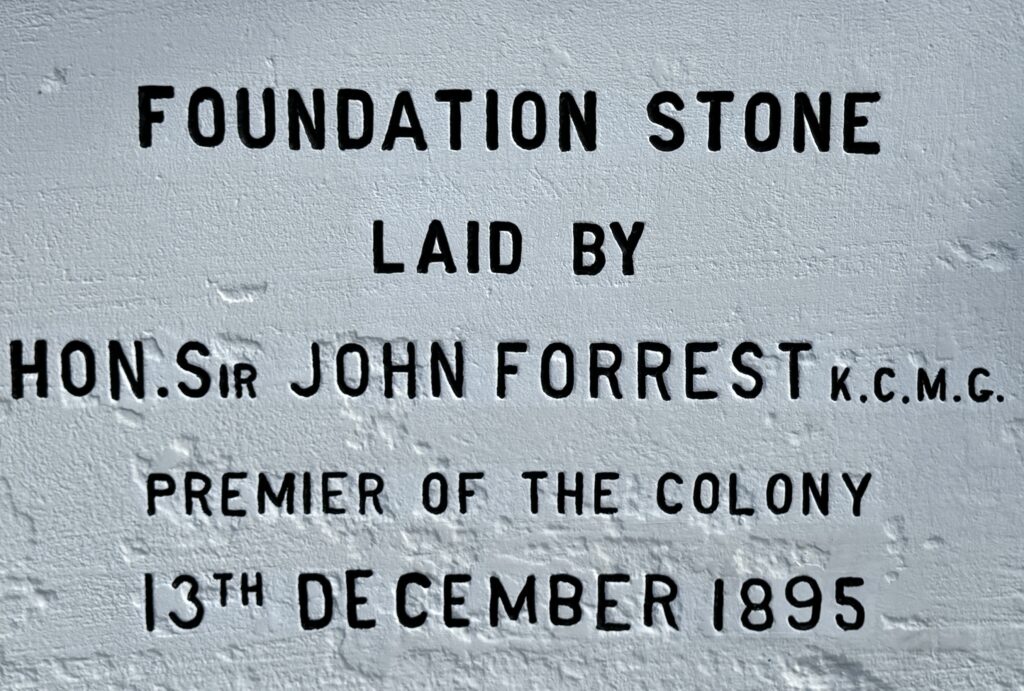

Agitation for a lighthouse began around 1880, with various sites proposed including St Alouarn Island. Local entrepreneur M.C. Davies, whose timber mills exported vast quantities of jarrah and karri from ports in the region became a passionate advocate for need for a lighthouse. However Western Australia remained the poorest of the Australian colonies and unable to afford such major infrastructure. The discovery of gold near Kalgoorlie in the 1890s finally provided the necessary funds and construction began in 1895 under a contract awarded to Davies and Wishart for just under £8,000 exclusive of the dome and light.

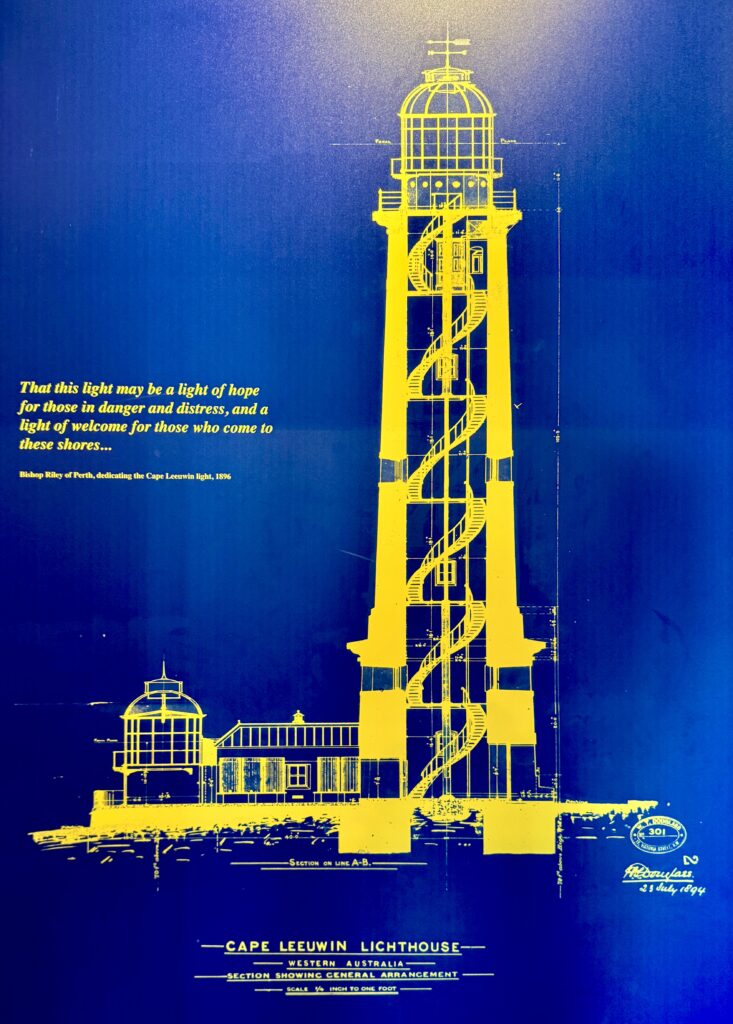

The lighthouse was constructed from local Tamala limestone quarried at nearby Quarry Bay with blocks transported to the site via temporary horse drawn railway. Foundations were excavated 23 feet down to the granite bedrock, deeper than anticipated which significant causing delays. The original 1895 plan called for two lights, the present 39m white light tower and a lower red light tower in front of it. Although foundations for the lower tower were completed it was never built as authorities feared a second light would confuse mariners and draw ships dangerously close to the cape. The tower was fitted with a magnificent first order bi-valve Fresnel lens manufactured by Chance Brothers of Birmingham, England. Cape Leeuwin became the first lighthouse in Australia and one of the first in the world to use a Chance Brothers mercury pedestal enabling the lens to revolve every 10 seconds, a massive improvement over the roller bearing pedestals then in use. The original light source was a six-wick kerosene lamp producing 250,000 candelas and visible for 20 nms.

Premier Sir John Forrest performed the official dedication on December 10, 1895, declaring that in constructing the light from its own resources the colony had done its duty not only to its own people but to all the mariners of the earth. His words held special significance as the light guards one of the busiest sea traffic routes on the Australian coast. In the days when most Australian-bound ships travelled via the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin was often the first Australian landfall. Three stone keepers’ quarters were built to house the lighthouse families in this isolated outpost and life revolved around constant vigilance. The lighthouse was manually operated until June 1982 using a counterweight driving the clockwork mechanism with keepers climbing the tower multiple times a day and night to wind the mechanism and pump kerosene to the burner. The light was subsequently upgraded in 1925 to vaporized kerosene, increasing intensity to 780,000 candelas.

Among the colourful stories attached to Cape Leeuwin is the disputed claim that Felix von Luckner, who later became a German World War I naval hero commanding the commerce raider SMS Seeadler, briefly worked as an assistant to the lightkeeper around 1901. According to his memoir, he abandoned the position when discovered with the lightkeeper’s daughter was sired by her father. While some details of his account don’t match reality, e.g. he claimed the lighthouse was 100 metres high and stood on 100-metre cliffs, neither of which is true, other aspects suggest he may have visited when the German ship Caesarea called at nearby Flinders Bay in July 1901 to load timber for Liverpool.

The most dramatic maritime event in the lighthouse’s history occurred on March 31, 1910, when the luxury liner SS Pericles struck an uncharted rock near St Alouarn Island in clear weather. Built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, the same shipyard that would later construct the Titanic, the 10,925 ton vessel was the pride of the Aberdeen Line fleet. Within three minutes of striking the reef there was five metres of water in her forward hold. Captain Alexander Simpson, who had 46 years’ experience at sea, gave the order to abandon ship. The lighthouse keepers lit signal fires ashore to guide the lifeboats through darkness to safe landfall in Sarge Bay. All 300 passengers and 150 crew survived with only the ship’s one-eyed cat, Nelson, lost. The keepers’ heroic efforts earned them awards from the Royal Humane Society of Australasia. The wreck now lies seven kilometres from the lighthouse in 34 metres of water, the largest passenger liner to ever sink off the Australian coast.

A remarkable engineering feature associated with the lighthouse is the waterwheel constructed in 1895 to bring fresh spring water to the site. Located about one kilometre north in a small cove, the timber waterwheel sat above the high tide line and powered a hydraulic ram that pumped water uphill to the keepers’ quarters. Over decades, the waterwheel became encrusted with layers of limestone from the mineral-rich water, gradually calcifying until it became virtually frozen in rock, a striking industrial sculpture against the natural environment. The waterwheel served until 1978 when the lighthouse and cottages were connected to the Augusta town water supply.

The lighthouse was automated in 1982 and converted to electricity, replacing the clockwork mechanism and kerosene burner with a 1,000-watt halogen lamp that increased output to 1,000,000 candelas.

Today it continues as a vital navigation aid while serving as an important automatic weather station, maintaining the longest unbroken record of weather data in Western Australia since recording began on January 1, 1897. The lighthouse and its eight-hectare reserve have become a premier heritage tourism destination, with one of the original stone cottages housing an award-winning Interpretive Centre that brings to life the extraordinary experiences of lighthouse families who once lived at the edge of the continent. The white limestone tower stands as testament to Western Australia’s maritime heritage and the enduring human need to bring light to darkness and safety to unpredictable and dangerous waters.

Technical Summary

First Exhibited: December 10, 1896

Status: Active (Automated, unmanned since 1996)

Location: Cape Leeuwin Road, Augusta, Western Australia (approximately 315 kilometres south of Perth)

Historical Significance: Tallest lighthouse on mainland Australia; located at most south-westerly point of Australian continent where Indian and Southern Oceans meet; one of the world’s three “great capes”; first Australian lighthouse to use Chance Brothers mercury pedestal

Construction Cost: Just under £8,000 (1895, exclusive of dome and light)

Construction Period: April 1895 – December 1896

Construction Material: Local Tamala limestone quarried from Quarry Bay

Tower Height: 39 metres

Focal Height: 56 metres above sea level

Foundation Depth: 23 feet (7 metres) to granite bedrock

Lantern House: Chance Brothers, Birmingham, England

Optical System: First-order bi-valve Fresnel lens (Chance Brothers), revolving in mercury bath

Mercury Bath: First in Australia to use Chance Brothers mercury pedestal

Rotation Period: Every 10 seconds

Original Power: 250,000 candelas (six-wick kerosene lamp)

Upgraded Power: 780,000 candelas (vaporized kerosene, 1925)

Current Power: 1,000,000 candelas (1,000-watt halogen lamp, 1982)

Visibility: 26 nautical miles (nominal range)

Characteristic: One flash every 7.5 seconds (Fl W 7.5s)

Manual Operation: 1896-1982 (counterweight driving clockwork mechanism)

Automation: 1982; last keeper departed 1996

Management: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Indigenous Heritage: Traditional lands of the Wardandi people (Doogalup); 45,000+ years of occupation

European Exploration: Named 1801 by Matthew Flinders after Dutch ship Leeuwin (1622)

Keepers’ Quarters: Three original stone cottages (1896), three still standing

Historic Precinct: 8 hectares within Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park

Weather Station: Longest unbroken weather recording in Western Australia (since January 1, 1897)

Tower Access: 176 steps to viewing deck

Associated Heritage Structure:

Cape Leeuwin Waterwheel: Timber waterwheel and flume (1895), powered hydraulic ram to pump fresh spring water from nearby spring to lighthouse quarters; now calcified and heritage-listed; located approximately 1 kilometre north of lighthouse in small cove

Notable Historic Events:

- March 31, 1910: SS Pericles sinking – all 450 passengers and crew rescued by lighthouse keepers’ signal fires; largest passenger liner to sink off Australian coast

- Original Fresnel lens shipment lost at sea en route from England; replacement lens still in operation after 129 years

- Disputed connection to Felix von Luckner, later WWI German naval hero