Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse stands majestically on a 100m bluff overlooking Geographe Bay, its roughly-hewn white limestone tower rising 20m above the windswept promontory. First exhibited in 1904, this lighthouse represents a pivotal achievement in Western Australia’s maritime infrastructure made possible by the 1890s gold rush that finally provided the colony with funds to undertake major capital works programs. The lighthouse continues to stand watch over one of the most treacherous stretches of the south-west coast with its original first-order Fresnel lens still rotating as it has for over 120 years and with the last lighthouse keeper departing in 1996 it was the last manned lighthouse on mainland Australia.

Before European contact this magnificent headland belonged to the Wadandi people one of fourteen Noongar language groups inhabiting the south-west of Western Australia. The Wadandi maintained an intimate knowledge of this land for at least 40,000 years with an intimate understanding of its changing seasons and abundant natural resources. The coastline held deep spiritual significance, with nearby places bearing names that spoke to this ancient connection, i.e. Yallingup means “place of caves”, Meekadarabee “the moon’s bathing place”, and Boranup “place of the male dingo.”

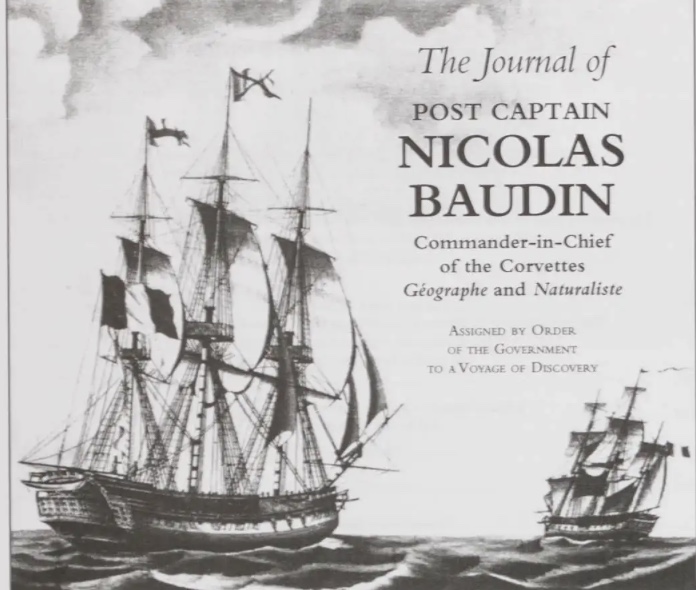

European contact first came during the age of exploration and imperial ambition. In May 1801, French explorer Nicolas Baudin made landfall at what he named Geographe Bay after his flagship. Baudin’s expedition, commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte, was one of the most lavishly equipped scientific ventures of its time. The two corvettes, the Géographe and Naturaliste carried 22 scientists including naturalists, botanists, geologists, and artists. Cape Naturaliste received its name from the expedition’s second ship. Despite mounting tensions and Baudin’s failing health from tuberculosis, the expedition secured the most valuable natural history collection of its time including more than 200,000 specimens of flora and fauna, of which 2,542 were new to science.

For the century following Baudin’s visit, mariners navigating these dangerous waters depended on a remarkably modest navigational aid known as “The Tub” which was no more than a barrel perched atop a 30-foot pole which was located at Busselton. This primitive beacon proved woefully inadequate as maritime traffic increased. The waters off Cape Naturaliste became a graveyard of ships. The Halcyon was completely wrecked in 1844. The Day Dawn, the Gaff and the Dao were all driven ashore during the fierce gales that sweep in from the Southern Ocean with regularity. Three American whaling vessels were lost on a single devastating day in July 1840; the Samuel Wright, the North America and the Governor Endicott.

Construction of Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse began in 1903, taking just ten months to complete at a cost of £4,800. The lighthouse was built from local limestone quarried about one mile from the site with bullock wagons hauling the massive blocks across rugged terrain. The tower was fitted with a magnificent 14-foot diameter lantern manufactured by Chance Brothers of Birmingham, England. The first-order Fresnel lens, crafted from lead crystal and weighing 12.5 tons, floats on 156.5 kilograms of mercury, though in an almost poetic mishap the original mercury shipment arrived safely from England only to be lost overboard at Quindalup jetty and it took over a year for replacement to arrive. Three stone keepers’ quarters were constructed to house the lighthouse families and built to withstand the wild ocean storms that frequent this most isolated and exposed location.

Life for the lighthouse keepers and their families was characterised by isolation, hardship, and unwavering dedication. Three keepers maintained constant vigilance with their night watches divided into three periods. During each watch the keeper wound the clockwork mechanism and pumped kerosene to the burner. The lighthouse prisms required cleaning at least once a fortnight, a task that took two men the better part of a day. With no paid annual leave the keepers remained at their isolated stations for many years without a break and the nearest school was 20 kilometres distant at Quindalup, forcing families to homeschool their children.

Carl Hansen, Cape Naturaliste’s first head keeper, experienced devastating personal loss when his wife died while giving birth to twins in 1904 just as the lighthouse began operations. Five years later his son died of rheumatic fever in Cottage One, another casualty of the isolation and limited medical access that characterised lighthouse life.

The year 1907 proved particularly eventful. During a severe electrical storm in July a fireball struck the lighthouse causing immense damage to both tower and quarters. The head keeper suffered a head wound requiring stitches with a doctor brought 25 miles to the lighthouse. He remained off duty for eight weeks and the family was left traumatised during every subsequent storm. That same year the lighthouse played a crucial role in rescuing fourteen survivors from the Carnarvon Castle which caught fire after a boiler exploded when the ship was 120km south west of the cape. After enduring 24 days in lifeboats the desperate sailors were guided to land by the Cape Naturaliste light. Using ropes and ladders the lighthouse keepers pulled the survivors from the bottom of the cliffs to safety then cared for them at the lighthouse station for a further ten days until they could be evacuated.

The lighthouse underwent conversion to automatic operation in July 1978 but remained staffed until 1996 when the last lighthouse keeper departed making Cape Naturaliste the last manned lighthouse on mainland Australia and marking the end of an era.

Today the three original keepers’ quarters still stand, with one serving as the Lightkeepers’ Museum. The lighthouse itself still uses its original first-order Fresnel lens, now driven by an electric motor. The light characteristic displays two flashes every ten seconds, visible for 19 nautical miles, continuing its vital work guiding ships along this dangerous coastline. The white limestone tower stands as testament to Western Australia’s maritime heritage and the enduring human need to bring light to darkness and safety to dangerous waters.

Technical Summary

First Exhibited: 1904

Status: Active (Automated, unmanned since 1996)

Location: Cape Naturaliste Road, Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park, Western Australia (approximately 27 kilometres from Busselton, 267 kilometres south of Perth)

Historical Significance: Last manned lighthouse on mainland Australia; site of French exploration and naming by Baudin expedition 1801; built using locally quarried limestone

Construction Cost: £4,800

Construction Period: Ten months during 1903

Construction Material: Local limestone quarried from nearby Bunker Bay

Tower Height: 20 metres

Focal Height: 123 metres above sea level

Lantern House: 14-foot diameter, manufactured by Chance Brothers, Birmingham, England

Optical System: First-order Fresnel lens (Chance Brothers), lead crystal

Lens Weight: 12.5 tons (including turntable)

Mercury Bath: 156.5 kilograms of mercury in hollow turntable

Original Power: 755,000 candelas (incandescent vaporized kerosene lamp)

Upgraded Power: 1,213,000 candelas (1924)

Current Power: Electric illumination with mains electricity and battery backup

Visibility: 19 nautical miles (nominal range)

Characteristic: Two flashes every 10 seconds (Fl(2) 10s)

Automation: Converted to automatic operation July 1978; last keeper departed 1996

Management: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Indigenous Heritage: Traditional lands of the Wadandi people (40,000+ years of occupation)

French Exploration: Named by Nicolas Baudin expedition 1801 (corvette Naturaliste)

Keepers’ Quarters: Three original stone cottages (1904), still standing

Reserve Size: 8 hectares, abutting Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park

Notable Historic Events:

- 1907: Fireball strike during severe electrical storm

- 1907: Rescue of 14 survivors from Carnarvon Castle

- Loss of mercury shipment overboard at Quindalup jetty during construction